Reasons to feel hopeful

Living through dark times can be challenging. It takes resilience, courage and, above all, hope. But what is hope exactly? CAM investigates.

Hope, as Emily Dickinson famously wrote, is the thing with feathers. A thing, perhaps, like the bittern, an elegant, secretive brown heron known mostly for its eerie, booming mating cry, which used to echo across its native wetlands in Suffolk and Lancashire. Over the decades, the seas rose and the edgelands moved ever inland. The wetlands vanished and the bitterns did, too. By 1997, they were almost extinct in the UK: there were just 11 males left.

But now, thanks to the RSPB’s wetlands at Lakenheath Fen (created on the site of former carrot fields in Suffolk), the bitterns are booming again. Eight to 10 breeding males live on just this one site. “It’s like the Field of Dreams,” says Andrew Balmford, Professor of Conservation Science and organiser of the #EarthOptimism summit. “If you build it, they will come.”

There’s a feeling that it’s better to keep your expectations low. But that way of thinking doesn’t make us happy. We’re just neither happy nor sad

If there is hope for the bitterns, then surely there is hope for us. This is not a fashionable point of view. Faced with doomsday headlines about the death of the planet, the rise of demagogues and the horrors of war, hope seems, well, a bit naive. Hope is the Disney princess mouthing platitudes. Hope is the mug festooned with an inspirational self-help slogan about living your best life or following your dreams no matter what.

This kind of hopelessness can be almost superstitious, says Olivia Remes, anxiety and depression specialist and postdoctoral researcher at the Cambridge Institute of Public Health. It is as if hoping for something might somehow prevent that good thing from actually happening in the future. “It’s that feeling that it’s better to keep your expectations low, because we don’t want to wind up disappointed if it doesn’t work out. But that thinking doesn’t make us happy. It keeps us in that low state. We’re neither happy nor sad,” she says. “And wouldn’t you rather have a life with ups and downs, like waves, so that you do actually experience great happiness – rather than just a flat line?”

So we can’t abandon hope: it can change things. Think of a presidential campaign that has harnessed hope, and the viral image of then presidential candidate, Barack Obama, with the single word HOPE underneath may spring to mind. But Obama was by no means the first to harness the power of hope in a political campaign. In 1984, Ronald Reagan’s famous campaign advertisement announced: “It’s morning again in America.” He talked of “a springtime of hope”, recreating far older tropes and ideas of America as the place where huddled masses could be free. It chimed with voters weary of divisions. “In the 1960s and 70s, hope had ceased to be a unifying dream for Americans from all walks of life,” says Gary Gerstle, Paul Mellon Professor of American History. “As Malcolm X famously said: ‘I didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on me.’ But hope is deep in the American psyche, because what matters about myths and politics is not necessarily whether they’re true or false, but whether they have the capacity to move people and to compel people to believe them.”

Obama’s message of hope proved to be audacious – extraordinarily so. And it succeeded. “There were a lot of people in the United States, myself included, who never thought our lives would encompass an African-American president in this land where slavery existed for more than 200 years,” says Gerstle. “Daring to hope is sometimes necessary to push aside the world-weary realism – ‘Don’t these people know how the world works?’ – that can stymie bold thinking and action. Obama’s combination of fierce intelligence and audacious hope stirred Americans to give him two terms in the White House. That resulted in eight years where all the kids of colour in America were growing up in an environment where the highest office in the land was held by someone who looked like them. Think of the kind of inspiration that can generate.”

As former Archbishop of Canterbury (and a seasoned campaigner), Dr Rowan Williams is very familiar with being told that he has no idea how the real world works. “I don’t claim expertise, but I do think there’s a role for ill-informed moralists from time to time!’ he says. “Why should I take for granted how the international financial system works, for example? Why should I assume this is a law of nature? Perhaps it is a good idea to ask: do we want to be locked into this? And if we don’t, what can we do about it? Just raising that question is a sign of hope.”

Hope is, of course, one of the three theological virtues in Christianity – the other two being faith and love. Williams sees hope as “not regarding any situation as closed down. There’s the sense that the triad of trust, hope and love is what our humanity ought to be growing into. And that means a certain amount of effort: not to be conquered by cynicism, despair or selfishness.”

