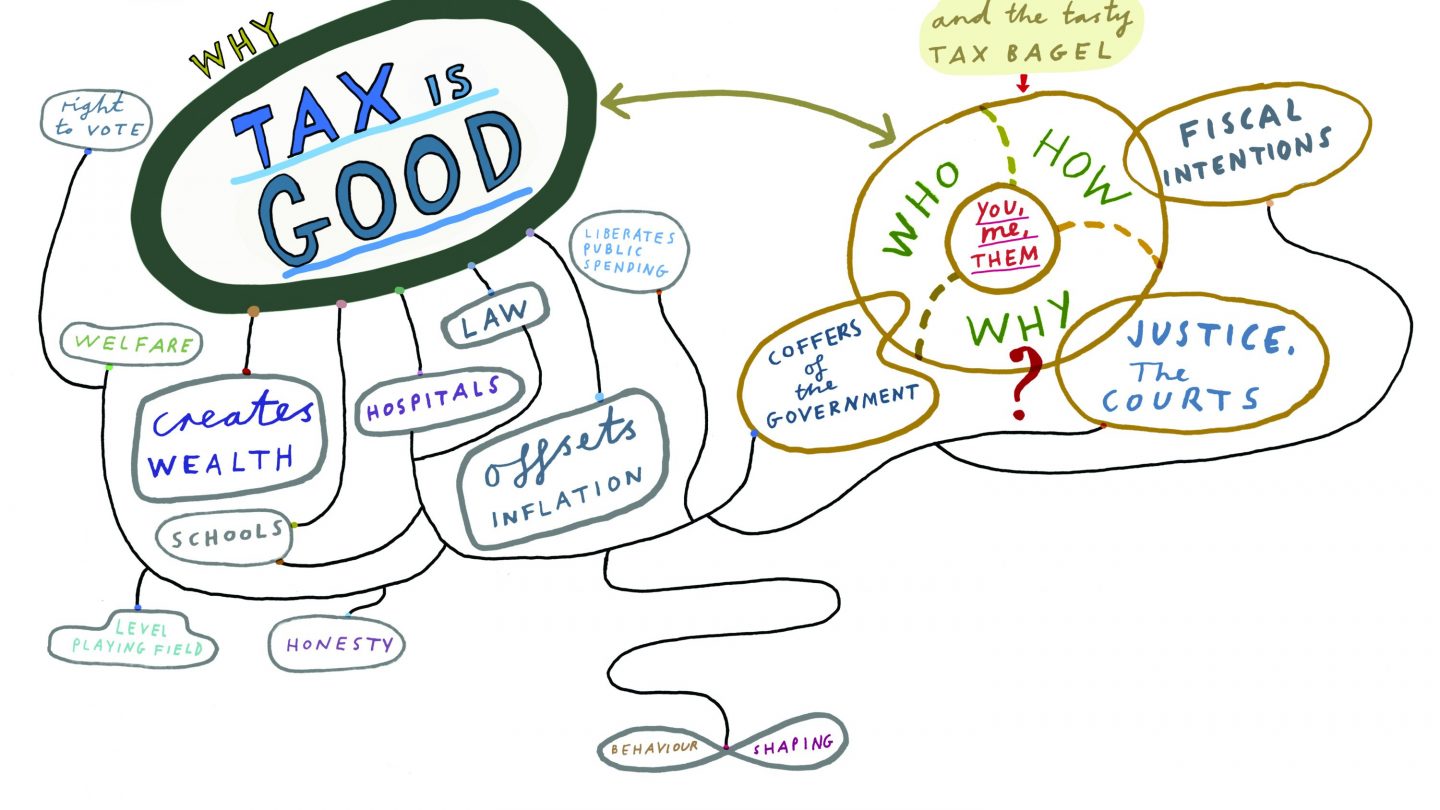

Why Tax Is Good

Tax. It might not seem sexy, but tax policy – who, when and why the state taxes – is at the heart of determining the character of a society. CAM delves into the history and the politics of taxation

The year is 2012. Chancellor George Osborne is confronting a political storm. Business leaders are described as ‘livid’. Jobs are at risk. Headlines are lurid. Faced with such strength of public feeling, Osborne is forced to backtrack. His incendiary proposal? Charging VAT on freshly baked takeaway food – or, as it becomes known, the ‘pasty tax’.

Let’s be honest: the subject of tax only tends to interest people when they think they are paying too much of it – whether on their income or on their hot, baked goods – or if other people aren’t paying enough. But we should pay more attention. Because how we tax, who we tax and why we tax determines what kind of society we become, giving financial expression to our cultural values and priorities. Far from being dry and dusty, taxation is a topic that could not be more political.

