Smash The Patriarchy

2018 is going to be a big year for feminist thought and action. But what does change look like to the Cambridge women leading the charge?

The ‘fourth wave’ of feminism was first heralded by The Guardian, with journalist Kira Cochrane citing the sudden mass of “protests, marches and talks”, the popularity of Laura Bates’s (St John’s 2004) Everyday Sexism project, Caroline Criado-Perez’s campaign for female representation on British bank notes, the No More Page 3 petition, as well as the Reclaim the Night and One Billion Rising marches.

Five years on, and the visibility of feminism is greater than ever. The Huffington Post hailed 2017 ‘The year of the feminist’, calling the Women’s March “the biggest one-day protest in history”. In December, the American Merriam-Webster dictionary announced that its word of the year – based on the number of word definitions looked up on its website – was ‘feminism’. The explosion of the #MeToo hashtag, which women around the world use to write about having experienced sexual assault and harassment, continues to receive widespread media coverage.

A space has opened up in which new questions can be asked, rule books can be ripped up and entrenched behaviours challenged. But what does it mean to the young women who are leading the charge? Do they see the new feminism as clearly defined? And where do they think feminism is going?

“Modern feminism is what ‘feminism’ at its core has always been about: striving for equal rights for all people, regardless of gender,” says Heenali Patel (King’s 2008), communications officer for the Fawcett Society and founder of the 1000 Women initiative, focusing on the mental and sexual health challenges faced by minority ethnic women. “Being a modern feminist involves campaigning to change the law for a fairer society; challenging sexist attitudes and gender stereotypes; and showing solidarity with others who fight for the rights of oppressed groups.”

“Brexit as is one of the biggest challenges to the rights of women in the UK. So much of our equality law is written into EU legislation.”

Heenali Patel

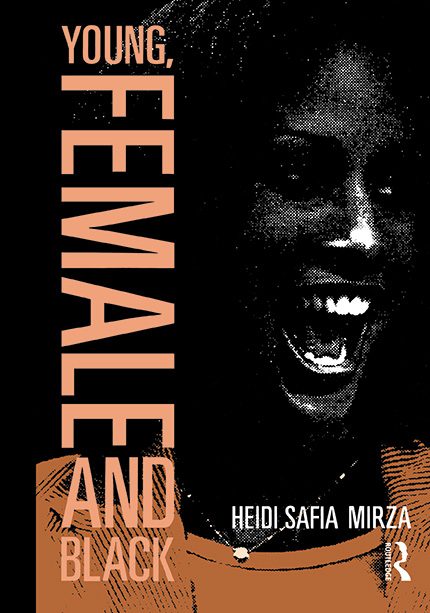

CUSU Women’s Officer, Lola Olufemi (Selwyn 2014), coordinates the work of the University’s Women’s Campaign, and points out that feminism today is about more than how any given culture defines what a feminist, or feminism, should look like. “I call myself a feminist, a black feminist,” she says.

“It means I believe in the ultimate goal of liberation for everybody. I think feminism allows people to imagine liberatory futures and goes well beyond the concept of ‘equality’. Feminism is justice work. But it’s entirely dependent on context and the way gender is perceived where you are; its social and political meanings.”

That intersectionality – taking into account human factors such as ethnicity, sexuality and economic background – is vital to understanding feminism in 2018. Jinan Younis (Jesus 2013) is assistant politics editor at gal-dem – a magazine for women and non-binary people of colour – and was part of a team that successfully lobbied for sexual consent workshops that are still being run by student unions today. Younis came to the attention of the media at the age of 17 when she set up a feminist society at her high school (shockingly, it took more than a year for the school to officially approve the society), and says that creating a more inclusive, more diverse type of feminism is vital.

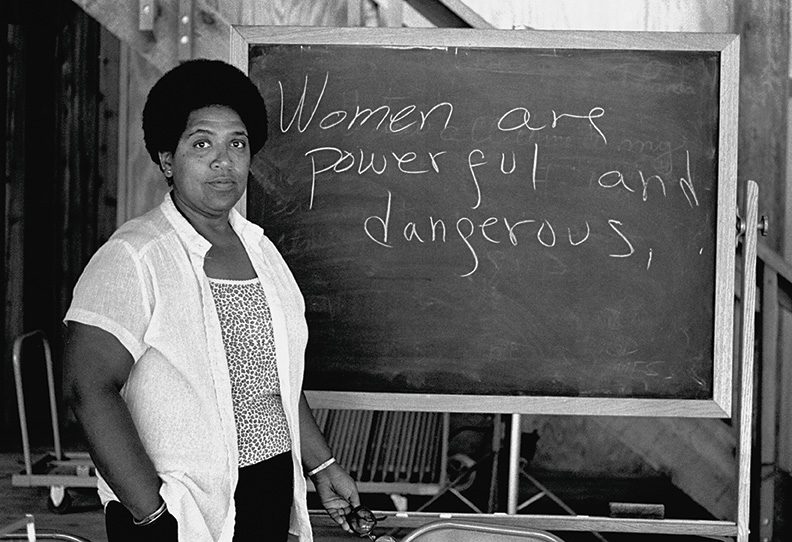

“I think the future of feminism has to be intersectional,” she says. “We need to actively work really hard to make sure we are as inclusive as a movement and that we’re not leaving anyone behind. It’s like Audre Lorde famously said: ‘I am not free while any woman is unfree, even when her shackles are very different from my own.’”

