A Jane Austen Guide to the 21st Century

In 2019, Austen’s writing is even more popular than in 1819. And she has far more to say about our digital lives than you might imagine.

What could Jane Austen possibly have to say to the average inhabitant of the 21st century? If you’ve ever taken a selfie, worried about financial insecurity, consulted Dr Google, pondered whether capitalism is really good for you, or spent more of your day than seems sensible following the activities of your friends and relations on social media, then perhaps she has a great deal to say. Indeed, Austen’s later works – Emma, Persuasion and Sanditon – turn on her examination of the moral and social problems of consumerism and the cult of self, issues that continue to preoccupy us today.

Austen’s final – and famously unfinished – novel, Sanditon, is set in a speculative coastal resort, founded on the 18th-century fashion for the seaside, and particularly sea-bathing. From mid-century on, claims for the sea and salt water had accelerated: sea-bathing was supposedly efficacious for “Indigestion, Gout, Fever, Jaundice, Dropsy, Haemorrhages, Violent Evacuations, or any other disorder”, while “inspiring”, or breathing sea air, recovered health more than breathing anywhere inland.

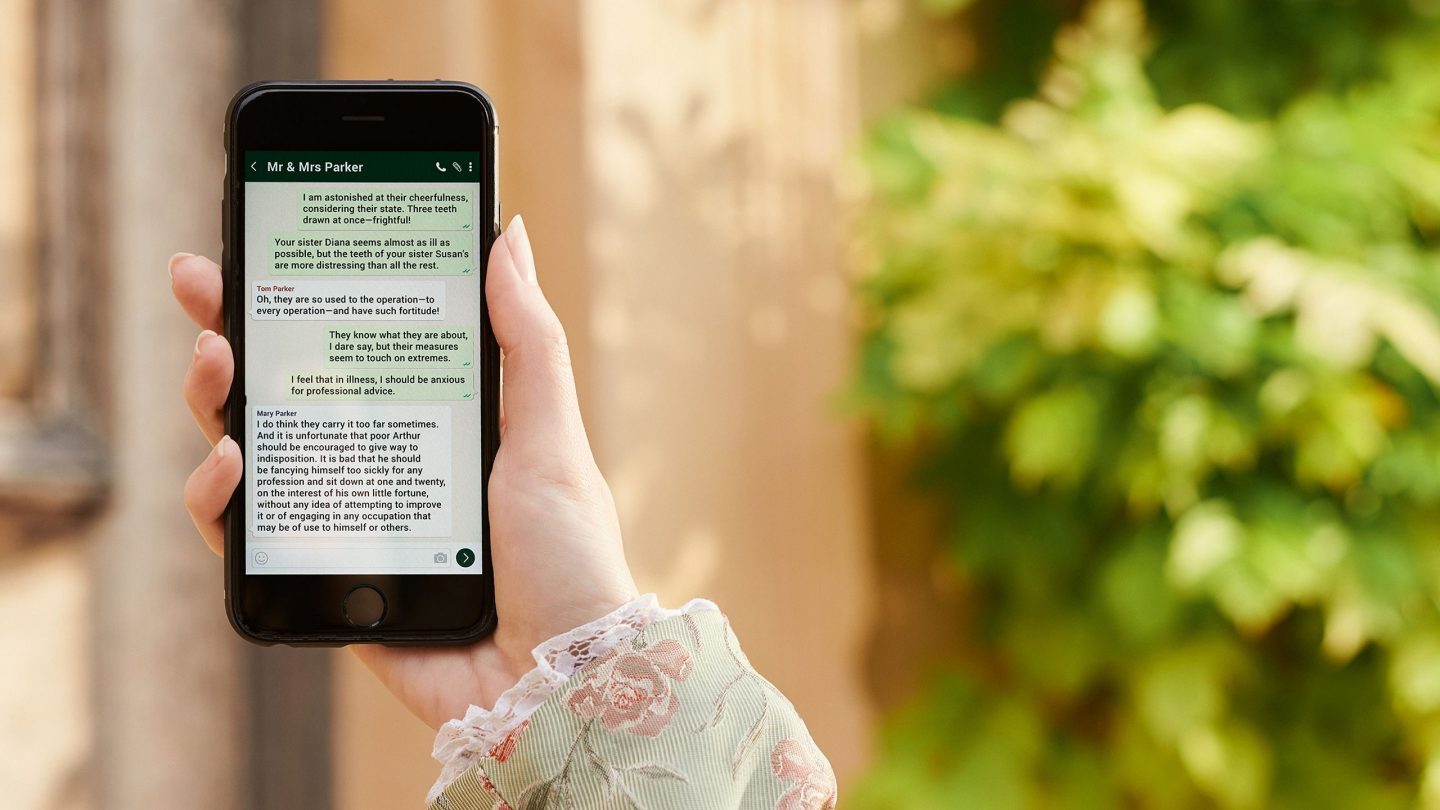

So, despite loving the seaside herself, Austen can’t help but poke fun at such credulity. Sanditon’s Tom Parker holds that “the sea air and sea bathing together were nearly infallible, one or the other of them being a match for every disorder, of the stomach, the lungs, or the blood; they were anti-spasmodic, anti-pulmonary, anti-septic, anti-bilious and anti-rheumatic”. Indeed, literature’s most famous possessor of nerves, Mrs Bennet of Pride and Prejudice, believes she’d be “set up with a little sea bathing” in Brighton.

Austen gives us a picture of health tourism, fads and bodily obsessions that speaks to our proliferating allergies and ailments and propensity to Google untried treatments

Austen gives us a picture of health tourism, fads and bodily obsessions that speaks as much to 2019 as it did to her own time: to our proliferating allergies and ailments, our propensity to Google untried treatments and to believe self-serving salesmen who exploit our bodily self-obsessions. Austen is unsparing in her portrayal of characters as diligent faddists and self-medicators. Diana Parker (Sanditon) declares that the cure for a sprained ankle is to rub it for six hours (provided the friction can be “applied instantly”), and her sister Susan decides that the answer to a headache is to have three teeth extracted (leeches having already been tried and failed). The youngest sibling, Arthur, just 21, declares that his whole right side was paralysed by a cup of green tea – while his sisters believe you should fast for a week after any journey.