It’s not about how things can only get better, he points out – indeed, bits of the New Testament suggest that things are probably going to get worse. “So what if things get worse? Do I then give way to despair? No, because even if things get worse, they can’t close down the possibility of change. So that’s why I think hope can survive a lot of practical disappointment. Because it has. Every generation has a reason for not being hopeful. But if you don’t resist, nothing will happen.”

So can hope help us when faced with monumental problems such as climate change? In the environmental context, hope isn’t naive: it can be a direct challenge to authority, says Balmford. “There are an awful lot of vested interests that don’t want things to change very much. Celebrating successes, through events like #EarthOptimism, and being far more ambitious about what we can achieve in addressing underlying environmental problems is really uncomfortable for some people.” And that means that the millions worldwide who joined the recent climate strike do count for something: it’s easy to forget that, in August 2018, that mass movement consisted of an unknown Swedish teenager sitting on a pavement with a cardboard sign.

When it comes to climate change, it suits a certain narrative, Balmford points out, to say that everything is hopeless because the Chinese are still building coal-fired power stations. “These things are, of course, important, but they don’t address the question: if I do something, will I make a difference? And the answer is: yes. It may be a modest difference. But it still counts.”

He sounds a note of caution, however: hope is good, as long as it’s the right sort of hope. “That small thing we do, that doesn’t mean we’ve done our bit. You can’t give up plastic drinking straws and think you’ve solved climate change. It’s a start. It makes you feel better. Now ask: what can I do next?”

There is a techno-utopian idea that capitalism will solve the problem for us, without any need for fundamental social and economic transformation. That seems to me the kind of hope that we need to resist

Certain kinds of hope can certainly be dangerous, agrees Duncan Bell, Professor of Political Thought and International Relations, because they can lull us into a false sense of security. “Anthropogenic climate change is going to be the major political challenge facing humanity and, in that context, hope is vital, but the hope can’t be mindless,” he says. “I worry about the techno-utopian idea that capitalism will generate technologies that will solve the problem, without the need for fundamental social and economic transformation. That seems to me the kind of hope that we need to resist.”

But having high hopes can spark change. Bell points to the late 19th-century burst of utopian thinking, sparked in part by the publication of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887 in 1888. Many 19th-century literary utopias, including those that followed Bellamy’s vision of a world with no private property, crime, money or lawyers, differed in one vital respect from those of earlier periods. “In the past, utopias were rarely thought of as realisable,” says Bell. “They were held up as mirrors to reflect on the existing society or models of ideal worlds. But many 19th-century utopian writers were convinced that their visions of Utopia on Earth were possible and could be brought about through collective action.”

In fact, Bell points out, many of the specific proposals of 19th-century utopians were achieved during the 20th century. “The NHS, for example. The modern welfare state. The beginnings of social and political equality between men and women. And these were all realised without recourse to any of the deeply unpleasant strands of this style of thinking, such as eugenics. The hope that we can mobilise sufficient social change to restructure the system? That kind of hope seems effective to me.”

And if you feel that all hope is lost, take heart. It’s fine to cry and scream at the injustice of the world. But pick yourself up and move on, says Remes. Recognise the things you can control, and the things you can’t, and hope will return. “After the wave passes, after all of this passes, it allows you to become stronger and more resourceful. Setbacks and challenges in life can make us more resilient. They can strengthen bonds with those around you. You shift the way that you see the world and what is important to you – and unimportant things start to fall away. Your connections with others become more meaningful.”

Ten years ago, at Lakenheath, a lone pair of cranes joined the bitterns. There were no projects to attract them or funding to find them: they found they own way. Cranes haven’t bred in the Fens for four centuries. Now, around 40 cranes have made the wetlands their home: you can see flocks of them skimming across the sky at dusk. “I’ve heard it in the chillest land / And on the strangest Sea,” Dickinson’s poem concludes. “Yet, never, in Extremity / It asked a crumb – of Me.”

