The ridiculous to the sublime

Why does satire exist? Why has it been such an important tool for challenging public discourse? And in a world which sometimes seems beyond satire, does it still have the same power today?

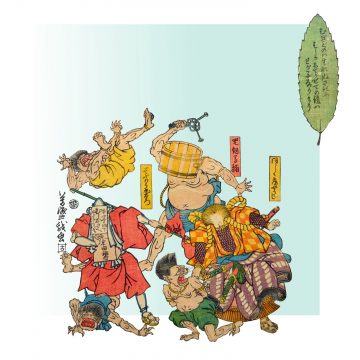

It is 1963 and the young Professor Vic Gatrell, now a Life Fellow of Caius and author of the Wolfson Prize-winning City of Laughter, has arrived in just-about-to-start-swinging London from apartheid-era South Africa, where his liberalism and that of his parents is taboo. One day, he picks up a copy of irreverent magazine Private Eye, opens it, and sees the now-notorious Gerald Scarfe cartoon of a doe-eyed Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, naked and coy, astride an Arne Jacobsen chair in a parody of Christine Keeler’s iconic pose. “I had never seen anything like it before,” he recalls. “I laughed and laughed. And that image opened the floodgates.”

It could be argued that, like Philip Larkin’s sexual intercourse, modern satire also began in 1963, and quite a lot of it came from Cambridge: Peter Cook (Pembroke 1957), Beyond the Fringe, That Was The Week That Was and so on. “It wasn’t until the 1960s that a non-deferential attitude to people in charge really started,” says Jan Ravens (Homerton 1978), first female president of Footlights and legendary impressionist whose voices have graced groundbreaking satirical puppet show Spitting Image and hit BBC radio and TV show Dead Ringers. “Before then, there was an unwritten, unspoken agreement – that you didn’t take the piss out of politicians.”

But 1960s satire, of course, was nothing new. Rather, it was a continuation of a tradition stretching back to antiquity. In fact, one anti-authority Cambridge graduate may have preceded Cook et al by about five hundred years.

Satire is comedy’s shapeshifter; it takes on whatever form society requires… The world is changing so rapidly that satire is enjoying a kind of heyday, a way of reflecting on the chaos of the grand narrative

Meet orthodox priest and late-15th-century Cambridge graduate John Skelton, who imitates and alludes to the traditions of classical satirists such as Juvenal in his satires, aimed not at the Roman despots but the low-born Cardinal Wolsey. According to Dr Dan Sperrin, junior research fellow at Trinity and cartoonist for The London Magazine, who is working on a complete history of satire: “Wolsey makes his way to high political office and once he has achieved that, he achieves high clerical office. And Skelton is not happy, asking ‘Who is this guy? What is this world where upstarts can claim any power they want?’”

