Transcribing history

Living through, and with, a pandemic might be new to the denizens of the 21st century – but for people living in early-modern Japan, it was all too familiar. Now, a new transcription project – and a new generation of students – are bringing these specialist texts to a wider audience.

Hidden deep among a swathe of early-modern Japanese texts, the details of how people dealt with the horror and trauma caused by pandemics in the past could shed light on the way we tackle similar challenges today. Yet these details are so well hidden that only a very few can decipher them.

Written in now-obsolete kuzushiji (a flowing cursive script-style) and using hentaigana letter-forms, the texts are inaccessible to all but a tiny minority outside of Japan. But now, thanks to a special summer school programme that harnesses cutting-edge artificial intelligence, their secrets have been unlocked.

The groundbreaking collaboration saw Dr Laura Moretti, who has run the Summer School in Japanese Early-Modern Palaeography for the past eight years, team up for the first time with Professor Hashimoto Yuta of the National Museum of Japanese History. Their project has produced a newly transcribed archive containing books and ephemera discussing a range of different epidemics (and what to do about them), and a new generation of scholars who have been trained to decode, read and analyse these materials.

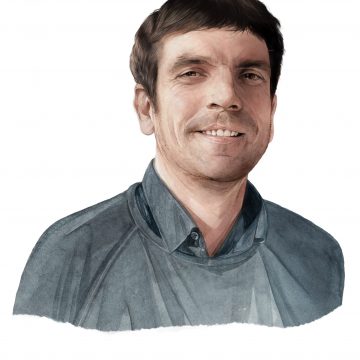

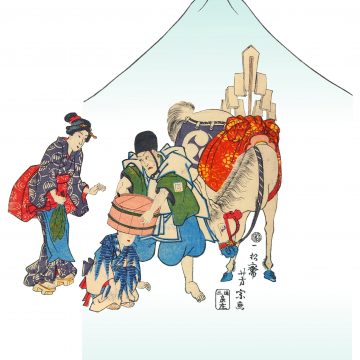

Colour print from woodblocks. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

“Early-modern Japan had a booming commercial publishing industry,” says Moretti, Senior Lecturer in Pre-Modern Japanese Studies at the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies. “But we decided not to work on the abundant medical treatises, which were written in kanbun kundoku” – that is, Chinese script with a Japanese reading. Instead, the focus was on hentaigana and kuzushiji, which even Japanese people can’t read without training.

That makes swathes of historical records inaccessible to all but the most dedicated scholar, be they Japanese or Western. And it’s why, in 2017, Hashimoto developed an AI platform named Minna de Honkoku (Transcription Together) that assists scholars reading Japan’s famously obscure early-modern writing. “Although these programs are relatively simple by the standards of AI technology, they greatly facilitate participants’ reading and writing of kuzushiji,” explains Hashimoto. And when Moretti decided to take her programme online in 2020, Minna de Honkoku seemed the obvious solution.

There’s one heartbreaking description of thousands of bodies thrown into the bay at Shinagawa. I was reading this when news broke of my hometown struggling with so many bodies of Covid victims they had to call in the army. That resonated deeply with me

Moretti’s chosen sources – some already digitised through such institutions as the National Diet Library and the National Institute of Japanese Literature, others newly captured in digital format – were digitised and added to Minna de Honkoku. The 20 or so texts represented a wide range of formats and subjects “to see how popular discourse around diseases was created”, says Moretti, with the common factor that almost none had previously been transcribed. Some of the volumes are informational, “such as popular guides to measles that detail symptoms and how to treat them”. Others are fictional, such as a charming picture-book showing toys rescuing children. “It’s even printed in red, an auspicious colour believed to help defeat smallpox,” she says.

Aside from the primary goals of transcribing hitherto inaccessible texts and advancing the palaeographic and digital skills of a cohort of scholars, the analysis generated insights into its all-too-timely subject matter – how societies respond to pandemics. “These books make us realise the tragedy of these diseases,” says Moretti, citing an account of a cholera pandemic. “There’s one heartbreaking description of thousands of bodies, so many no one knew what to do with them, which were thrown into the bay at Shinagawa. I was reading this when news broke of my hometown, Bergamo, struggling with so many bodies of Covid victims they had to call in the army. That resonated deeply with me.”

Other texts strike a more hopeful note. “Even the one about cholera ends with short stories giving people’s names and explaining how they managed to survive,” says Moretti. “Hope was strongly present.” As, too, was the perhaps more unexpected element of humour, which Hashimoto had encountered in comic responses to earthquakes in his previous work.

