Privacy. Democracy. Freedom of speech. Anonymity. Access

Privacy. Democracy. Freedom of speech. Anonymity. Access. Technology – from data to social media – is forcing human rights into the spotlight

Data has become a ubiquitous – yet almost imperceptible – part of our daily lives. Every one of our interactions with technology, from tapping a debit card in a convenience store to liking a Facebook post, adds to the near-limitless store of information generated by and about us.

Dr Sharath Srinivasan, co-director of the University’s Centre for Governance and Human Rights (CGHR), likens it to a dense but invisible fog. “We don’t see it, but it’s there and always being produced by our intended and unintended efforts,” he says. “And the fog ends up sublimating into something that, in terms of seeing patterns, can be analysed, shaped, bought and sold in ways that allow for possibilities we can’t even imagine. Those patterns are then used to make decisions that affect us.”

Digital technologies control, blur and fragment a whole process through which judgments are made about our lives that can have a bearing on our freedom, our agency, how we understand our place in society and how others understand us. And they impact greatly on our human rights – both positive rights such as freedom of speech and association, and negative rights such as freedom from harassment, intrusion of privacy and even violence.

The top four or five largest companies in the world are involved in the commodification of personal data. There’s no way we can’t think about the role they have

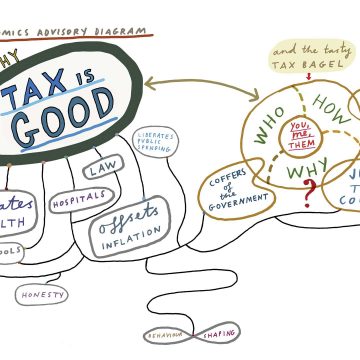

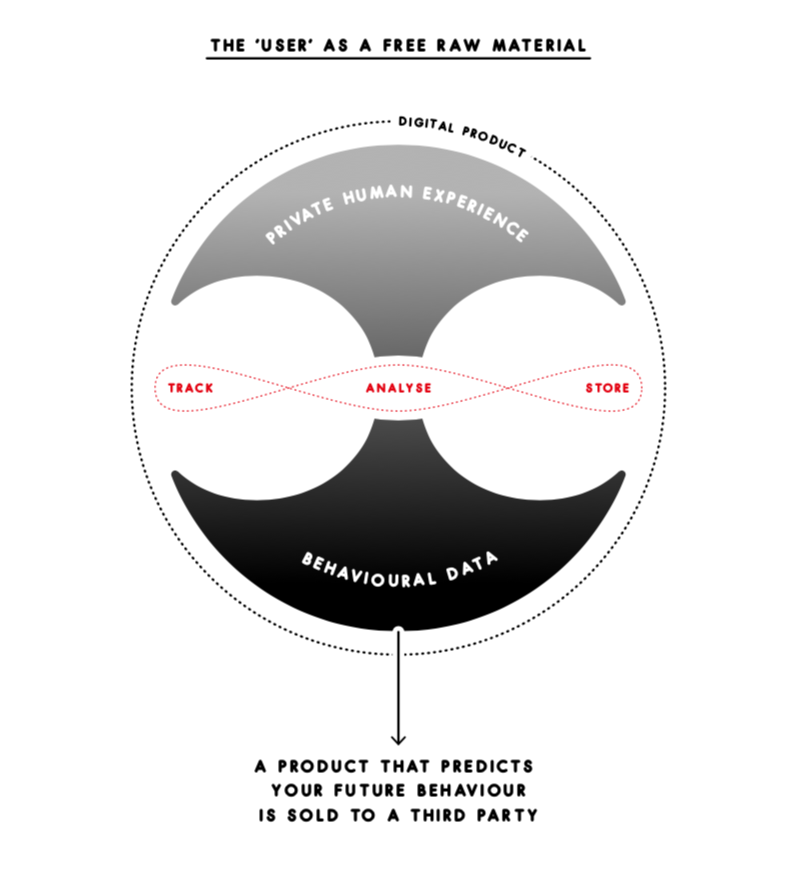

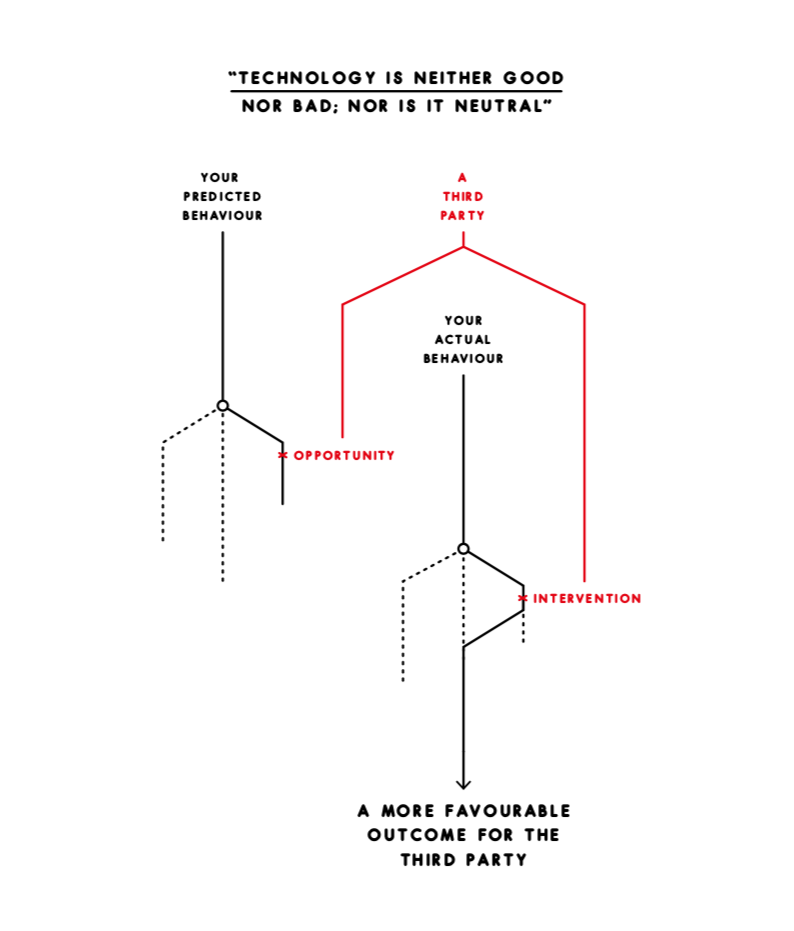

The business model underpinning all this has been characterised as ‘surveillance capitalism’ – a term popularised by the Harvard Business School academic Shoshana Zuboff. It’s a framework in which the complex of tech leviathans such as Google and Facebook “unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioural data”, and generates profit by turning it into “prediction products” that can be used to sell products, change markets and potentially influence elections.