Male feminism

Many people consider the chief defining characteristic of feminism today to be its expression via social media and the internet, both of which provide effective platforms for the dissemination of ideas and campaigns. Historian Dr Lucy Delap agrees that, while the DIY ethos of activism has always been a hallmark of feminism, the accessibility of the movement – as a result of the internet – is new. “What’s so powerful about both Everyday Sexism and the #MeToo campaign is the sense of authentic voices,” she says. “It’s all about women saying, ‘This is my experience’ – and that has been radically democratic. It’s really given a boost to the profile and audibility of feminism.

She adds that the role that men are being encouraged to play might also be new. “It’s never been very easy for men to say, ‘Yes I’m a feminist’. But I do think that that has changed.” Delap believes that self-proclaimed feminist Barack Obama, for example, is a hugely important “feminist icon”. She adds, “You go to today’s feminist conferences and you see lots and lots of men there. Twenty-first century feminism is more comfortable about men’s presence.”

“The #MeToo movement has definitely ramped up the pressure on institutions that have, at best, turned a blind eye to sexual harassment.”

Younis believes the rise of social media in feminism is especially important for more marginalised groups. “Social media can be a place that’s deeply accessible,” she says. “It provides a space for people to meet, connect and join forces with others across the world. It helps people feel less isolated in their experiences. But the dark undertone of social media must also be recognised, as it opens up another space for women to be attacked.”

Olufemi also thinks social media has been a crucial tool. “It allows people to reframe feminist thought,” she says. “Mainstream feminism insists that it was the suffragettes who invented feminism and that it has moved forward along straight lines. Social media allows us to learn about the stories of people who have been written out of feminist narrative because of their radical work, be they women of colour, trans, queer or disabled.”

And it’s certainly true that social media has given feminist voices a powerful scale and reach. “The #MeToo movement has definitely ramped up the pressure on institutions that have, at best, turned a blind eye to sexual harassment,” says Patel. “It’s been encouraging to see so many women around the world supporting each other, amplifying each others’ voices, and acknowledging how traumatic speaking about sexual harassment and abuse can be.”

A tipping point

So what’s next for feminism? Patel believes #MeToo has created a tipping point. “We’ve got to use this moment to make it clear that we should never tolerate abuse or harassment,” she says, “and we must counter sexist attitudes by placing a higher value on emotional intelligence and empathy in the way we educate and go about our daily lives.”

“I think where we go next is de-centring the linear narrative of feminism,” says Olufemi. “Younger people’s feminism should not only be about identity, but how identity is linked to oppressive structures. Feminism is about more than just the self; feminism includes fighting against austerity, racist policing, borders, prisons and other issues. Learning from the work of older feminists is important, to enable you to think about what works and what hasn’t.” Younis agrees. “More accessible feminism is awesome – that’s what gal-dem is doing,” she says. “Feminism needs to be something everyone can feel involved in, particularly those who have always been told certain spaces aren’t meant for them. As a magazine written by women and nonbinary people of colour we’re providing a platform for those traditionally excluded from these spaces to flourish.”

However, visibility is not an answer in and of itself, and many young feminists believe the real battles are still to come. Patel cites Brexit as “one of the biggest challenges to the rights of women in the UK”. “So much of our equality law is written into EU legislation,” she points out. “Some of the rights we now take for granted could be affected, including rights for pregnant women at work, part-time workers (42 per cent of women work part-time) and women fleeing violence. It’s something we all must campaign to defend.”

Patel also sees global challenges ahead, from the Trump presidency and from the rise of far right groups seeking to restrict women’s reproductive rights and “actively propagate misogynistic attitudes”. “There’s never been a more important time to protest, petition and use your voice to show solidarity with women experiencing violence or oppression,” she says.

“The moment we stop fighting for our rights is the moment we leave them vulnerable to being eroded or taken away altogether.”

A short history of feminism

Historian Dr Lucy Delap says the waves metaphor often used to describe the rise and fall in the popularity of feminism over the years is problematic for many feminist historians because it is impossible to date the periods precisely.

