How to be Modern

Why do students want to decolonise their curricula? And what does it have to do with the rest of us?

Climate change. Technology monopolists. Artificial intelligence. The rise of China. An increasingly mercurial US. Resolving the problems of the 21st century requires fresh thinking – and well-informed thinkers. So it will come as no surprise that, in Cambridge, curricula are under review as academics aim to give students access to the widest range of ideas and thinkers, as well as the analytical tools they will need to shape their world.

However, over the past few years, this quest has become more searching, and in some ways more painful. Because, at lectures, discussion groups, and at Hall and in the library, the work of ‘decolonising’ the curriculum has begun.

You may have read about it in the newspapers – perhaps accompanied by a headline blaming ‘snowflake’ students who want ‘diversity’, or maybe alongside reports that academics are busy throwing away the canon in favour of new and unfamiliar writers and thinkers. Out with Shakespeare, Milton, Plato! In with non-white authors from around the world! (CAM readers will be unsurprised to hear that this is not actually the case, of course.)

And it would be funny, except that decolonising the curriculum is important, exciting and invigorating. It has got academics thinking about the most important thing they do: thinking about thinking. But it is can be painful, challenging and slow. It deserves to be better understood. So if you have ever wondered why students around the world are protesting about their curricula, why it has made some sections of the media so very cross, and what on earth it has to do with the average Cambridge undergraduate – or graduate – please read on.

At its heart, ‘decolonising the curriculum’ is a rather blunt way of describing a way of thinking about what we know, and what that knowledge might mean. Like postmodernism at the end of the last century, ‘decolonisation’ offers the inquiring mind a new lens through which to assess the world, as Toni Fola-Alade, former president of the African Caribbean Society explains. “For me, it’s about making the curriculum as inclusive and reflective of all the students as possible and reappraising what we collectively value and what’s important,” he says. “That’s not necessarily demoting the individuals who are already in the canon or on the curriculum. It’s thinking about how values and communities change over time, and ensuring the curriculum reflects that.”

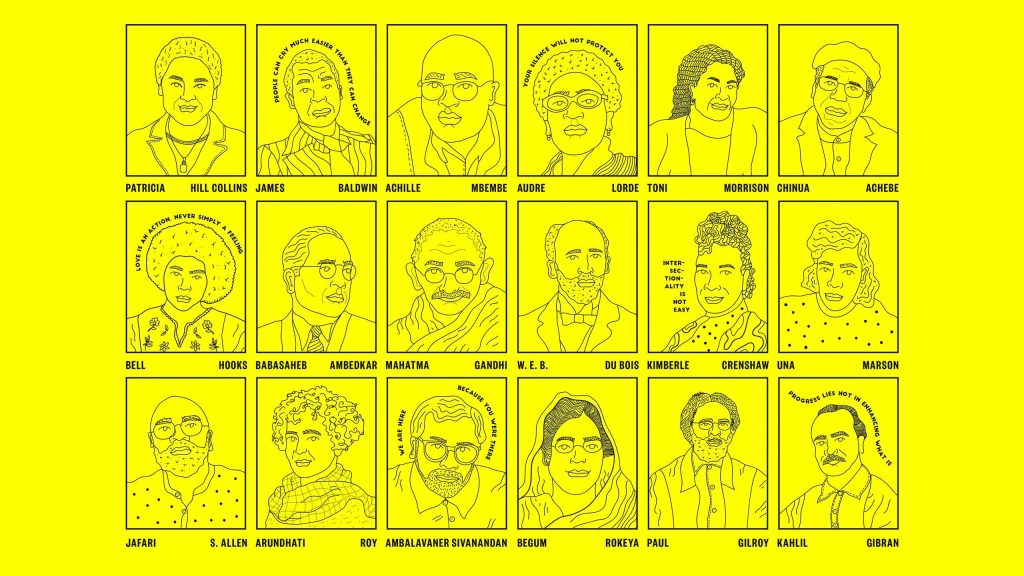

It is also important to say what decolonisation isn’t. “One of the most harmful myths about decolonisation is that it’s getting rid of all the white western scholars from the reading lists,” says Dr Ali Meghji, Lecturer in Social Inequalities. “This is not about pointing fingers at anyone, or blaming people. We’re saying, look, these things – empire, colonialism, imperialism – happened. And because context shapes academic knowledge, why don’t we apply that context to colonialism, imperialism, enslavement and empires?”