Rebekah Larsen (St John’s, 2014) is a PhD researcher at the Sociology department who has worked on digital rights and privacy topics with CGHR. She says: “If you look at market capitalisation, the top four or five companies in the world are involved in the commodification of personal data. There’s no way we can’t think about the role they have in the way we understand human rights.”

It’s a far cry from the optimism of the early 2010s, when social media platforms were hailed as neutral facilitators for citizens seeking to assert their rights – most notably in the news narratives surrounding the Arab spring.

Dr Stephanie Diepeveen, a post-doctoral research associate at CGHR, has been examining the ways in which Kenyans engage in discussion of politics on Facebook. Her work suggests that the platform itself affects the conversation in some unpredicted ways.

Entrenching mindsets

“There was an assumption that, when we speak online, we’ll be freer with what we say because there’s this physical distance, and we have this digital avatar personhood through which we speak to others,” she says. “That did happen; but we found this distancing also made people revert to their entrenched beliefs and familiar tropes – ‘common sense’ – to explain what was going on in politics. So, contrary to expectations, it wasn’t really changing mindsets.”

To support freedom of association and other fundamental human rights, Diepeveen believes that online spaces need to be more suited to open discussion. “How do we preserve a space where there’s freedom for people to speak to one another in ways that don’t have foregone conclusions?” she asks. “A lot of the concern focuses on the way platforms such as Facebook are using our data to try to predict and shape our future behaviour. How do we prevent that and retain the unpredictability in politics?”

