Once upon a time…

Forget facts. If you really want to win an argument, sell someone something or win an election, make sure you’ve got a really good story. Because humans love stories.

Once upon a time, on Columbus Day, Monday 10 October 1983, President Ronald Reagan watched a tape of a new TV movie, The Day After, showing the aftermath of a nuclear war with Russia in the town of Lawrence, Kansas. “It’s very effective & left me greatly depressed,” he wrote in his diary. “So far they haven’t sold any of the 25 spot ads scheduled & I can see why. Whether it will be of help to the ‘anti nukes’ or not, I cant [sic] say. My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war.”

Of course, this wasn’t the only reason why Reagan became less hawkish about nuclear weapons, moving towards an agreement with the Soviet Union. “But one factor was watching The Day After and being enormously moved and depressed and upset by it,” says Dorian Lynskey (Downing 1992), podcaster, journalist and author of the upcoming Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About The End of the World. “It was the most watched TV movie in American history. Countless articles were being written about nuclear war. But the film – the story – was the thing that reached people.”

Not all stories save the world. But it’s hard to imagine a world without them. Storytelling is intrinsic in what it means to be human, says Elias Garcia-Pelegrin (St Edmund’s 2019), assistant professor in comparative cognition and evolutionary psychology at the National University of Singapore. “We are the way we are because we tell stories to each other. That’s the uniqueness of humanity. I can make you understand what it is to be me, and you can make me understand what it is to be you.”

Appropriately, the origins of storytelling are lost in mystery. “Take everything I’m going to say with a pinch of salt!” says Garcia- Pelegrin. Trying to work out how our ancestors thought is far harder even than working out what they ate or wore, he points out. But we see communication in its most simple form in the animal world: birds use alarm calls to warn others about nearby predators. Perhaps humans were able to put those simple semantics into a coherent space: a narrative. That calls upon something which almost no other species does: mental time travel. “This is our ability to access our episodic memory and travel back and forth between time and space,” says Garcia-Pelegrin. “We could tell a story not about a predator that is threatening us now, but one which threatened us yesterday, or might threaten us in the future.”

When we evolved extreme cognitive complexity to navigate between the past, the present and the future – that’s when storytelling became intrinsic

We are not the only animals that do this: chimpanzees can do it, and, incredibly, some crows. “But, as far as we know, no animal does it better than us,” says Garcia-Pelegrin. “In my opinion, when we evolved this extreme cognitive complexity to navigate between the past, the present and the future – that’s when storytelling became intrinsic within humankind. And the fact that we can do it better than anything else gave us an evolutionary advantage. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have it.”

One might ask, for example, why on earth we love a story about the end of our own existence. Multiple reasons, says Lynskey. “Part of it is inhabiting your worst fears and turning them into entertainment. Largely, in most end of the world stories, the world doesn’t quite end, and people survive.”

It can be a way of appreciating real life: in Emily St. John Mandel’s post-apocalyptic novel Station Eleven, Lynskey points out, a functioning airport, “which is normally a boring, annoying place to be” is reinterpreted as a taken-for-granted miracle. “But there also more misanthropic, or even nihilistic, writers who like to say how awful things are and imagine how good it would be if that was all swept away, either in the classically apocalyptic sense of the Book of Revelation, in which the decadent old world is replaced by eternal Paradise, or with the opportunity for a bizarre new life that you make for yourself, which is a feature of JG Ballard novels.”

These tropes would have been all too familiar to Reagan himself: the power of a good narrative was central to his success – and the success of many of his peers. “Storytelling is absolutely central to what politics is,” says Dennis Grube, Professor of Politics and Public Policy. “Democratic politics, especially, is ultimately the art of persuasion – we need to bring people with us. The goal for politicians, I say, is to tell a story in a way that successfully persuades voters that the government is acting in their best interest, on their behalf, to tackle an issue in a way that works. That’s more than regaling people with a list of facts, because facts don’t speak for themselves. Facts need to be interpreted and placed in an order that makes sense.”