Other perspectives

And that matters because students want to grapple with big issues: Brexit, immigration, Trump, racism, the culture wars. In the last century, a solid grounding in national history and western philosophy would have been more than enough to get by. But in a global, hyper-connected world, where cultural nuance can wipe billions off a company’s value or start a war, some knowledge of other cultures is helpful – but an awareness that yours is not the only way of seeing the world is absolutely crucial.

Students deserve access to all the intellectual firepower academics can give them

Which is why, says Reader in Sociology Dr Manali Desai, they deserve access to all the intellectual firepower academics can give them. Why should her students not benefit from reading Ambalavaner Sivanandan and John Berger alongside John Locke and Max Weber? “I want to open up a space in which they can consider questions of identity and self in new and productive ways,” she says. “If that sounds rather too theoretical, try this: would the Home Office have avoided the embarrassment of the Windrush crisis – in which citizens of the British empire were deprived of their British citizenship – had they been familiar with Sivanandan’s bon mot: ‘We are here, because you were there.’ I like to think it would.”

Indeed, recognise that a universal theory is not universal, and whole new avenues of possibility open up. For example, Michel Foucault is widely taught in sociology, philosophy, social sciences and history. “Foucault argues that there’s this moment in history where punishments such as execution stopped being public – instead, people are hidden away in prison, or controlled by soft forms of surveillance,” says Meghji. “And that’s true in some parts of the world. But Foucault is talking about French society – at a time when executions were exactly what the French were doing in their colonies, such as Algeria. Why does Foucault say that his theory is universal when it is so easily refutable? Because, until recently, it was easy to think that you can universalise from the particular experiences of just a few countries and societies.”

The decolonisation of curricula may make sense, but it can also be surprisingly difficult. The word itself, says Fola-Alade, “is quite ominous. It sounds big and threatening.” When Desai reads angry headlines, she says that she senses a feeling of threat. “Making the effort to question my long-held, painstakingly researched intellectual positions is challenging. At least in my case, it’s my job. For example, I had to question how, despite being a woman of colour, I had internalised my class and caste privilege. I had to – and still need to – approach thinking about race by questioning my own comfort zone.”

Dr Mónica Moreno Figueroa, Senior Lecturer in Sociology, points out that it is easy to feel defensive when confronted by the ideas that fuel decolonisation, and that’s fine. “You will have to understand that the value of what you know is, so far, insufficient – and not take that as offensive,” she says. “It doesn’t mean that what you know is not good. It means it is limited. I think that’s uncomfortable and threatening – in the sense that we don’t know exactly what is there on the other side of the western perspective. But I believe that confirming our place in the world, and what we already know, is not the objective of producing knowledge. It’s not that those of us in favour of decolonisation are saying: we don’t want your knowledge. What we are saying is: we want you – and all of us – to have

more knowledge.”

It involves, for many of us, a completely new way of thinking, as Desai explains. “When you put yourself, your people and your categories of thought at the centre, others are, by definition, at the margins. They can be brought in as bits of exotica, to look at with curiosity, but can never be an opportunity to re-examine or interrogate your own assumptions.”

Is this going to hurt?

Fola-Alade is studying Human, Social and Political Sciences (HSPS), giving him an insight into how changing the focal point can enable academics to get a much clearer understanding of how human societies – globally – really work. “Take the process of state formation,” he says. “The traditional account of state formation uses a European model to discuss how war centralises big states in order to collect tax more efficiently. But when you look at how state formation occurs in China, Latin America or Africa, you get a very different picture. The European view is the one used as the universal model – yet it’s not universal.”