But despite the difficulties, Dr Ella McPherson, co-director of the CGHR, believes that researchers will still need to engage with the big media platforms. “It’s a real tension that the human rights community feels,” she says. “These platforms are where people are already communicating, so there’s a real impetus to maintain relationships with them. At the same time, how can you trust these companies on human rights matters when it’s clear that they have a very self-serving relationship with the concept? We’ve seen this with surveillance capitalism, and all the data-hungry mechanisms by which they make their money.”

So is it possible to regulate the digital realm while protecting and enabling the new democratic possibilities that it affords? Dr David Erdos, Deputy Director of the Centre for Intellectual Property and Information Law, believes that the prevailing wind is now behind more robust policing of digital spaces.

Duty of care

His research looks at whether regulation could be effective in upholding citizens’ rights online – combating violations like cyberbullying, harassment, and extreme infringements of privacy such as revenge pornography.

He says: “It may be successful in tackling all this, but it will depend on a degree of monitoring and management of online content beyond what we’ve seen to date. We’d be talking about a duty of care that managed platforms would have. Many activists see that as potentially an infringement on the privacy of users who may want to remain anonymous and unregulated.

“Europe has always had an approach that stresses the state’s responsibility to protect rights, not just to be a nightwatchman. We have existing legislation – notably the whole data protection framework – where the state has decided to intervene in a strong way. The laws threaten companies with four per cent of their annual global turnover, which can mean hundreds of millions of euros in the case of Facebook or Google.”

Within the EU, the totem of data protection is the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which imposes one of the strictest such controls of any democratic jurisdiction – and it has brought debates concerning the balance between freedom of speech and privacy into sharp focus.

Erdos says: “You can’t really move digitally without being impacted by the GDPR. If you take the law seriously, it encroaches on people’s rights to associate, to run a business or start a club – right down to one person trying to manage a choir. It’s rather a mess, and that’s before you go into questions of how you enforce it. With sites outside EU jurisdiction, in the US, Russia or China, can you enforce it? When should you reach over and say, ‘Because you have an impact on our citizens or residents, we have the right to regulate you’?”

If we embrace the notion that personal data is a commodity to be traded, we lose a very important part of what privacy means both in social terms and in the way it helps us develop as individuals

Within Europe, the so-called right to be forgotten – permitting individuals in some cases to demand that Google and other search engines “de-index” material that includes their personal data – has proved particularly controversial. Media outlets overwhelmingly presented it as a threat to freedom of expression and an example of state-endorsed censorship. Larsen, who solicited the opinions of journalists across the broadcast and print media, says: “It was a sticky case for them, because many saw it as an instance where editorial privileges were being taken away from them by the EU. But many of my interviewees reported that they couldn’t help thinking they may have been primed by platform providers to react in this way.”