Today’s voters may well be more cynical than those who were exposed to Reagan’s folksy anecdotes, but we are still likely to respond to stories that connect with our broader worldview. Grube cites the image of former Prime Minister Boris Johnson driving a JCB digger with ‘GET BREXIT DONE’ emblazoned on the bucket through a polystyrene brick wall, festooned with the word ‘GRIDLOCK’. “On Thursday [election day], I think it is time for the whole country, symbolically, to get in the cab of a JCB – a custard colossus – and remove the current blockage that we have in our parliamentary system,” Johnson announced afterwards. The country duly obliged. “He’s telling a story there,” says Grube. “It’s honestly the simplest story you or I could conceive of. And for that moment, it does the job that it needs to do. It persuades voters that he is the person to drive through this metaphorical wall. It’s effective.”

Societies need a rigorous understanding of how stories work, and what effects they can have

And as stories are ever-present and hugely powerful, we should take them more seriously, says Sarah Dillon, Professor of Literature and the Public Humanities, and co-author with Claire Craig (St John’s 1979) of Storylistening: Narrative Evidence and Public Reasoning. Rather than shutting down English and creative writing departments and pushing STEM subjects to the exclusion of all else, she argues, societies need a rigorous understanding of how stories work, and what effects they can have.

“There is often a desire to dismiss stories, because from a scientific perspective, they are perceived to lack rigour or be overly seductive or persuasive,” she says. “The suggestion is that they are dangerous, in a certain way, because you can’t control them and categorise them the way you can with other forms of evidence. But our argument is that you can’t get away from stories. We are, as narrative theorist Walter Fisher says, Homo narrans. We are human beings defined by the stories that we tell and consume.”

Dillon and Craig’s Storylistening Framework provides a way for policymakers to use stories to gain insight into today’s wicked problems, like climate change, or unknown quantities such as AI bias. How might it work? Dillon cites the work of Joseph Weizenbaum, who created the first natural language processing software at MIT in the 60s. He named it ELIZA, after Eliza Doolittle in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion.

“He called it that because it could be taught,” says Dillon. “George Bernard Shaw was an advocate of feminism. Pygmalion is a very interesting feminist text. What was Weizenbaum thinking when he chose Eliza as the name? What did he not learn from the text that he took the name from? That might have been helpful in informing and developing his thought and his practice in perhaps more equitable and just ways.” (ELIZA is still very much alive, incidentally: last year she beat OpenAI’s GPT-3.5 in a Turing test study.)

Using stories in this way, Dillon says, helps us understand those parts of the world that can’t only be understood by science. And stories themselves are a part of that world – like rocks or gravity. “Therefore, they deserve to be studied and understood, just like the physical parts of the world. They are a tool and a method for making sense of elements that we find difficult to make sense of in other ways – that involve complex interactions across multiple scales, that involve people and emotions, and all those things that social sciences find it hard to quantify.” Take the recent storm whipped up by the ITV drama Mr Bates vs The Post Office, which brought a vast and complex story of institutional failure – which had previously gone under most people’s radar – to the attention of a horrified nation. We have yet to see the full consequences of the fury this story unleashed. But they could be huge: for victims, for perpetrators, for governments.

The suggestion is stories are dangerous because you can’t control or categorise them the way you can with other forms of evidence

And while, for most of us, stories will have personal not political ramifications, that makes them no less powerful. Yvonne Battle-Felton, Associate Teaching Professor and Academic Director of Creative Writing at Cambridge University Institute of Continuing Education, tells the story of her grandfather. “He longed to be a musician and dreamed of going on the road. His family needed a steady income so he took to teaching the piano. He never fulfilled his dream.” But Battle-Felton fulfilled hers. “From his story, I’m reminded of what it’s like to have a dream and never being able to pursue it – and the importance of following those dreams and making sure that my children get to see me do it.”

When Battle-Felton started a true story open mic night, encouraging people to come and tell a story about themselves, she was startled by those who thought they didn’t have a single story to tell. “Because they hadn’t climbed a mountain, or done something that other people thought was important, they didn’t think they had a right to tell their story. And that still saddens me. We need to be able to tell our own story and write our own story. It’s a powerful thing, being able to write where you see absence. If you don’t see yourself reflected, then it’s easy to tell yourself there are certain things you can’t do.”

Lose stories, she says, and we lose our future. “We can’t allow that. Those in power read, watch movies, go to theatres. But they don’t think other people deserve to. We need to write another ending into existence, where stories are valued. If we do that, more and more people will be able to imagine that ending, visualise it and achieve it.”