Poignantly, the writing of this book was interrupted by Austen’s own ill-health. She would die, aged just 41, a few months later. She perhaps wanted her readers to remember that an obsession with health and self can never change the underlying reality of ordinary sickness and mortality. Which is certainly something to bear in mind next time Dr Google tells you your symptoms equate to a rare, but fatal, illness.

Defined by money

During the depressed years following Waterloo, the national economy was a topic of discussion throughout England. Debate raged in pamphlets and books, in taverns and private homes – and in Austen’s last novel. As today, some argued that the pursuit of self-interest could benefit society generally. Others doubted that the greed and extravagance of the rich would benefit those below them, that wealth inevitably trickles down. Satires noted that the lavish and dissolute lifestyle of the Prince Regent in his elaborate pavilion in Brighton failed to improve the lot of the town’s deprived inhabitants.

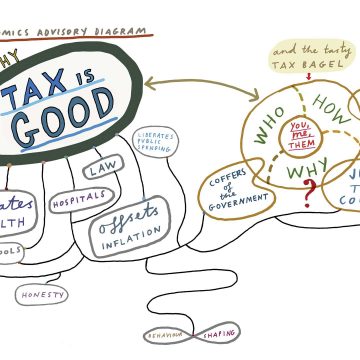

Austen wants to know whether neoliberalism works for everyone in society,

or will it benefit only the few? Is speculation always precarious? Is profit alone a worthy motive? Will the country prosper most under a laissez-faire system or should there always be welfare and paternalistic controls, so that development does not despoil an organic community? The characters in Sanditon debate these questions from differing (well-to-do) social positions.

The traditional, stay-at-home landowner Mr Heywood expresses the reactionary view that society is best when all know their place. Change erodes class divisions, he believes, and disturbs the tested ways of the past. The new resorts are bad because they cause inflation: they raise prices and “make the poor good for nothing”. Mr Parker, traveller and projector, disagrees. He accepts the working of the marketplace: it may disturb the old order, turning traditional fishermen and farmers into commercial sellers, but the new capitalist economy will benefit all in the long run. When the rich spend, they “excite the industry of the poor and diffuse comfort and improvement among them”. Rich and poor are symbiotic: butchers, bakers and traders cannot prosper without “bringing prosperity to us”.