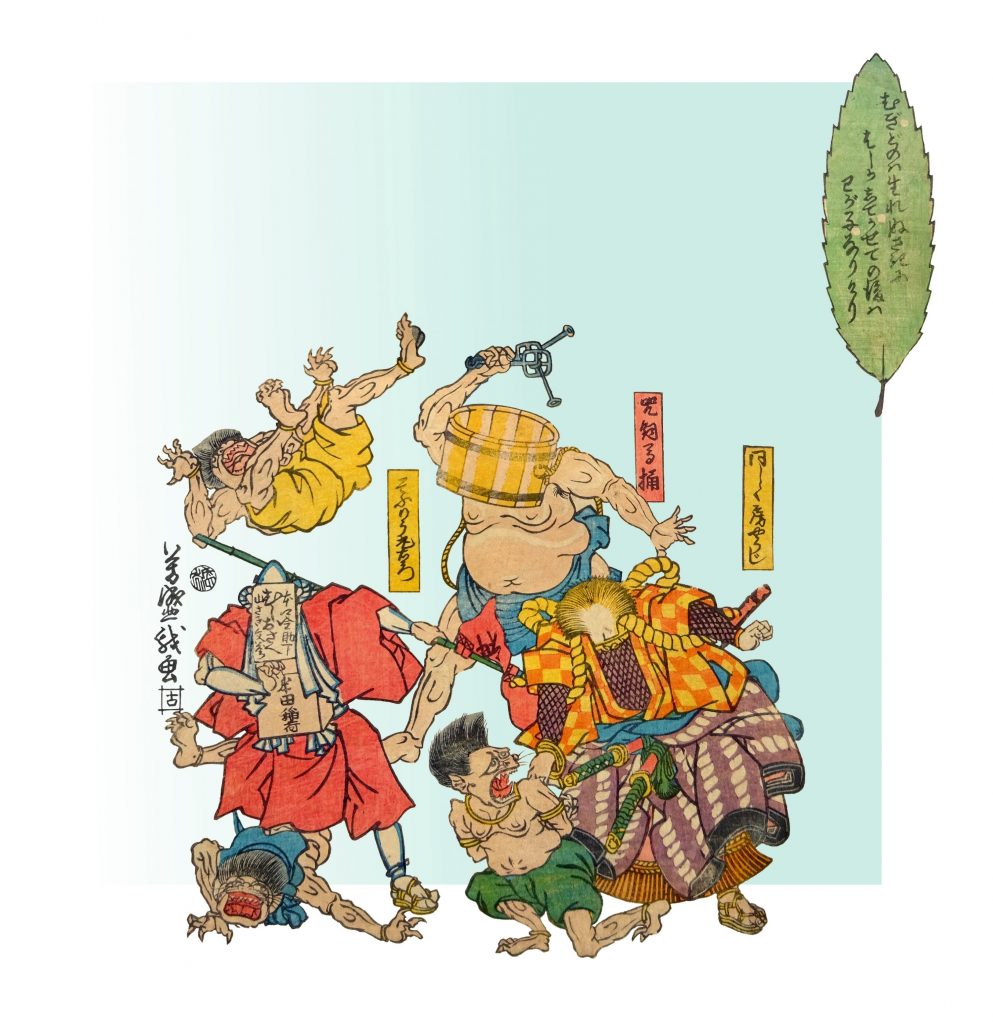

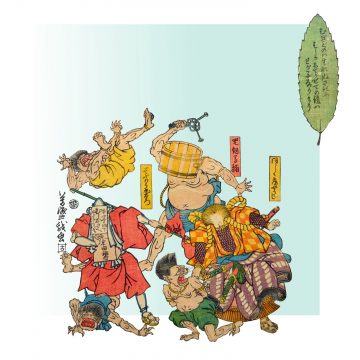

Colour print from woodblocks. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

“Immediately after the Ansei Edo quake, which struck Edo (modern-day Tokyo) in 1855 and took the lives of more than 4,000 people, hundreds of types of prints began to appear. Most of the prints depicted giant catfish, a type of image known as Namazu-e, and were based on the myth that these giant catfish were living under the earth and causing earthquakes.”

Noting that a Dutch anthropologist, Cornelis Ouwehand, has suggested that one function of Namazu-e was to enrich the lives of the people affected by the disaster by providing them with ridiculous vulgar jokes and laughter, Hashimoto speculates that “perhaps the Japanese of the early-modern period were similarly trying to alleviate the intense stress and trauma brought about by plague, through humour and laughter”.

Another strand was the role of faith in supernatural forces. This especially piqued the interest of Anna Dulina, participating from Kyoto University where she is a PhD student studying medieval religions in Japan, who was intrigued “to compare religious thought of the medieval and early-modern period in the context of pandemics. For example, I was surprised to learn that people were permitted to freely collect stones from a shrine’s grounds to use as amulets to protect children from smallpox, even though the sale of amulets was a way for shrines and temples to raise money.” Dulina believes the newly transcribed works will prove valuable “in various research fields, such as culture, literature, religion, history and art”.