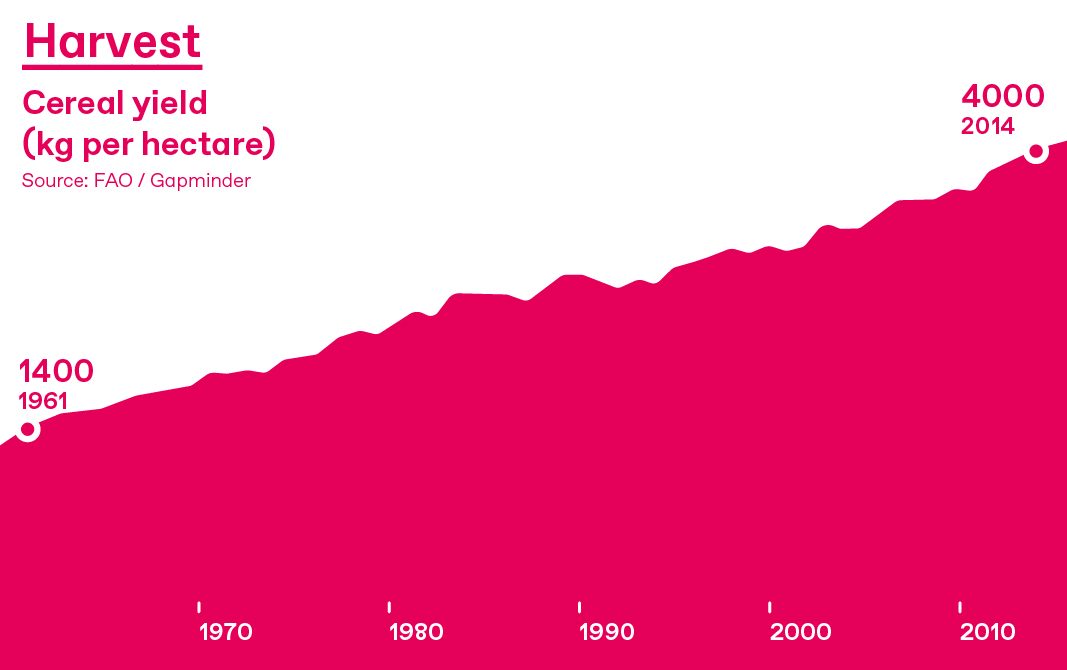

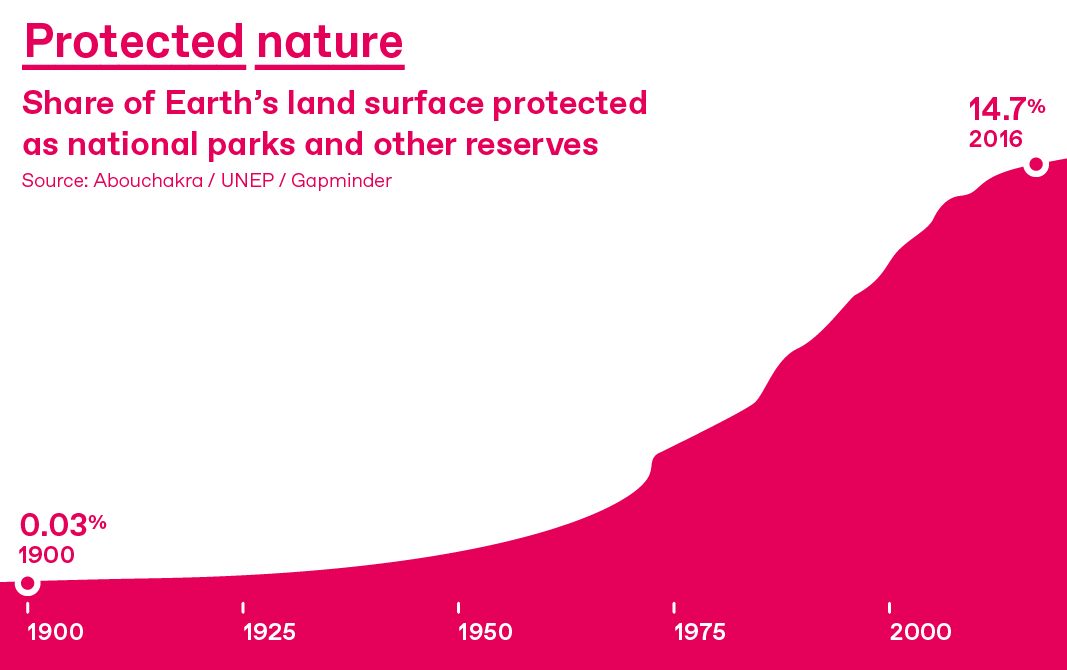

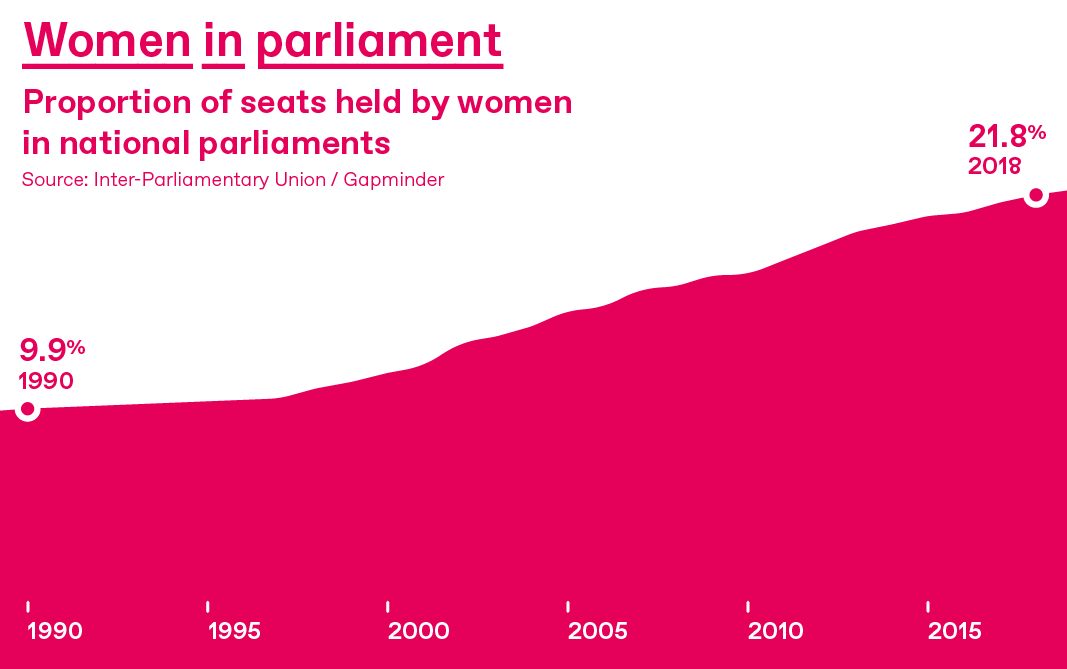