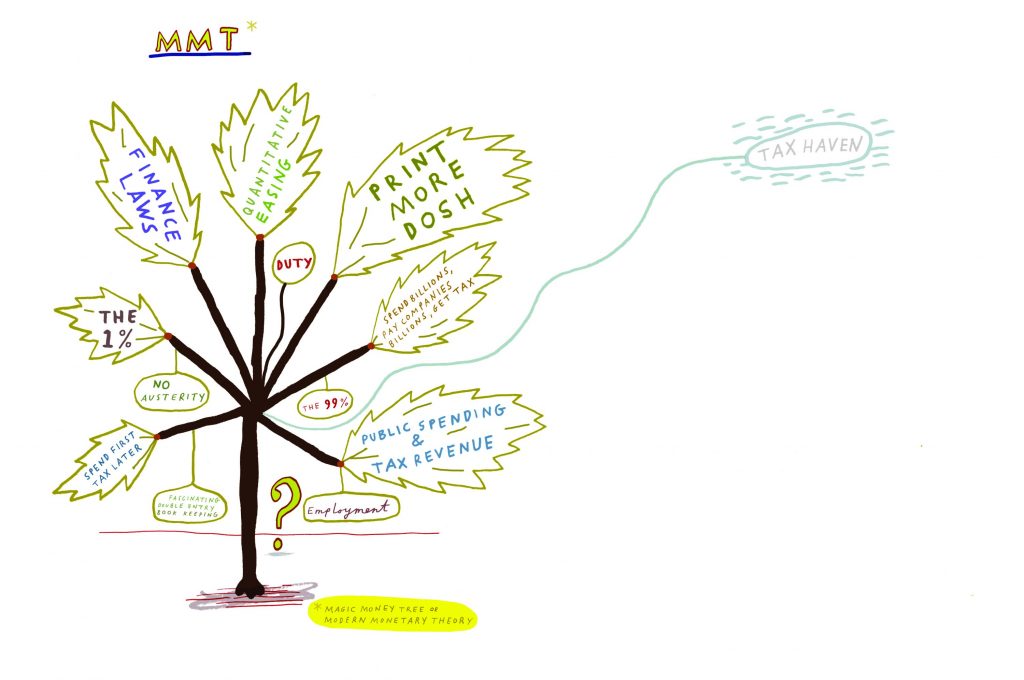

Indeed, for Martin Daunton, Emeritus Professor of Economic History, taxation goes to the heart of fundamental questions. “Fairness, for example. The definition of equality. The difference between passive wealth, such as inherited wealth, and active wealth,” he says. Daunton cites the huge differences between countries such as Sweden (where high taxation sits alongside a well-funded state) and the zero income tax regimes of many of the Gulf states, where petrol is subsidised and the rallying cry of ‘no taxation without representation’ would appear to be inverted (free from the need to tax their populace, rulers are free from the need to give them representation too). Daunton points out that these issues are now also international: national revenues are threatened by tax havens and the ability of large companies to book profits in low-tax regimes.

Tax is political even when it doesn’t feel political

In fact, tax is political even when it doesn’t feel political. “The pasty tax is a classic example,” says Dr Dominic de Cogan, Lecturer in Tax Law. The economic thinking behind it made sense: if you reduce the number of exemptions to the ordinary application of VAT, you get a tax that, from a technical point of view, works better. It causes fewer economic distortions and raises more money with less damage to the economy. But because the pasty tax was frameable as an attack on the working class, it was easy to bring down. That’s why some of us working in tax feel that it can’t easily be divorced from political considerations. If anything, it is primarily politics. Economists and lawyers can advise. But ultimately, parliament makes the decisions.”

Those decisions can start, win and lose wars. The English Civil War was fought, in part, over the question of whether the Crown had the right to raise tax revenues on its own authority, or whether it needed parliament’s authority. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 marked the beginning of annual parliaments, which allowed negotiation over what was taxed and by how much. “The result was an effective tax state in Britain,” says Daunton. “And that means that although France had a lower tax rate than Britain, they had more tax revolts because their taxes didn’t have the legitimacy of parliament. “The consequences of this cannot be overstated. British governments were able to use tax revenue to borrow money, which the French couldn’t. And that meant that they could defeat the French and fund the beginnings of the British empire.”

For an extreme example of how the decision to tax – or not – can shape an entire society, look to the Cayman Islands. In the 1960s, British Caribbean crown dependencies were asked if they wanted to become independent of the Crown. Three chose to stay: the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. “So the UK said: fine, but we want you to develop your own economies,” says May Hen-Smith (Jesus, PhD), a specialist in economic sociology, who is currently working on a 10-year longitudinal study of women in the offshore financial industry. “The Cayman Islands was primarily a maritime economy. It’s a land of volcanic rock: there was no plantation economy, like Jamaica. They didn’t have tax, because they never really needed it.”