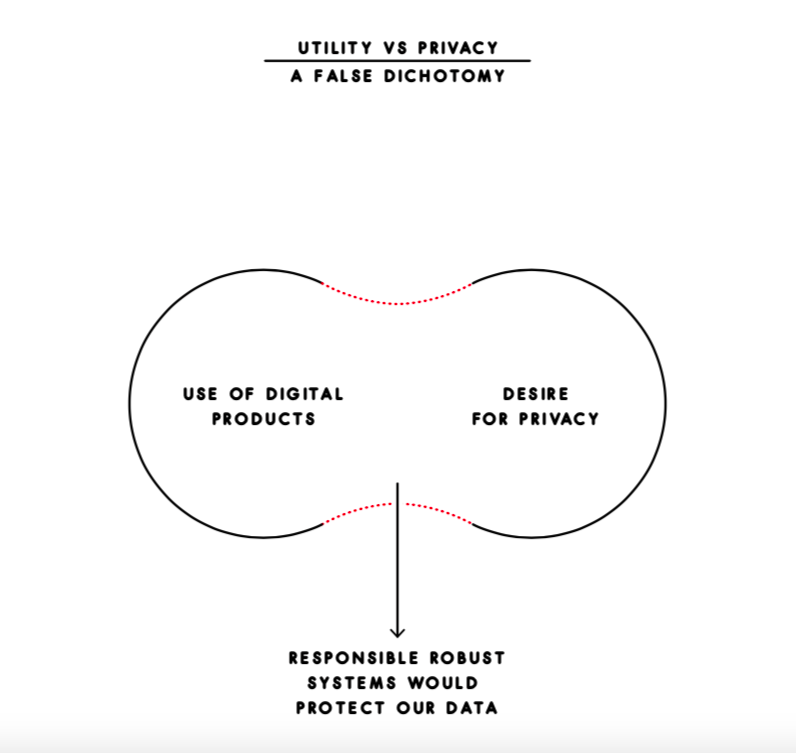

More broadly, Larsen believes that these initiatives are not necessarily challenging the larger assumptions that frame the debates around digital rights – such as on the ownership and monetisation of data. As an example, she recalls her involvement in a project for the European Commission while completing her MPhil at Cambridge Judge Business School. “We were looking at ways to give people more control over their data,” she says. “However, if we embrace this notion of personal data being like a commodity that can be traded, I think we lose a very important part of what privacy means in social terms, and the way it helps us develop as individuals. And it can entrench existing inequalities: people who have fewer resources would be more likely to sell their personal data. You can end up with a very neoliberal version of human rights that actually supports the practices of surveillance capitalism.”

It is a sentiment that chimes with broadcaster and author Jonnie Penn (Pembroke 2014), who is a project lead at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence and is completing a PhD on the political history of AI. He says: “Historians of technology talk about ‘technologies of control’ like digital computing. In the west, the public have seen these tools – at least until recently – as affording us all sorts of new opportunities and benefits. Now, I think they’re starting to awaken to the fact that, in the wrong hands, there’s serious room for abuse.

“That’s why we’re talking about digital rights, because we need to rebalance the whole equation somehow. My worry is that if we re-centre this around the individual, a kind of neoliberal conception of an individual’s rights, we risk devaluing the collective systems that are actually what are failing today. A good example is the environment: we don’t afford it the protections that we might for a human being. We risk peril as a result. Indigenous societies have known this for millennia.”

With a new economy that heavily depends on big data – and, increasingly, on artificial intelligence to process it – Penn believes that if collective protections are not brought in now, they will be exponentially more difficult to establish in the future.

Artificial intelligence can make it difficult to understand exactly where decision-making is taking place. It enables the policymaker to say: ‘Talk to the data scientists’

“I always use Central Park as an analogy,” he says. “There was a moment in the mid-19th century when the decision was taken to build this park in the middle of what became a metropolis.

“It would be a lot harder to do now – to knock on doors and say, ‘We’re going to demolish your building and put a park here.’ If we don’t affirm the collective good in our systems, the outcomes could be really awful. Our Central Park is a Just Transition to zero carbon: decent work, divestment, warming below two degrees – whatever it takes to keep our grandchildren from extinction.”

Real-world consequences

As artificial intelligence becomes more complex, the processes that drive its decisions become increasingly opaque and more difficult to scrutinise and hold to account. Where errors are made, the consequences can damage an individual’s quality of life, as in cases where social-media posts have been mistakenly flagged up as offensive, leading to a ban from the platform. And, as Srinivasan points out, the real-world consequences can be far more severe. Artificial intelligence has already been piloted in criminal justice contexts, helping to determine sentencing and parole decisions.

“Where do we point the finger if we want to say an outcome was a bad one?” he says. “Who is responsible? It becomes increasingly difficult to understand where the sources of the decision-making mechanics are located. The policymaker may just say, ‘Wait here – the data scientists analyse the data and come up with the algorithms that drive our decisions. You should talk to them.’”

Nevertheless, Srinivasan remains sanguine about the ability of digital technology to perform social good, and the role of institutions such as CGHR in bringing this about. He says:

“We know quite well that spaces such as Facebook and Twitter don’t lend themselves to the better qualities of democratic life. So where and how do new possibilities come about? The answer is, through innovation, and through public demand for digital technologies that enable the things that we still value and cherish in democratic life.”