-

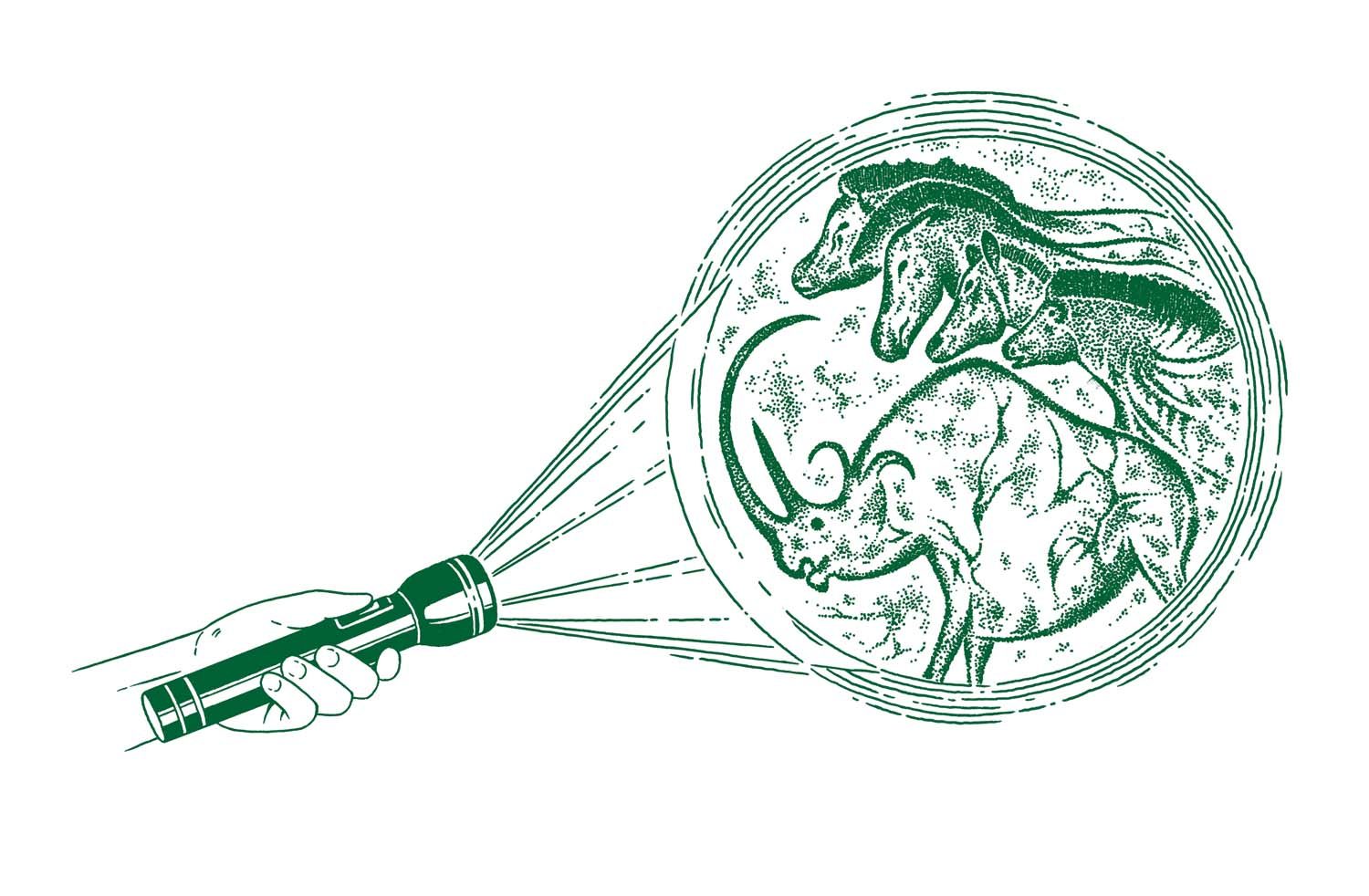

The Chauvet cave paintings

30,000–32,000 bce

Discovered on 18 December 1994 by three speleologists, the walls of the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in France are covered with extraordinary animal paintings: mammoths, cave hyenas, ibex – and even rhinoceroses. A child’s footprints pattern the floor. One drawing appears to be an erupting volcano: the earliest known depiction of this event. “This is the birth of the modern human soul,” said film director Werner Herzog, who filmed the paintings for his 2010 documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams.

