This idea must die: the arts are less important than the sciences

The Vice-Chancellor, Professor Stephen J Toope, says we need to abandon the idea that the arts are nice, but not essential.

The idea that the arts are less important than the sciences is a zombie: scary, dangerous and apparently impossible to kill. And that matters, because it remains a shockingly powerful idea for a lot of people – it’s still very much alive.

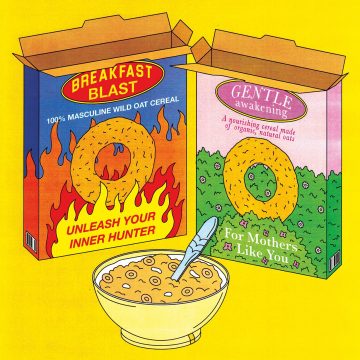

Why? Over the past 30 years, public policy has become increasingly focused on the ‘measurable usefulness’ of an activity, rather than on its inherent value. Of course, when there are financial pressures, people have to make choices, and it’s just a lot easier to count up the obvious benefits of science, technology and mathematics.

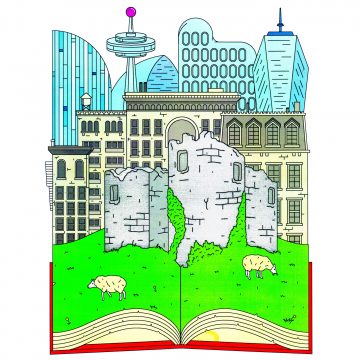

But that does not mean it is not possible. For example, tourists do not come to the UK to visit our great scientific facilities – even if I wished they did – but to see our architecture, art, theatre, music and culture of all sorts. The UK is not that big, but its cultural industries contribute a vast amount to the economy, and its cultural knowledge gives the UK tremendous soft power in the world.

But while I believe that the arts and humanities – especially in the UK – are an important part of our economy and should therefore be recognised as such by government, I also think that focusing solely on what you can measure underplays value. We saw this with Covid. If we don’t understand psychology, if we don’t understand history, if we have no basis for interpreting how people think and feel because we have only our own experience to go on, then we’re very likely to make mistakes or miss opportunities, whether that is vaccine rollout or designing a track and trace system.

Indeed, it’s not an ‘either/or’: we absolutely need the scientific discoveries, the vaccines, the treatments and the rest, but we also need people who can help understand how to make those function effectively in diverse societies. Take, for example, the digital world. Without law, ethics and storytelling, the digital public sphere becomes unusable. Similarly, right now, the newspapers are filled with debates about the ethics of artificial intelligence, how we treat memorials, and the notion of free speech. These are all right at the heart of the humanities, and they cannot be solved without the tools and information that the humanities give us, not least in helping us understand how we can talk with one another and debate in effective ways.

Culture is multifarious and multifaceted, and that’s why comparative cultural understanding and diversity of understanding is so important. There is no either/or. For example, our School of Arts and Humanities has been imagining what the humanities might look like in the future, working with partners around the world to effectively share our resource in the social sciences. We want to think about big-picture questions – the future of the human world and the human spirit – from a whole series of different perspectives, but drawing together insights from African, Asian, Latin-American and North American partners at other great universities – no single university can capture the entirety of human knowledge.

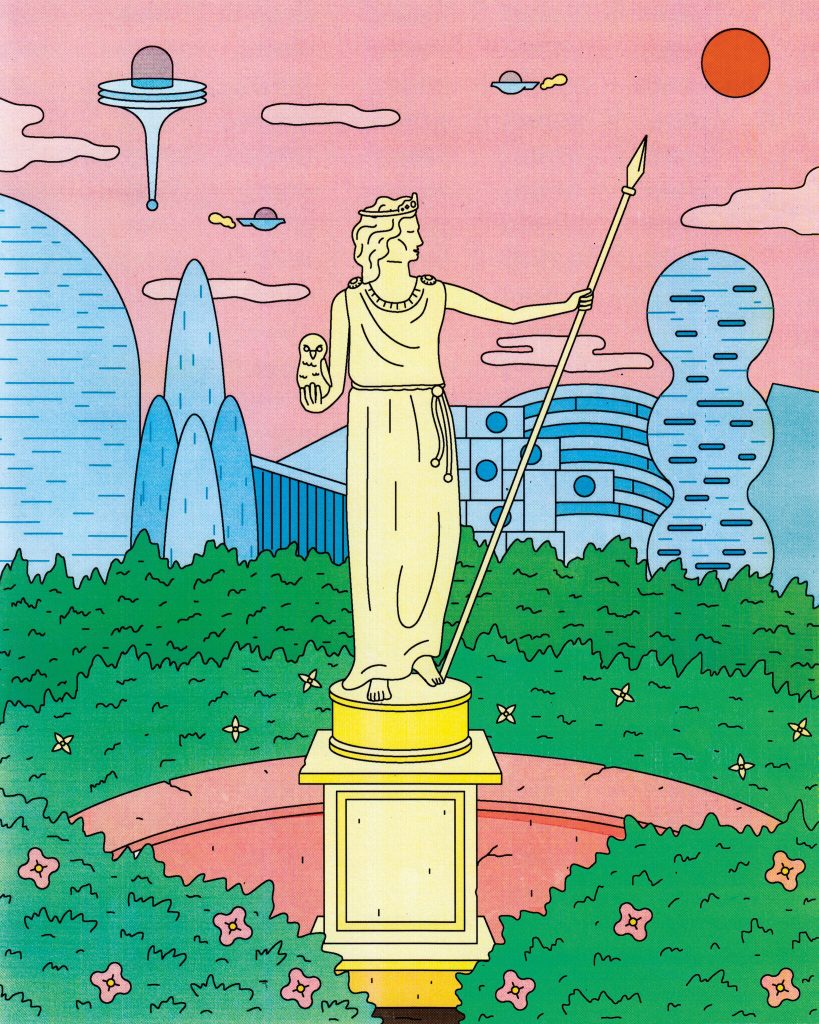

Every person has to have some sense of who they are – where they come from, where they’re going – and that’s about implicit philosophy, implicit ethics and implicit cultural inheritance. I’ve always thought that we have to be careful not to fall into the trap of thinking that everyone is the same underneath – indeed, my experience is that people are actually quite different. The humanities is the space in which people think hard about, and endeavour to gain greater understanding of, themselves and others, and that seems really important to me.

Critically, the humanities help us understand humans and humanity. We do this in myriad ways, through poetry, through philosophy, through history, through psychology and law, and so on. I just can’t imagine a world in which we don’t care about those things. And this knowledge, just like that of the sciences, is priceless.

To further the dialogue between the School of Arts and Humanities and voices and viewpoints from the broader community, Cambridge has launched a new Global Humanities Initiative. The initiative aims to develop innovative approaches to teaching and research, and create the links that will positively influence what we teach, what we do and who we are.