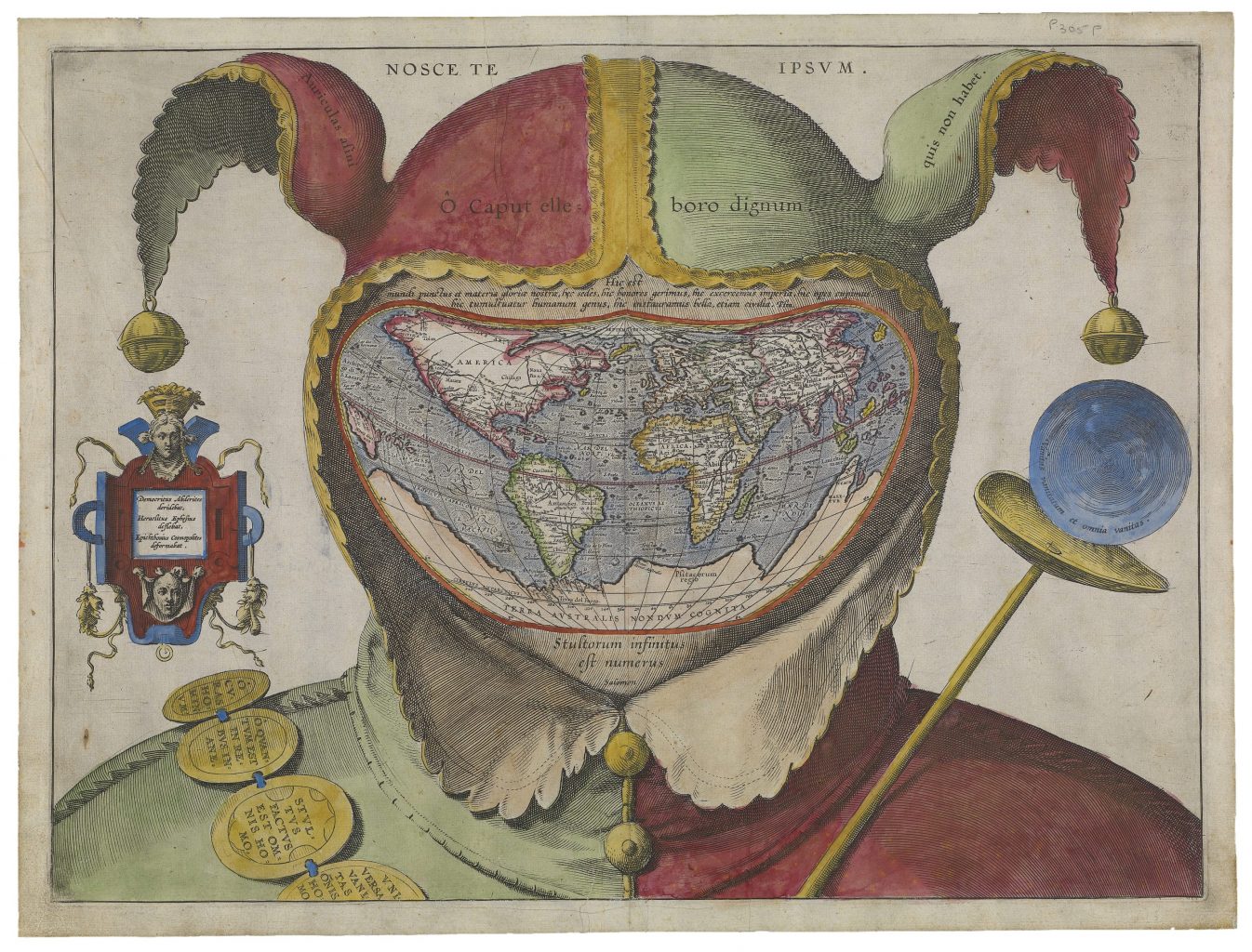

Fool’s cap map of the world, 1580–1590

This satirical print, believed to be the work of Epicthonius Cosmopolites and based on Ortelius’s third ‘Typus Orbis Terrarum’, ridicules the imperial ambitions of the great maritime nations. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

“This is world, and this is the substance of our glory, this is its seat, here it is that we fill positions of power and covet wealth, and throw mankind into an uproar, and launch wars, even civil ones.” Text above the map from the Latin, quoted from Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (bk. 2 ch. 72)

“The number of fools is infinite.” Text below the map from the Latin, from Ecclesiastes, 1.15

An orthodox priest taking a pop at a cardinal for being the son of a butcher might not seem particularly cutting-edge to today’s satirists. But satire, says Sperrin, is comedy’s shapeshifter: it takes on whatever form that society requires. “We’ve become used to the idea that satire is one thing, when in fact there have been innumerable models of satire that have served different political agendas at different times.”

Take hard-hitting forms of visual satire, like Scarfe’s cartoon, which tend to follow certain conventions, says Dr Meredith Hale, Speelman Fellow at Wolfson College from 2009 to 2018 and currently lecturer in art history and visual culture at the University of Exeter. “Visual satire tends to be representative and figurative in nature, not abstract,” she says. “It also suspends the action: you often find yourself as a viewer entering the action as it’s taking place. Rarely do we have a narrative with an arc from beginning to end or see something to its conclusion. That’s primarily to keep it from being defined as either tragedy or comedy but also to let the viewer finish the narrative. But that visual chaos is key.”

The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, 1605–1615

Miguel de Cervantes’ chivalric satire demonstrates the hypocrisy of the knight-errant. This engraving by Jacques Chéreau, accompanying an edition of 1690, entitled Adventure in the enchanted boat, depicts the titular Don Quixote standing in a boat and attacking a watermill he has mistaken for a fortress. On the left, two millers in a boat are trying to keep him away from the mill’s wheel. The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

“You are to know, Sancho, that this vessel lies here for no other reason in the world but to invite me to embark in it.” The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha

Satire is also deeply implicated in a specific historical moment: it doesn’t travel well, geographically or temporally. “I show my students a Steve Bell cartoon from 2004 featuring George Bush in a little onesie, with his very particular monkey-like physiognomy, and Tony Blair as his little lapdog with a British flag sticking out of his backside,” says Hale. “They are watching a screen with weapons inspectors wearing Teletubby outfits. One of them is saying: ‘Chemitubby can’t find weapons of mass destruction.’ And my students have no idea what it could be about. There’s a huge amount of context required to unpack satire: it’s dense with history, nuance, political and cultural references.”