-

The bright star Moinee

10,000 bce

Palawa (Tasmanian Aboriginal) stories relating the creation of the Bass Strait, 12,000 years ago, recall Moinee being a bright star near the South Celestial Pole at the time rising seas made Tasmania an island. Recent research from the University of Tasmania has shown that this is an accurate description of the sky and the star Canopus as it would have appeared 11,960 years ago. That means these oral traditions have been passed down through more than 400 successive generations. (There may be stories far older: Indigenous Australian culture stretches back around 50,000 years.)

-

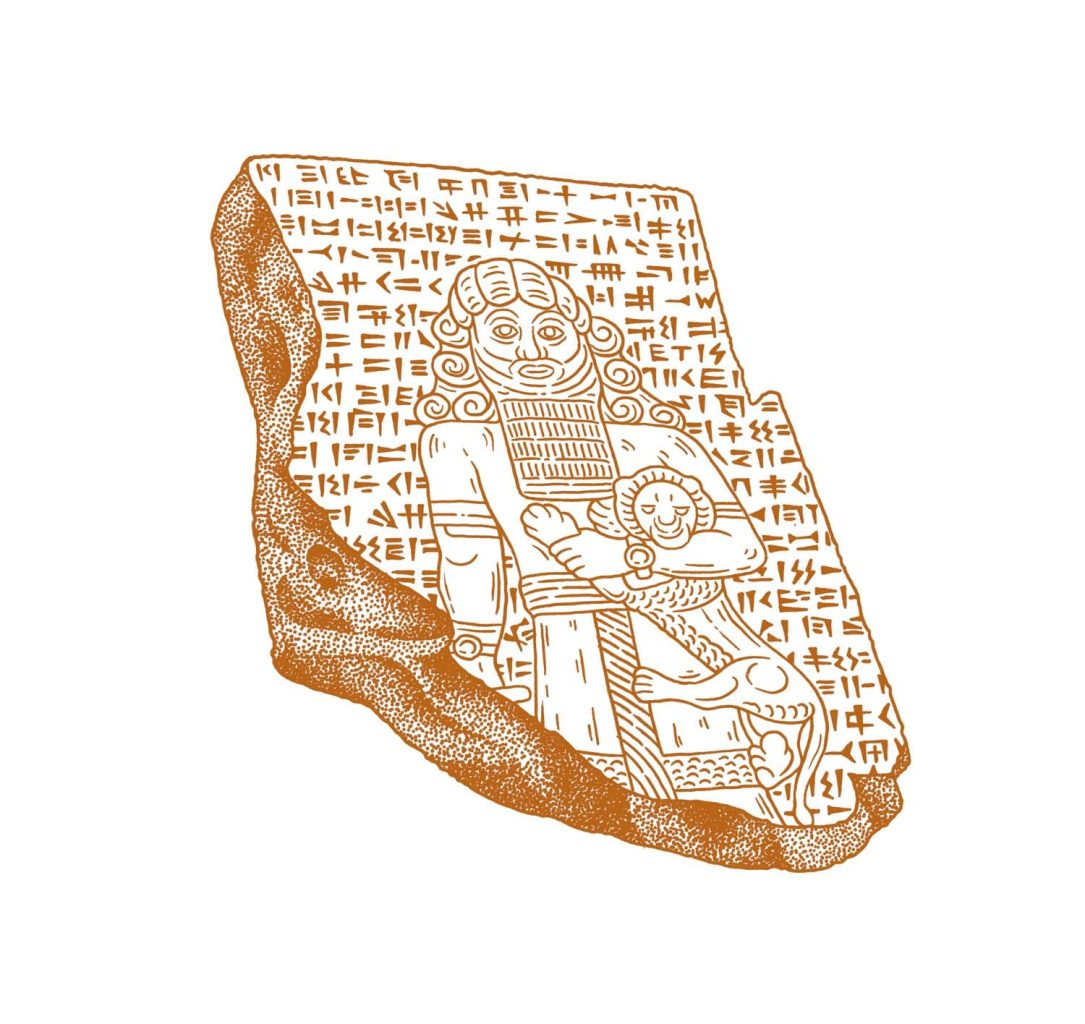

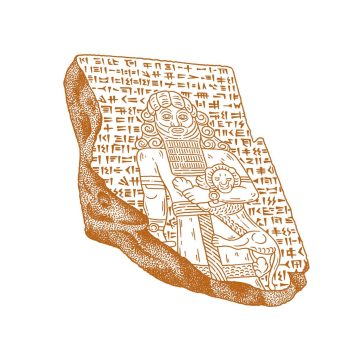

Gilgamesh

2700 bce

“Supreme over other kings, lordly in appearance, he is the hero, born of Uruk, the goring wild bull.” Meet Gilgamesh, king of the Sumerian city state of Uruk and hero of the oldest written story yet known, written in the ancient language of Akkadian on 15,000 fragments of clay tablets in cuneiform script. First translated by self-taught Assyriologist George Smith in 1872 – who, the legend goes, was so excited by his discovery that he ran around the room removing his clothes – it contains an account of a great flood written a thousand years before the biblical story of Noah.

-

The odyssey

700–800 bce

“Tell me, O Muse, of the man of many devices, who wandered full many ways after he had sacked the sacred citadel of Troy.” The Odyssey is one of the oldest stories still read by modern audiences, but this ancient Greek poem attributed to Homer has also been reimagined countless times across the centuries, from James Joyce’s Ulysses to the Coen brothers’ Deep South-set crime comedy O Brother, Where Art Thou? A 2018 BBC poll voted it literature’s most enduring narrative.