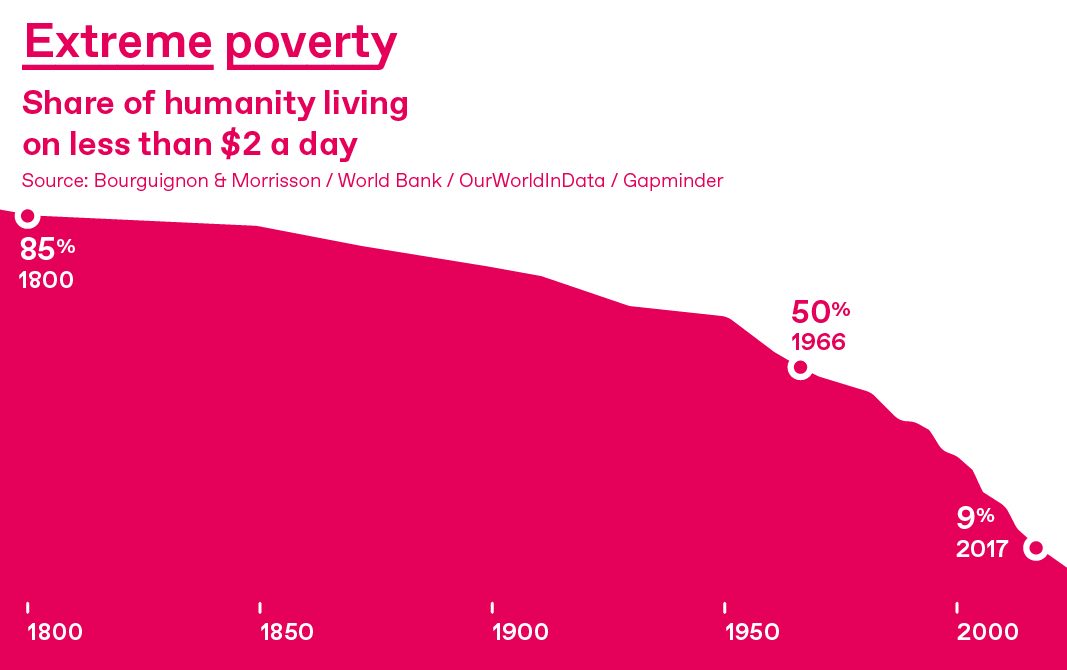

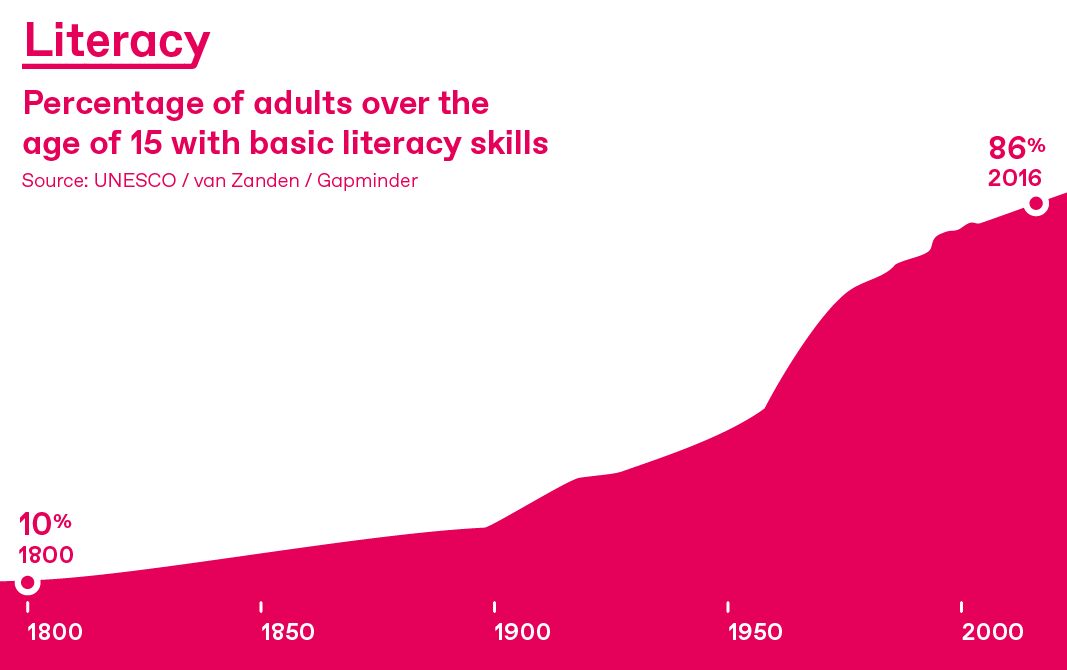

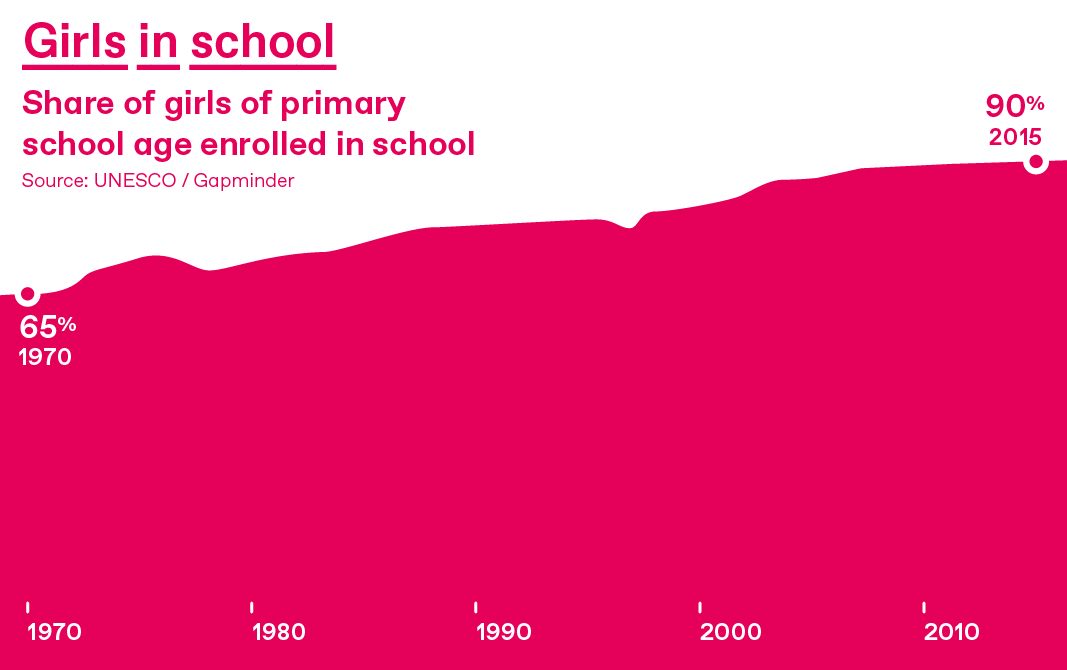

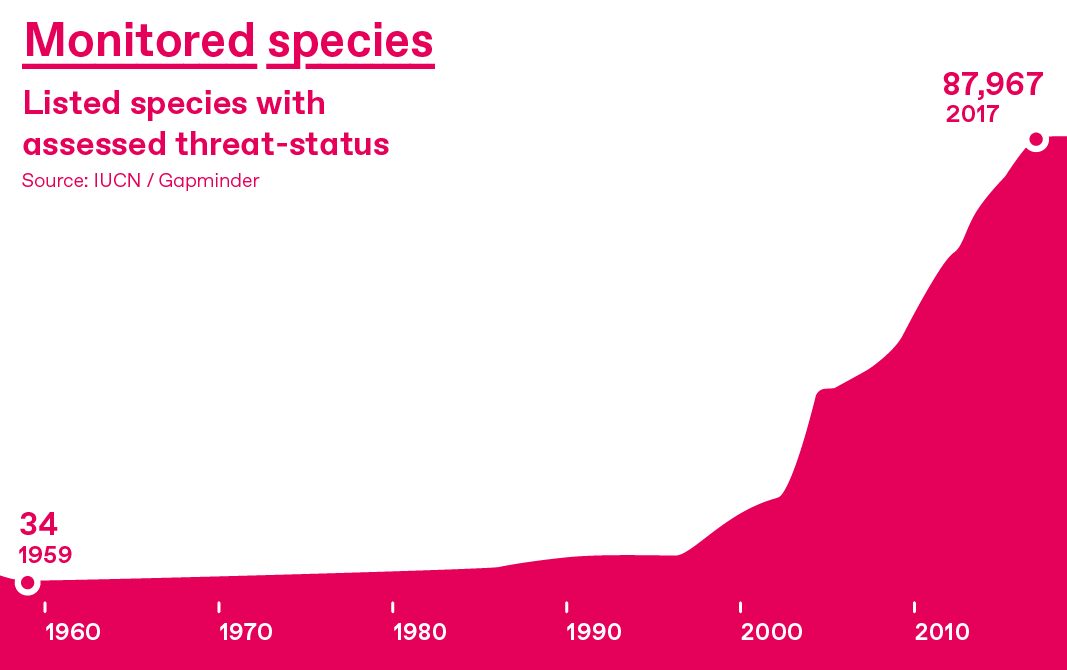

Gapminder: The graphs on these pages have been created from data collated by Gapminder, an independent Swedish foundation established to promote a fact-based worldview. Gapminder’s data is made available for use for free, by everyone, under a Creative Commons licence.