We don’t know where Austen herself stood in the debate – the answer would depend on what fate she was proposing for Sanditon. But in playing out these questions in the private lives of her characters, Austen reminds us that economics is not just a matter for opinion and discussion, but of real life.

Austen’s characters are all, in various ways, defined by money. We know who is landed and who funded; whose fortune derives from trade or an ancestor’s clever speculation. In short, we know what most characters are worth. We also know what they spend money on. Regency England was increasingly awash with consumer goods: indeed, in seaside Sanditon, even foodstuff is imported or bought. And, like the real seaside resorts of the late-18th and early-19th centuries, its shops sell all manner of expensive things that mark status and answer whim: fashionable frocks, lace, straw hats, blue shoes, nankin boots, gloves, books, camp stools and harps. Carriages are the consumer items that best convey status: Sir Edward’s sister – genteel but not monied – is “gnawed by the want of a handsomer equipage than the simple gig in which they travelled, and which their groom was leading about still in her sight”.

If Jane Austen were on Instagram she’d have more followers than Kim Kardashian

Houses, too, declare rank, but, while all Austen’s novels are obsessed with living spaces, none mentions so many kinds as Sanditon, a veritable estate agency of a book, with its terraces, tourist cottages, hotels, and “puffed” (marketed) lodging houses. The whole town is for sale and to let; a sort of seaside theme park. Like the fake palm-leaf huts built to attract modern tourists to the tropics, the resort’s exploiters construct picturesque “rural” cottages. Visitors are consumers who must buy from local shops “all the useless things in the world that could not be done without”. Like celebrities and Instagram influencers now, people themselves become saleable items: Sidney, Mr Parker’s dashing younger brother, is a useful attraction for showy, nubile girls and their scheming mothers. The rich” half mulatto” Miss Lambe is desirable as a paying visitor and as prey for a needy bachelor.

The cult of self

Beneath the activity lurk serious questions. How does consumption affect morality? How does the constant need to buy new things, to enjoy purchasing then throwing away, impact on society and its traditional crafts? Under the urge to buy and sell, will the country dwindle into tourist haunts and shopping malls? Austen asks us to examine our own consumerism as we judge that of her characters. Something to bear in mind, next time you declare yourself immune to online advertising.

If Jane Austen were alive and on Instagram she’d have more followers and friends than Kim Kardashian. She is a global brand: quotations from Pride and Prejudice and a prettified image of its author are instantly recognisable. Yet, beyond a sketch by her sister, which delivers a sardonic, slightly contemptuous image, there is no authenticated portrait of her.

However, as a writer Austen clearly understood the power of images. In Emma, the heroine tries to make her protege attract a suitor by painting her as more impressive than she is. Sanditon’s Lady Denham, twice widowed, lives in the big house of the first husband, while enjoying the title of the second. This classier second holds pride of place on the mantelpiece while the original owner languishes elsewhere in miniature.

The cast of Sanditon are avid promoters of themselves and their hobby horses. The husband-hunting Miss Beauforts arrange their bodies in attractive tableaux at their window – surely the equivalent of generating Instagram “likes” – while Sir Edward intends to make himself irresistible to every pretty girl he meets. The characters’ egoism often prevents success. As in Emma, they rattle on, self-exposing and uninterrupted, allowing Austen to brilliantly mock the cult of self, self-promotion and self-obsession.

“Vanity working on a weak head, produces every sort of mischief,” she wrote in Emma. The hypochondriacal Miss Parkers in Sanditon have an “unfortunate turn for quack medicine” and a “love of the wonderful”. Austen sums them up in words that fit many of the characters in the novel – and many in the 21st century: “There was vanity in all they did, as well as in all they endured.”

Jane Austen’s Sanditon, edited and with an introduction by Janet Todd, is published by Fentum Press. Professor Todd is an Honorary Fellow of Lucy Cavendish.