-

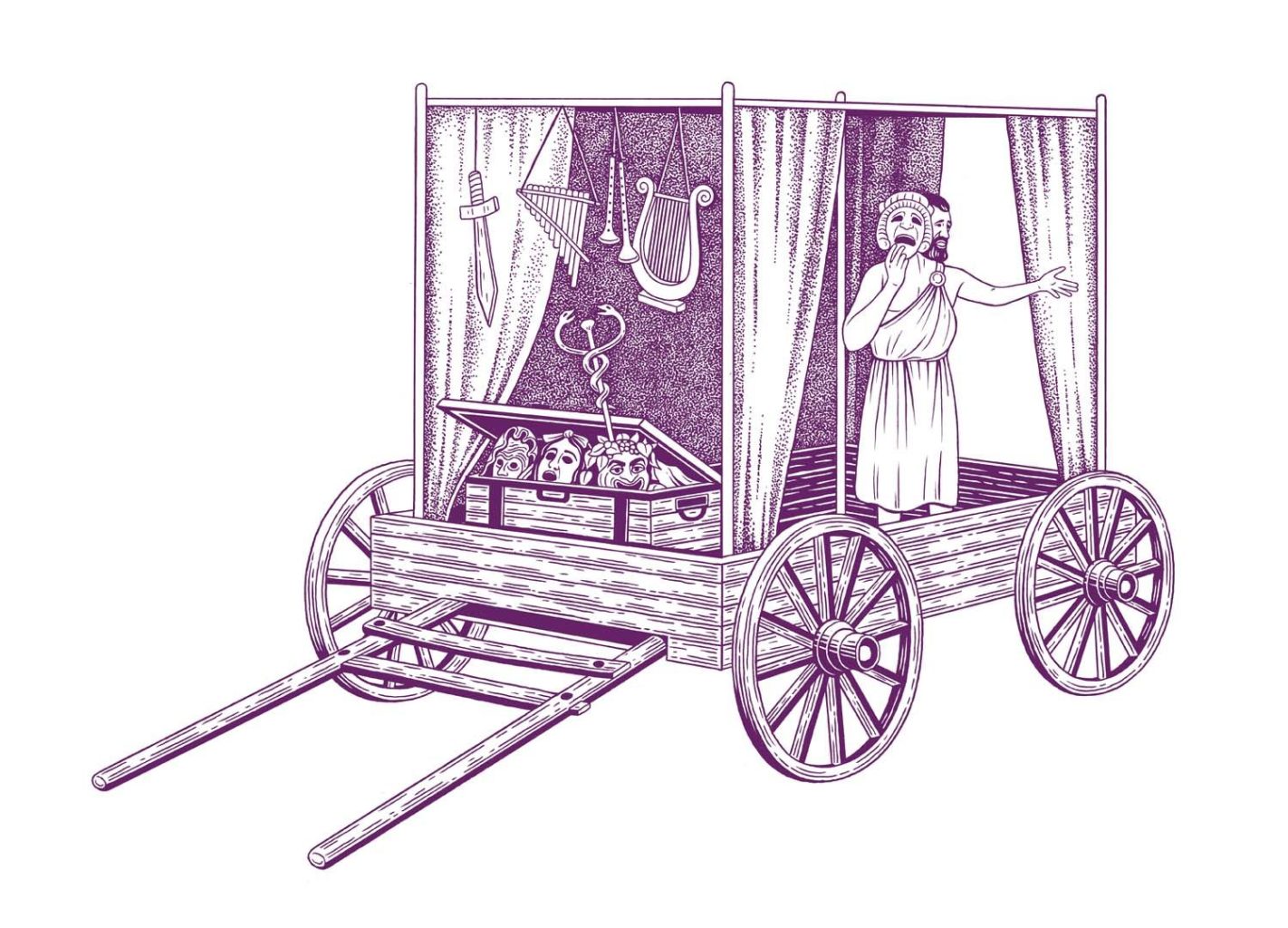

Thespis

500 bce

Thespis was not only the first person to appear on stage playing a character, he also invented the stage (a wooden cart) and the theatrical tour: taking said cart, filled with costumes, masks and props, to cities in Ancient Greece. His innovative style – performing individual characters in the same story, using masks – became known as tragedy. It has also caught on.