Above all, what shone through for Moretti was the way the texts “make us grasp that what we have experienced now with Covid is not as unprecedented as the media keeps saying. Human beings have lived through pandemics many times across history. These people went through exactly what we are going through now – and survived.”

It is a message that is perhaps underscored by the mutually supportive and collaborative nature of the online school itself, with scholars participating across every timezone, from the west coast of America to Japan. James Morris, an Assistant Professor at Japan’s University of Tsukuba, was one of the scholars using artificial intelligence as an integral part of a transcription project for the first time.

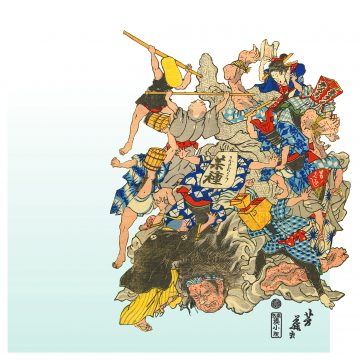

Colour print from woodblocks. Private collection Suzuran bunko (Cambridge).

“The user draws a box round a specific character with their mouse,” he explains, “and is presented with a number of suggestions as to what the character might be. The user can then confirm the correct one, potentially with the use of other tools, or with knowledge from the context of the passage. Minna de Honkoku requires human judgment on its suggestions.” The experience, he says, is “a wonderful lesson and model for those involved in the digital humanities – digital tools are not made to replace humans, but to aid us. The project was a fantastic example of how human and machine can work together.”

The range of formats provided variety not only in subject matter, but also in the all-important paleography. “It was very beneficial working with such a wide range of texts in various styles,” says participant Freddie Feilden, a first-year PhD student at Trinity College. “This meant familiarising myself with many different types of handwriting, which is an essential part of early-modern Japanese palaeography.”

In its reinvention and continuation, the 2020 project became a mirror of the time and the texts it has unlocked – a place of resilience, adaptation and mutual support. “It kept us together and connected despite each of us at various points going through lockdown in their own country,” recalls Moretti. “It really was a saving grace in a difficult time.”

-

Hashika (measles)

At the end of the Edo period, measles outbreaks typically occurred once every 20 to 30 years, usually coming into Japan from elsewhere. The disease would race through the population with a very high infection rate among those born since the previous outbreak. The onset of measles was rapid, widespread and affected both children and young adults.

-

Hashika-e (measles pictures)

Hashika-e were part of a general phenomenon during the 19th century of depicting the abstract causes of calamity and disease in concrete visual form. They feature mixtures of magical and talismanic text and visual symbols – attempts both to explain and to limit the severity of calamity and disease.

-

Defeating the measles demon

This dynamic image captures the moment when the gigantic ‘measles demon’ is being brought down. Defying and defeating the demon are those townspeople whose occupation was most adversely affected by the disease. For example, sexual intercourse was discouraged, and a prostitute possibly employed in the pleasure quarters is joining in, brandishing her wooden pillow (on the upper right).

-

How to fight measles

Food was an important part of the fight against measles. Prints and books in the vernacular on the subject are very keen to list what edibles could help defeating the illness: sweet potato, kelp and Japanese radish, for example. But many things had to be avoided, including spicy and greasy dishes.

-

Hashika (grain husks)

Food was not the only way to fight the disease. Early-modern materials teach us about other practices. For example, placing an empty horse-feeding bucket over the head was thought to be efficacious, because the bucket had once contained grain husks (in Japanese hashika, homonym for measles), but now the hashika is gone. The use of phonetic script for the word hashika would have allowed this play on words.

-

Majinai (magical rites)

Magic, even verbal magic based on play on words, was believed to help fighting measles. Monkey dolls appear in some prints because saru (monkey) is a homonym of the verb saru (to leave). Deities also played an important role. The so-called Lord Wheat is depicted here as a mendicant monk of the Handa Inari Shrine, donned in red, a colour believed to protect from smallpox.

-

Lord Wheat got measles before being born. The pustules are now gone, and healed is my child

Magic was believed to help fighting measles. One of the most famous procedures was to write the afflicted person’s name and age on the back of a tarayō (Ilex) leaf along with the short verse that appears on the leaf in this print. The leaf is then placed in a river or stream to be swept away by the current, hopefully, along with the disease. If you have no Ilex leaf at your disposal, we are advised to cut the paper leaf on the print and use it in place of a real leaf.

Dr Laura Moretti is author of Pleasure in Profit: Popular Prose in Seventeenth-Century Japan. For more on the project, visit wakancambridge.com and cambridge.honkoku.org