Rakewell coldly discards his pregnant, lower-class fiancé Sarah Young, even as he is measured for a new suit.

Ⅲ The Orgy

Rakewell is too intoxicated to notice that his pocket watch is being stolen by prostitutes at the Rose Tavern in Covent Garden.

Ⅵ The Gaming House

Rakewell has gambled away a second fortune – acquired through his marriage to Sarah Young – in a scene redolent of folly, avarice, greed and despair.

Ⅷ The Madhouse

After losing multiple fortunes and enduring Debtor’s prison, Rakewell lies naked and insane in Bedlam as a grieving Sarah Young mourns.

The Rake’s Progress, 1732–1734

This narrative series by William Hogarth mocks the excesses of Georgian society and warns of the consequences of moral abandonment.

Its protagonist, the fictional Tom Rakewell, inherits a fortune from his miserly father, but squanders it, following a path to vice and destruction. Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

However, Tyler Shores, manager of the University’s ThinkLab Program, cites one of the most successful satires of all time – the animated series The Simpsons – as about as close satire can get to evergreen. (Indeed, he devised an entire course on it at Berkeley: The Simpsons and Philosophy, and recently hosted a talk by Harry Shearer, legendary satirist and voice of Montgomery Burns among others, at Jesus.)

We’ve become used to the idea that satire is one thing, when in fact there have been innumerable models of satire that have served different political agendas at different times

For those seeking the perfect example, he suggests a close watch of season 2, episode 4, Two Cars in Every Garage and Three Eyes on Every Fish. (The episode title itself satirises an advertisement for Herbert Hoover’s 1928 presidential campaign: A Chicken in Every Pot!). When Bart catches a three-eyed fish, inspectors order evil capitalist Montgomery Burns to fix his nuclear power plant. Burns decides to run for governor, so he can pass laws to bypass costly regulation and keep the plant open. To this end, he hires an actor dressed as Charles Darwin to explain why three-eyed fish are a Good Thing. “Every now and then, Mother Nature experiments with her creatures, giving them longer legs, sharper claws or, in this case, a third eye. If she finds the changes favourable, the creatures will multiply and a new race of superfish will be created,” the actor explains. “It’s one hundred per cent applicable to 2022,” says Shores. “It’s got crooked billionaires, political division and even fake news.” To further quote The Simpsons: it’s funny because it’s true.