-

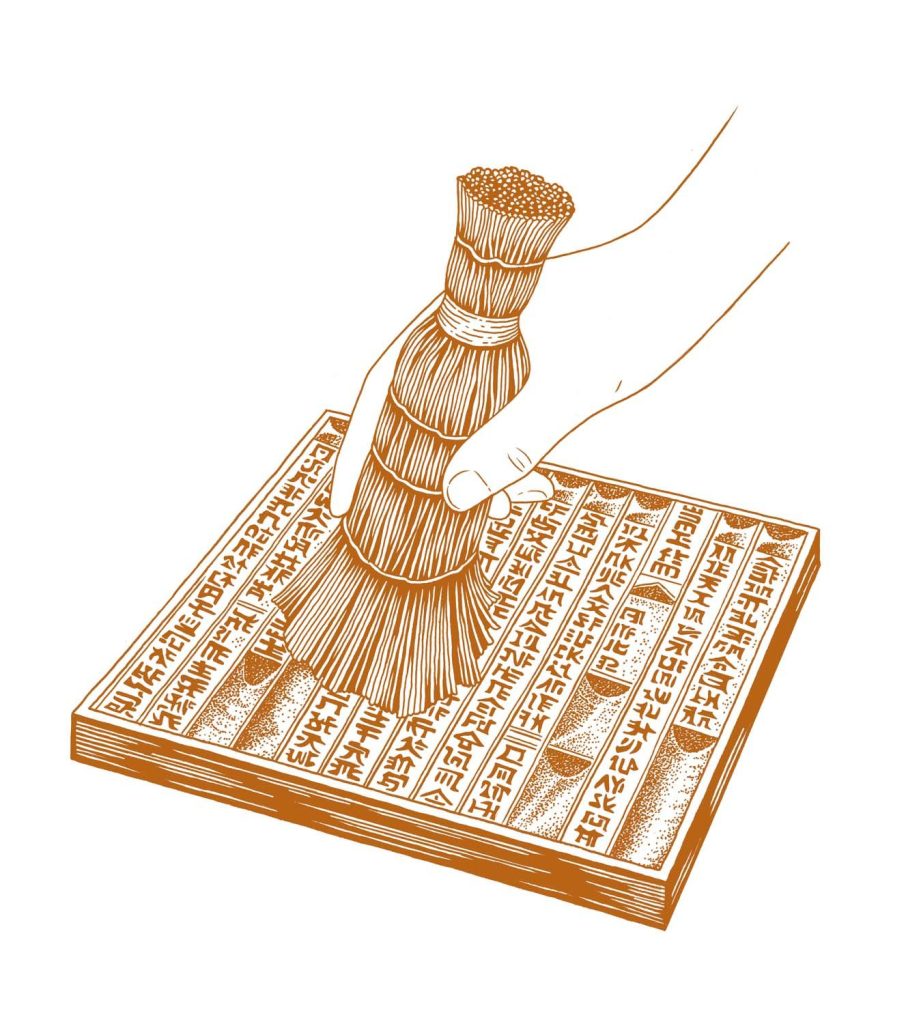

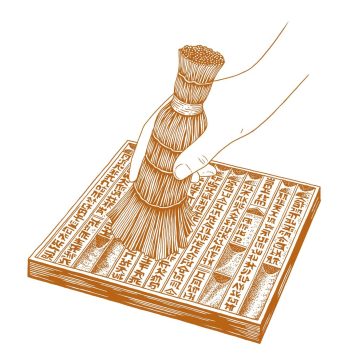

The Diamond Sutra

868 ce

In 1900, a Chinese monk cleaning sand in a meditation cave discovered a chamber filled with scrolls, untouched for 900 years. Among them was the world’s oldest printed book – The Diamond Sutra – was found: a 16 foot-long scroll, printed by woodblock on paper, with an illustrated cover depicting the Buddha. Along with the Buddha’s discourse, it also contains the first known example of open copyright: “Reverently made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 15th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong [11 May 868 ce].”

-

The tale of Genji

1008 ce

Legend has it that Murusaki Shiki, novelist, poet and lady in attendance at the imperial Japanese court, was inspired to write what is considered to be the world’s first novel, at the temple of Ishiyama-dera, while staring up at the August moon. Ian Buruma, writing in the New Yorker, sums up her millennia-long appeal: “the keen, sometimes sardonic, and always worldly eyes of a medieval Jane Austen”.