This kind of thinking can have very real consequences. Take climate change, for example: to manage this kind of unprecedented challenge, it is crucial to realise that yours is not the only way of doing things. In Cambridge, Desai says, much discussion focuses on how to reduce, reuse and recycle – how to continue as we are while making less impact on the Earth, and, via the Kyoto Protocol, to encourage the rest of the world to do the same. “It is therefore fascinating to discover how this approach, far from being universally accepted, is actually unique to western modes of thinking,” she says. “In other places in the world, indigenous communities continue to maintain different forms of thought, built on different assumptions about nature. As we contemplate the possibility of environmental catastrophe, it makes sense to examine the fundamentals of how we got here – and how we could do things differently.”

In a global hyper-connected world, where cultural nuance can wipe billions off a company’s value or start a war, some knowledge of other cultures is helpful – but an awareness that yours is not the only way of seeing the world is absolutely crucial

Two years ago, Desai, Dr Arathi Sriprakash (Education), Dr Adam Branch (Politics) and Dr Moreno Figueroa organised a series of exploratory seminars at CRASSH on the subject (Towards a Decolonised Curriculum in Cambridge: A Draft Manifesto). Demand was huge. Many departments have now set up working groups. Academics, and particularly Part II students, are working together to think deeply: about their subject content, about their analytical tools, about the future. Already, many departments have revised their curricula, and others are following, using formal and informal meet-ups, teach-ins, working groups and seminars in both specific subject areas and more widely across the University.

What’s next?

First, don’t be afraid to get involved, says Fola-Alade. He explains: “These issues are wide-ranging. They are not reserved for those who deem themselves activists. Of course, activists do a lot of the work pushing the decolonisation movement forward, and deserve a lot of the thanks and the praise. But students and staff could be argued to be part of the decolonisation movement if they are doing any kind of work that seeks to make the University a more inclusive and accessible place.”

Meghji says he would like to see more knowledge exchange: pointing out that the knowledge that is valued tends to come from institutions in the global north. “You could sponsor visiting academics from universities in the south, and work towards ways to increase awareness of the knowledge they produce, giving a platform to people who are doing excellent work,” he says.

Happily, all is not lost for those of who left university many years ago. Simply reflecting on your own experiences and knowledge can be illuminating, suggests Moreno Figueroa. “First, think for yourself. What are you missing? What have you missed in your own education. And from there: what do you wish for the younger generations?”

But don’t look for a final word on decolonisation: it is an ongoing process, not a means to an end, and there is no manual. “Sometimes I am asked if I have an end in mind, a time by which the curriculum will be ‘decolonised’. I have to say that the answer is no,” Desai says. “Once you start to change your perspective, many other issues come into focus. So, for me, decolonisation is not about who is ‘in’ or ‘out’ on a reading list, but rather about an opportunity to broaden our perspective and, hopefully, gain deeper insight and understanding.”

And, in the meantime, despite the media brickbats and misunderstandings, she says she is very glad to be working on this now. “To be part of the generation that gets to engage with these issues is a privilege. Because the debate and the discussion have given a vibrancy to academic life: people are thinking about the essentials – what we teach and think, and why – and that’s an incredibly exciting place to be.”

The Global Humanities Initiative: collecting the world through culture

The new Global Humanities Initiative aims to develop innovative approaches to teaching and research in the broad range of subjects that make up the School of Arts and Humanities. From religion, language and history, to art, architecture, literature, film, music and the study of the digital world, it will bring our community into dialogue with voices and viewpoints from around the world.

Through the initiative, we will create the links, internally and externally, that will positively influence what we teach, what we do, and who we are. These connections should grow organically from the bottom up, led by academics who understand implicitly how their areas of study need to grow and how they would benefit from wider thinking, as well as what their students want to learn about.

Universities should reflect the communities they serve, and the Global Humanities Initiative will ensure that Cambridge does that, holding a lens up to all cultures to promote better understanding and create important new connections.