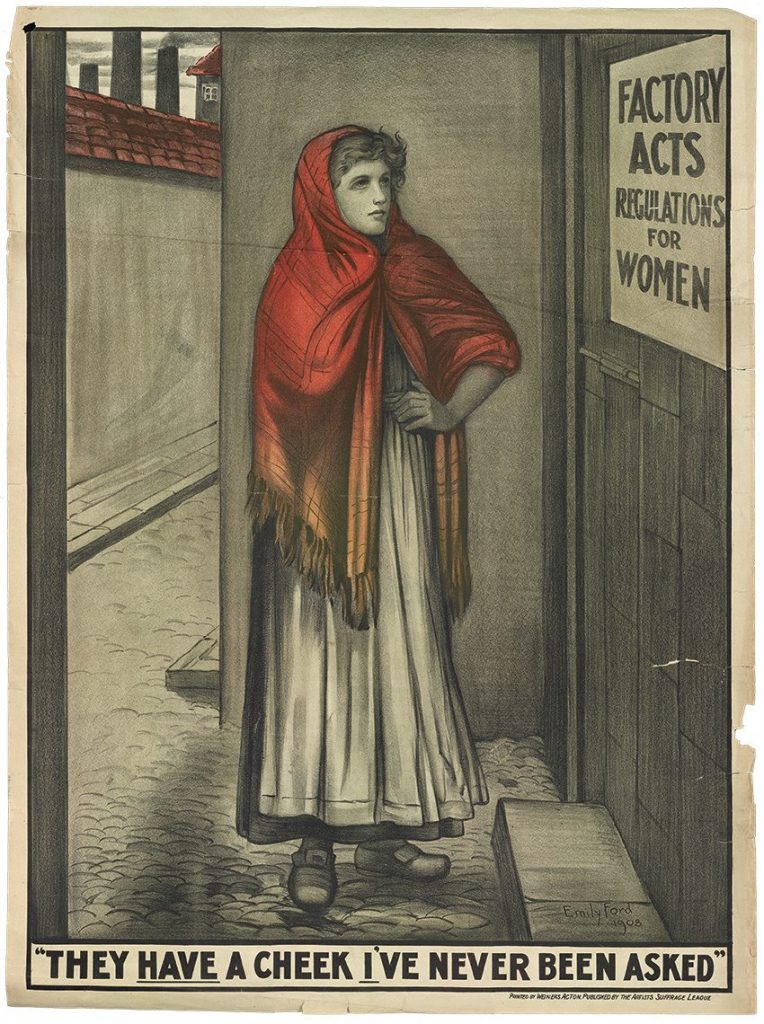

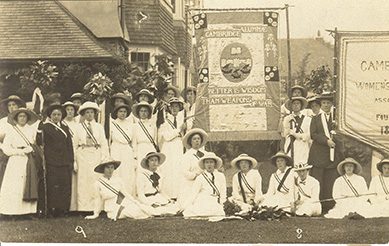

The first wave, she says, is usually agreed to start around the 1860s, when suffragism “became a live issue”, and ends “roughly around the time when some major countries enfranchise women. Women were saying, ‘We want to have equal rights, we want the right to attend university and become a doctor or a barrister – and we want the vote’.” Discussions around patriarchy, men’s sexual objectification of women and sexual harassment in the workplace were also significant.

“It’s about getting back to more material demands for better pay for women, for an end to sexual harassment”