-

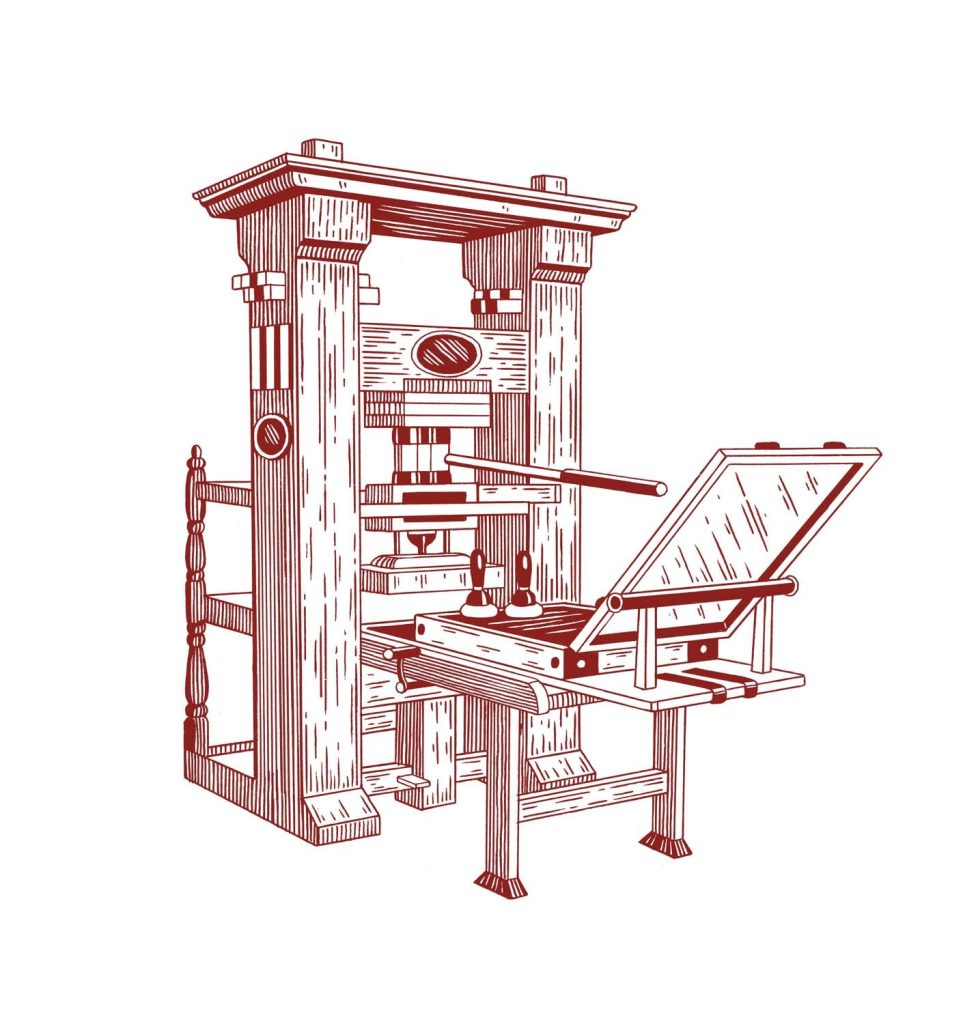

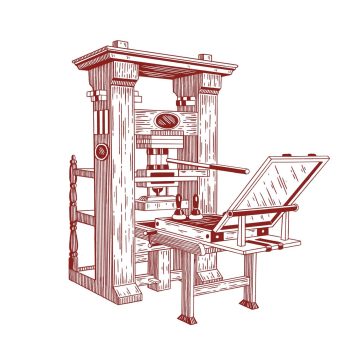

The 42-line bible

1454 ce

So-called as every page contains 42 lines of text, this was the first book printed in Europe on the moveable type printing press invented by Johannes Gutenberg, who has since been named one of the most influential figures of all time. It was an immediate sellout at the bargain price of 30 florins – around three years’ salary for the average clerk. Guterberg’s achievements were recognised in his lifetime by Archbishop von Nassau, who granted him a stipend, an annual court outfit, 2,180 litres of grain and 2,000 litres of tax-free wine.

-

La fée aux choux

1896 ce

The Fairy of the Cabbages is arguably the earliest film to tell a story – and the first to be directed and edited by a woman, Alice Guy. For those weary of three-hour epics, it is a commendable 60 seconds long, and involves a couple on honeymoon, a farmer, some cardboard cut-outs of babies, an actual baby, and many cabbages.

-

The war of the worlds

1938 ce

“I had conceived the idea of doing a radio broadcast in such a manner that a crisis would actually seem to be happening and would be broadcast in such a dramatised form as to appear to be a real event taking place at that time, rather than a mere radio play.” Orson Welles’ radio adaptation of the HG Wells novel continues to intrigue: was it ‘fake news’? Was the mass panic it supposedly sparked a media-created myth? Was it, as Vanity Fair claimed, “history’s first viral media phenomenon”?

-

Faraway Hill

1946 ce

Soap operas had long been popular on radio, but Faraway Hill was the first to televise this new form of storytelling. Delving into the life and loves of wealthy New York City socialite Karen St. John, it featured an ‘all-seeing voice’ to advise the characters, which sadly never caught on. “Turn back, turn back, Karen St. John! Something inside you is sounding a warning – this is no place for you… How can you stay?”