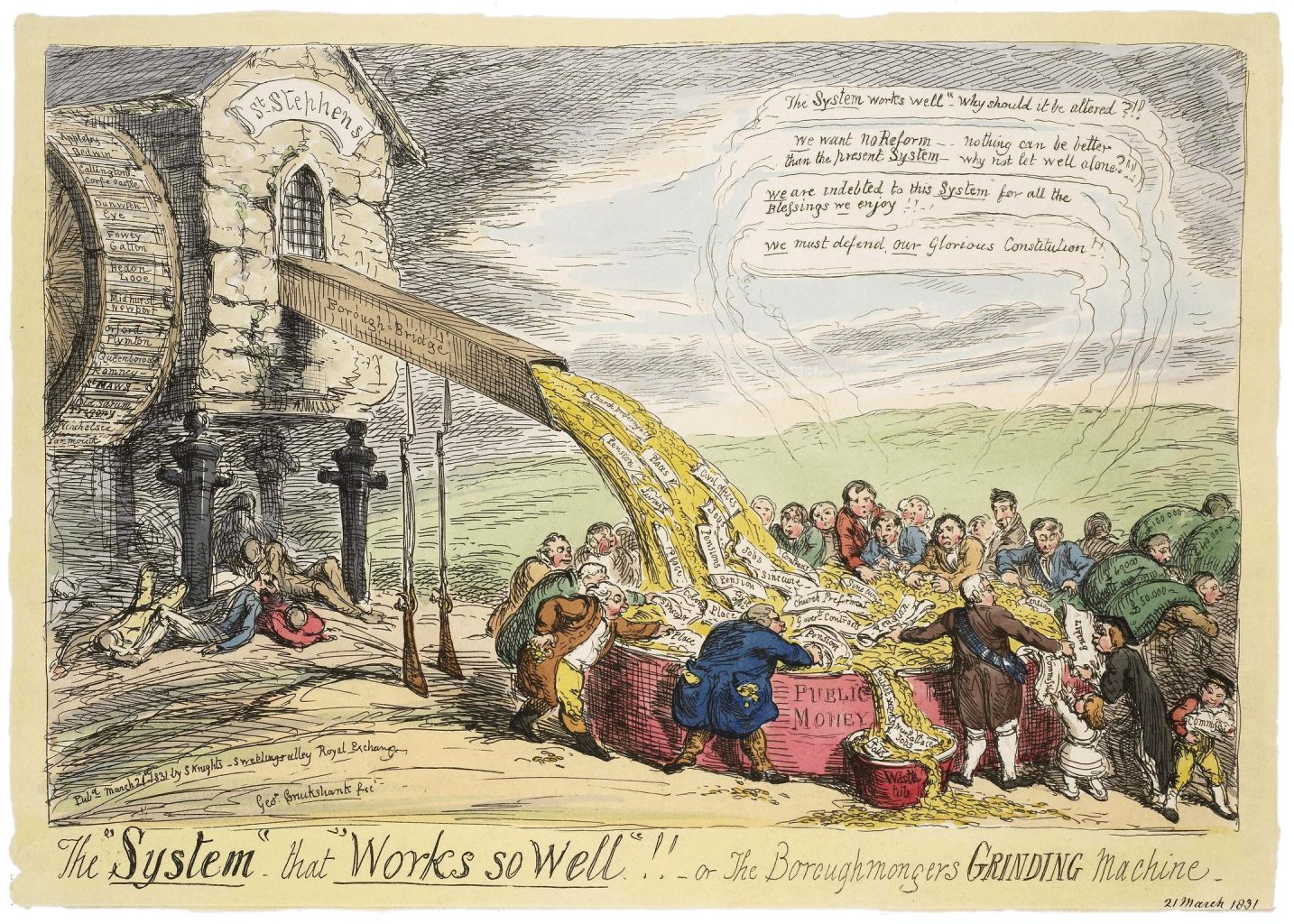

The “System” that “Works so Well”!!, 1831

This print by George Cruikshank is a bitter satire on the defenders of the borough system. The House of Commons is shown as a decaying mill, powered by the names of boroughs to be disfranchised, and supported by cannon – indicating military power for civil coercion – beside which lie the bodies of victims of ‘the System’. Across ‘Borough-Bridge’ pours a golden stream into a vat of ‘Public Money’ where a greedy crowd are filling their pockets. The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

“For me, this kind of satire holds up an honest mirror to the good and the bad of American life,” says Shores. “The importance lies in a thoughtful kind of laughter. Good satire should make us laugh, should make us think and question common assumptions about ourselves. It’s not just to get a laugh but to take a step back – we all have our blind spots, and with social media they have accelerated. We need that prompt.”

Good satire should make us laugh, should make us think and question common assumptions about ourselves. It’s not just to get a laugh but to take a step back – we all have our blind spots

We clearly do: there must be a reason why this form of humour has endured for so long. One school of thought, points out Sperrin, has satire as a conservative form of humour, one which gets in the way of active change. Harry Shearer himself says that satire could be defined as the enemy of revolution: a safety valve for anger. “The last thing a committed organiser wants to generate in a crowd is laughter: it dissipates the will to action. I have the opportunity, in my weekly radio show, to make fun of whatever I want. I took great advantage of that during the Trump years, and I noticed that I was less angry about Trump than all my friends, because I had an outlet. It’s hard to attack a building when you’re laughing.”