The then government brought in laws to encourage the banking industry, and the offshore financial industry was born. Today, the Cayman Islands is the fifth-largest financial centre in the world. It has no corporation tax and no income tax, although as Hen-Smith points out, there are still some taxes such as a 20 per cent stamp duty on imports: expect to pay around £7 on a cauliflower from Miami.

You’re made immediately aware of your status as a ‘non-belonger’ in the immigration line – the ‘belongers’ line is exclusively for British Virgin Islanders.

“We think of tax havens as bad,” she says. “But if you’re in the Cayman Islands and you’re asking the indigenous population, they’ll tell you that their peers in the surrounding Caribbean islands consider them an economic success story. “For a small island with no economy, no arable land, no infrastructure, to become this powerful nation is huge. “There are always going to be tensions between expatriates and locals, but islanders know that this is a very precious part of their economy. So they cooperate, in order to maintain their global competitiveness.” And tax havens, she points out, are under increasing pressure to compete: a relatively new phenomenon has seen onshore jurisdictions borrow or copy offshore products and services to bring business their way.

Levies and the invisible Amazons

On other islands, the finance laws have worked in different ways. The culture of the Cayman Islands, says Hen-Smith, has always been open to outsiders and visitors. On the British Virgin Islands, however, there’s a stronger tradition of islander and outsider identity, and the island’s offshore legal apparatus is one way in which that islander identity is expressed. “So much so, that there is now a legal term in their statutes: belongers,” Hen-Smith says. “You’re made immediately aware of your status as a ‘non-belonger’ in the immigration line – the ‘belongers’ line is exclusively for British Virgin Islanders.”

The questions and complexities that surround the effect tax has on societies are not likely to go away soon. One of the biggest Brexit questions, de Cogan points out, is around how customs will work at the Irish border. “At the moment, we don’t have border posts where customs duties are assessed and where product safety is checked before goods travel from one side of the border to the other. And now these levies, which most of us have ignored since the 1970s, are suddenly an issue again.”

Governments are failing to tax companies such as Amazon and Google as much as they might like, in part because they are not physically located anywhere

Indeed, any discussion of identity and nationhood must almost always – in the end – result in a conversation about taxation. Take Scottish and Welsh devolution, for example. “The Scottish parliament is trying to get more control over revenues and also tax rules, says de Cogan. “I see that in the light of capacity building: if Scottish institutions have autonomous control over revenue streams, then they can become more distinctive. “What’s particularly interesting is that some of the practices in Scotland have been picked up by Wales in terms of devolved best practice.”

The obvious one is income tax, over which Scotland has had rate-varying powers since the 1998 Scotland Act – but which it hasn’t used much. “Recently, however, it has decided it does want to diverge and have a different income tax structure,” de Cogan says. “Once Wales and Scotland start coordinating, then they start to build up this common idea of what it means to be a devolved nation, what kind of powers they want and how they finance that. And that starts to build a very different idea of what the United Kingdom is.”

Alongside grappling with the implications of tax regimes defined by geography, governments must also grapple with companies that defy geography altogether. “Governments are failing to tax companies such as Amazon and Google as much as they might like, in part because they are not physically located anywhere,” says Hen-Smith. “And from an offshore perspective, that prompts questions like: what would an offshore tax regime that only existed digitally look like? “How is the Cayman Islands going to compete with a domicile that has no physicality? “The absence of taxation really scares everyone. And places that tax authorities can’t touch scare them even more. “But I think we need to get past the old idea of what a tax haven is and start thinking of them as places where really interesting things are developing from a socio-economic and socio-legal perspective.” However, while tax might drive history, it also has an immediate, everyday impact on every one of us. Critical tax theory is an area of study that focuses on how the tax system impacts on women, LGBTQ+ people, ethnic minorities, immigrants and other marginalised communities. “There is compelling evidence, particularly in the States, but to some extent in the UK as well, that tax rules can affect the experience of women in society,” says de Cogan.

Imagine, for example, a decision to tax a high-earning couple as a unit, rather than as individuals. If one partner is a full-time parent, returning to work would subject their income to a very high tax rate – making it – financially – extremely unattractive to re-enter the workforce. “It may not affect that many people, but it’s symbolic,” says de Cogan. “It says: this is how we view you and this is how we value your work and this is how we are going to treat you. This is probably the most cited example of this kind of under-the-surface discrimination. “To make things more difficult, it isn’t about somebody sitting in a chair on high, deciding to discriminate. It’s a logical decision that has to be made and there are arguments both ways, but it creates difficulties, whatever you choose. And it shapes how you want your society to be.”