-

Colossal Cave Adventure

2014 ce

At just 700 lines of code and 700 lines of data (including descriptions for 66 rooms, navigational messages, 193 vocabulary words and miscellaneous messages), Colossal Cave Adventure could be considered one of the shortest groundbreaking texts ever created. This simple text-based computer game, created by programmer and keen caver William Crowther for his daughters, is the one of the first interactive fiction games, and the first which allowed a player to explore a virtual world – albeit through one- or two-word commands only. (The actual Colossal Cave is real: it’s in Kentucky, but sadly, unlike the game, has no dragon.)

-

Serial

2014 ce

Downloaded an estimated 300 million times, Serial – hosted and created by journalist Sarah Koenig – was the first podcast to go viral. The first and most famous season investigated the killing of 18-year-old Hae Min Lee and subsequent conviction and life sentencing of Adnan Syed, her ex-boyfriend. In 2022, his conviction was overturned and he was freed.

-

chat generative pre-trained transformer

2023 ce

By January 2023, ChatGPT had become the fastest-growing consumer software application in history, gaining more than 100 million users. How the ability for authors to write with the help of AI will change storytelling remains to be seen – though it must be said that no Austens, Joyces or Shakespeares have yet emerged. In July 2023, the Independent reported that Amazon was being “flooded” with AI-generated books, including such titles as ChatGPT smarter than humans?, Make more money with ChatGPT, and The star weaver’s lesson: Magical bedtime story.