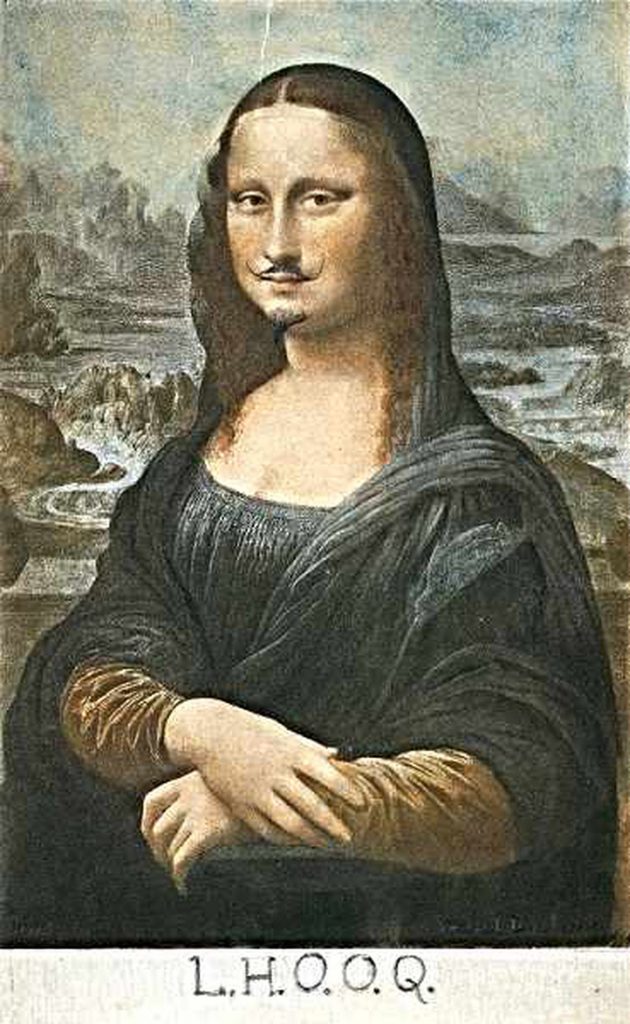

L.H.O.O.Q, 1919

One of Marcel Duchamp’s most famous ‘ready-mades’, this cheap reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa has been adorned with a comical moustache and goatee and the letters L.H.O.O.Q underneath. The letters, when said in French, translate to ‘She’s got a hot ass’, or in Duchamp’s own words, “There is fire down below”. It’s a pointed jab at the bourgeoisie and the cult of art in late 19th century that centred around the Mona Lisa, revered as the embodiment of aesthetic beauty. The work criticises the male gaze and the repression of female sexuality. It also alludes to da Vinci’s homosexuality and discusses ideas of gender non-conformity – Duchamp’s female pseudonym ‘Rrose Sélavy’ later appeared in a series of photos by Man Ray. Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2022

Ravens, too, likens satire to a safety valve. “Satire isn’t going to bring down the government or change the world. It can, to some degree, change an angle or a perception. It provides a place where we can all say, ‘We’re pissed off with these people lying to us, patronising us and treating us like we’re idiots.’” But the existence of a safety valve can mean the explosion never comes: all that fury is harmlessly expelled. Gatrell points out that there’s not a politician in Westminster who doesn’t hang a caricature of themselves in the downstairs loo. “You might ask what is the point of satire if the great and the good can survive it – or even be flattered by it? No government has been brought down, as far as I know, by satire, or by jokes at its expense.”

There’s not a politician in Westminster who doesn’t hang a caricature of themselves in the downstairs loo. You might ask what is the point of satire if the great and the good can survive it – or even be flattered by it?

Yet while satire might not change things by itself, says Hale, it can make a difference at the right moment. In late 17th-century Holland, etcher, draftsman and political cartoonist Romeyn de Hooghe found himself in the centre of a political moment. William of Orange wanted funds from Holland’s merchant elite to invade England and ensure that the country stayed Protestant. But there was a problem: the action would annoy France, a country key to successful trading. As a result the Dutch oligarchs weren’t prepared to pay up.

So, de Hooghe produced a series of satires aimed at persuading those traders who didn’t particularly like William, but were concerned about France’s Louis XIV’s military prowess and his Catholicism. “And it worked,” says Hale. “William got the money, invaded and became king. So here we see satire serving a more subtle function. You think because satire is extreme it must speak to the extreme wing of political parties. But in fact, it’s really about a subtle sort of middle ground. It’s planting a seed.”

The Thick of It, 2005–2012

Armando Iannucci satirises the inner workings of British government and the culture of spin. Apart from its profanity, the series became well known for storylines that have closely mirrored, or in some cases predicted, real-life policies, events and scandals. Des Willie / BBC Archive

“It is possible to have a good resignation, you know!”

Malcolm Tucker – The Thick of It

You think because satire is extreme it must speak to the extreme wing of political parties. But in fact, it’s really about a subtle sort of middle ground. It’s planting a seed

No era of political upheaval is complete with its proclamation of the death of satire. But Sperrin says that our so-called post-satire, truth-is-stranger-than-fiction times are, in fact, a great time to be a satirist. “Many believe we are living in a world of untrustworthy superiors, where narratives are being rewritten at a pace we can’t keep up with. The world is changing so rapidly and, to the satirist’s eye, so aimlessly, hectically and chaotically that satire is enjoying a kind of heyday. It’s become a way of reflecting on the chaos of the grand narrative. And I trust satire’s ability to provide valid, energetic and robust criticism in new forms.”

And a post-satire world assumes, says Shearer, that satire has one job: to exaggerate dramatically what we are living through. “From my point of view, that’s not its role. For me, satire’s job – and there are a million ways to do it – is to observe closely the absurdities of reality, reproduce them as accurately as possible and edit out the boring parts. And we can keep doing that forever.”