Dr Lucy Delap

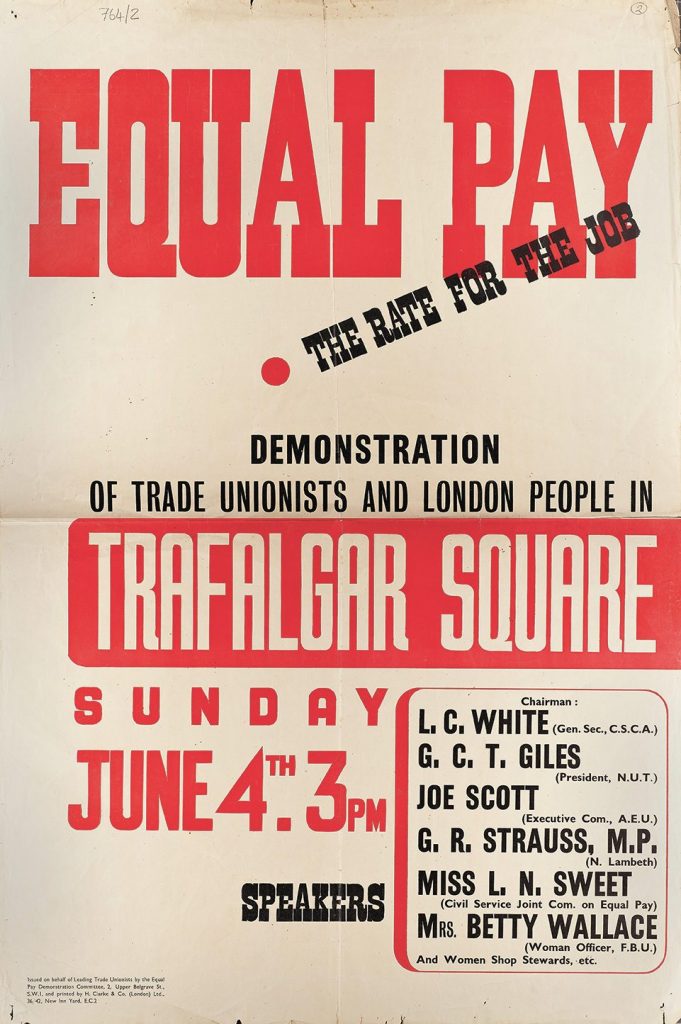

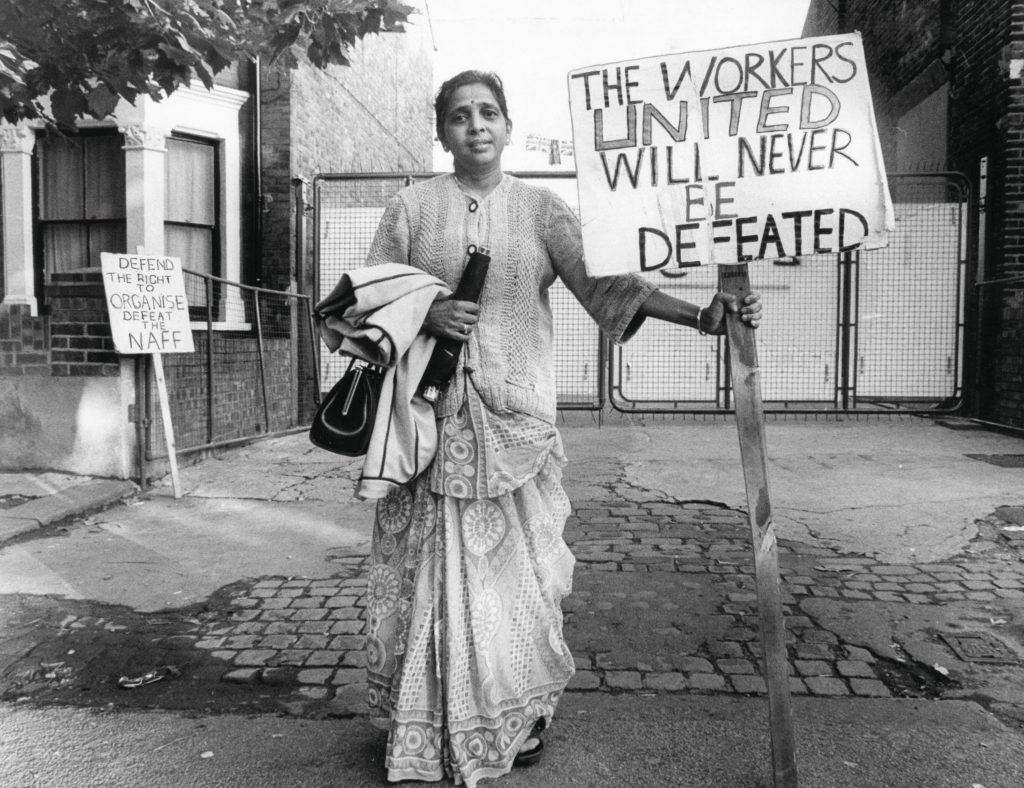

The second wave in the UK, known as the women’s liberation period, is considered to have begun around 1970. The issues that concerned this generation of feminists, Delap says, included sexual objectification, and workplace and gender pay gap issues including representation of women in leadership roles. But the lack of a distinct ending is where the wave metaphor comes unstuck. Many people believe this happens at the end of the 1970s, but Delap points out a “proliferation” of feminism in the 1980s, including the founding of many feminist bookshops and the launch of many women’s studies courses.

The third wave is generally defined as attempting to move towards a more intersectionalist feminism, recognising difference, yet remaining inclusive. “The third wave is seen to be all about young women who are sexy and wear high heels and lipstick, and are still feminists,” she says. “Girl power, riot grrrl, all that stuff, but with a decidedly vague beginning and end point.”

And, in Delap’s view, the fourth wave is still defining its parameters. “Some people would say it’s about media-savvy social-media feminism, about moving away from the culturalist feminism of the 90s – which was to do with the recognition of identities and analysis of language and imagery – to get back to more material demands for better pay for women, for an end to sexual harassment,” she says.

“Something exciting is definitely happening – I notice it among my students. But no-one seems to know what the waves are about. Let’s just call ourselves feminists and be done with it.”