Philanthropy Matters

The campaign for the University and Colleges has passed the £1bn mark. So why does philanthropy matter to Cambridge?

What does the Cambridge Professor of Innovation carry in his pocket? It sounds like a question worthy of an admissions interview. And if it were, it’s unlikely that even the most lateral-thinking of candidates would guess what Professor Tim Minshall keeps with him as a reminder of his mission: a small thermostatic switch, exactly like the one found in almost every electric kettle.

It’s a nod to the philanthropist who donated £2.5m to fund Professor Minshall’s chair. Dr John C Taylor is one of Britain’s most successful and prolific inventors, with more than 400 patents. He made his name by creating the small bimetallic thermostat that ensures electric kettles switch off when the water reaches boiling point – though he’s arguably best known to Cambridge students as the creator of the Chronophage clock that gobbles up time outside Corpus Christi.

Professor Minshall, who took up his post in September 2017, says: “When anyone asks me what innovation is about, we can talk about Tesla and Uber and machine-learning and going to the moon. But I can say ‘It’s also this’ and produce this device. It shows that innovation means spotting an opportunity, understanding what technology could be used to address it, developing the solution that uses the minimum necessary resources, and getting it to market where it can improve people’s lives.”

The creation of the Dr John C Taylor Professorship of Innovation is a clear example of why philanthropy is of such crucial importance to Cambridge, and to every modern university. Without the donation, it simply wouldn’t have happened. The story is repeated throughout the University’s Schools, Faculties, Departments and Colleges.

Battling on all fronts

Philanthropy has enabled Cambridge to address the most critical issues of our time. It has supported ground-breaking research into treating Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, addressing global biodiversity loss and gaining a deeper understanding of the economic challenges of African nations. Without it, new centres such as the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute and the Centre of Governance and Human Rights would not have been founded.

Benefactors have funded academic posts to attract the brightest minds to Cambridge, and countless scholarships and bursaries to help the most financially disadvantaged undergraduates meet the cost of their studies. Above all, philanthropy acts as a guarantor of independence and intellectual freedom. It makes academics less vulnerable to reversals in government policy or changing trends in research-council funding, allowing them to concentrate on ambitious long-term goals.

“It’s not just about the income. It’s knowing that there are people who believe in you enough to support your journey through higher education.”

Mollie Georgiou (Queens’ 2016)

It’s certainly not all about seven-figure bequests from individuals or charitable foundations; small, monthly direct debits from alumni add up to a vital enabling force. “We very strongly believe that any gift, however small, is extremely important and each one is received with huge gratitude,” says Professor Chris Dobson, Professor of Chemical and Structural Biology and Master of St John’s.

“Long-term philanthropic success for an institution such as Cambridge involves a large proportion of our alumni being aware of our needs and enthusiastic to support us in achieving our ambitions.”

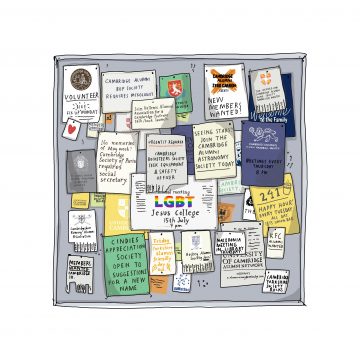

Cambridge is driving this success with a major campaign. Launched in 2015, the Dear World… Yours, Cambridge campaign aims to raise £2bn for the University and Colleges from alumni, friends and supporters. To date, more than 47,000 donors have responded to the call. The campaign’s co-chair, Sir Harvey McGrath (St Catharine’s 1971), is clear about the impact this is already having. He says: “As a result of this support, we are able to attract, inspire and support the brightest in the world, irrespective of their background or financial capacity. We must continue to do so, to ensure that students who would not otherwise be able to come to Cambridge have the financial support they need, now and in years to come.”

In December 2017, the tally was propelled through the £1bn mark by an £85m donation to the Cavendish Laboratory from the estate of Ray Dolby – the pioneer of acoustic technology.

“Reaching £1bn is an outstanding achievement,” says Vice-Chancellor Professor Stephen Toope. “It reflects the extraordinary commitment of so many alumni and donors to the Collegiate University. Cambridge has had a huge impact on the world for more than 800 years, and our role in society at a time of increasing global complexity and anxiety is more important than ever.”

Clinical research

Stem-cell research and immunotherapeutics are two areas to have benefited greatly from philanthropy. On its completion later in 2018, the new Capella Building will bring scientists together in a purpose-built lab on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus. Patrick Maxwell, Regius Professor of Physic and Head of School of Clinical Medicine, says: “Historically, we have been brilliant at getting money to fund the actual expense of doing the experiments. But there is very limited government funding for anything like new buildings or key long-term posts.

There is a strong consensus in Cambridge that philanthropy is no longer an optional extra

“In this instance, people working on stem-cell research, regenerative medicine and immunotherapy have been scattered around the University, because they have roots in lots of academic disciplines that were organised that way 20 to 30 years ago. The new building will bring people together from different departments in a facility with state-of-the-art equipment.

“It’s one of the drivers for our brilliant biologists that they want to see their discoveries taken through to patients, and to make that happen they needed to be up here on the hospital site, integrated with clinical scientists. Without the new building, there was no space for them to do that. And we couldn’t have done it without philanthropy.”

Professor Dobson has been deeply involved with fundraising at both University and College level. A notable success on the research side has been the financing of the Centre for Misfolding Diseases – a specialist unit within the Department of Chemistry pursuing research into disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. The Centre will be based in a new Chemistry of Health building that has been made possible through support from donors, including £20m from the Elan Corporation and £5m from Emmanuel alumnus R Derek Finlay, after whose wife, Una, the Centre’s new laboratories will be named.

College campaigns have been equally successful. “Our current campaign at St John’s aims to raise £100m, and we’re now about halfway towards that target,” says Professor Dobson. “What’s particularly exciting is that this campaign is strongly focused on enhancing support for our academic activities – not least the help we can give to students from low-income backgrounds, for example.”

Recipients of philanthropic support via their College include Hannah Lawson (St John’s 2017), a first-year undergraduate in Human, Social and Political Sciences. She is one of two candidates in her year to receive a Salim and Umeeda Nathoo Bursary, which provides £5,000 a year for the duration of her degree. The bursaries are intended to help outstanding students meet the cost of living and learning in Cambridge.

“I applied for the bursary the summer before I came up to Cambridge and was interviewed by Mr Nathoo along with the Senior Tutor and the Scholarship Administrator at St John’s,” says Lawson. “I worked to earn money for university and had some savings, but the bursary means that my time in Cambridge can now be devoted to studying and pursuing work experience.”

University-wide schemes are equally significant in helping all undergraduates make the most of a Cambridge education. Now in her second year, Mollie Georgiou (Queens’ 2016) was awarded a Reuben Scholarship when she was accepted to read Psychological and Behavioural Sciences. The scheme, founded by brothers David and Simon Reuben, provides bursaries for talented students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

She says: “I was the first person from my school to go to Oxford or Cambridge, but I didn’t know about the scholarship before I applied. I receive the money from the scholarship on a termly basis, and it provides reassurance that I can take part in all the things that other students can. I can do my weekly shop and pay for events without worrying about financial pressures. I was also able to buy a laptop, which makes it a lot easier to access the resources I need.

“The networking side of the Reuben Scholarship is important – we help and support each other. When you come to Cambridge from a state school, you don’t necessarily have a ready-made network. We keep in contact via email, and I’ve been invited to the Reubens’ house in London to meet other scholars from Oxford and UCL as well as Cambridge.”

Georgiou strongly believes that scholarships such as hers attract a more diverse set of applicants to Cambridge. “It’s not just about the income,” she says. “It’s knowing that there are people who believe in you enough to support your journey through higher education. They’re also an acknowledgement of the wider issues that can prevent candidates from trying for Cambridge: ‘How could I thrive in an environment like that, when I haven’t had that sort of academic experience before?’ Scholarships encourage academic confidence and help people believe in themselves.” The Vice-Chancellor, Professor Stephen Toope agrees. “Scholarships and bursaries are critical to Cambridge’s ability to attract the very best students regardless of means,” he says. “We need to do much more going forward, and philanthropic support is key to this endeavour.”

Ukranian conflict

Many schemes exist to support researchers at the start of their academic career. The Gates Cambridge Trust, established by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, confers scholarships on “intellectually outstanding postgraduate students with a capacity for leadership and a commitment to improving the lives of others”. They include Ukrainian poet Iryna Shuvalova (St John’s 2016), whose award has allowed her to pursue a PhD in Slavonic Studies. Her work examines the role of poetry in war, and how it has helped people in eastern Ukraine to cope with the trauma caused by the ongoing conflict.

She says: “Cambridge has one of the best Ukrainian Studies programmes in the world, but as I couldn’t self-fund, I had to explore how I would finance my research. The Gates Cambridge Scholarship was the best option for me because I have a daughter: it’s the only one that offers support for dependants.

“In my research, I’m bringing together traditional songs and contemporary oral poetry, looking at how the earlier material becomes re-actualised and reinterpreted in the current conflict. The independence that scholarships provide is immensely valuable, and especially when we tackle sensitive political issues.”

Ultimately, there is a strong consensus in Cambridge that philanthropy is no longer an optional extra, if ever it was: it’s now a vital factor in enabling the University to maintain academic independence and pursue its mission at a time of unprecedented financial pressure. “I’ve been in Cambridge for over 15 years,” says Professor Dobson, “and in that time the attitude to fundraising has changed beyond all recognition. Everyone is convinced that it’s a vital part of our ability to remain a world-leading university.

“Our alumni are tremendously enthusiastic supporters of our objectives, and I believe they feel increasingly strongly connected to the University and its Colleges. In turn, we are keen to encourage them to see for themselves the effects of their donations and to meet the students and academics whose activities they are supporting. In the end, their gifts are the bedrock of our future success as a major centre of teaching and research, and we could not be more appreciative of their generosity and encouragement.”

-

Key facts and figures

- £1.13 billion: amount raised by the University and Colleges since the start of the campaign

- £2 billion: campaign goal

- 47,000: number of contributors to the campaign to date

- 49 per cent: percentage of total raised to date given by alumni

- 267: number of new graduate studentships funded by philanthropy

Learn more about the campaign.