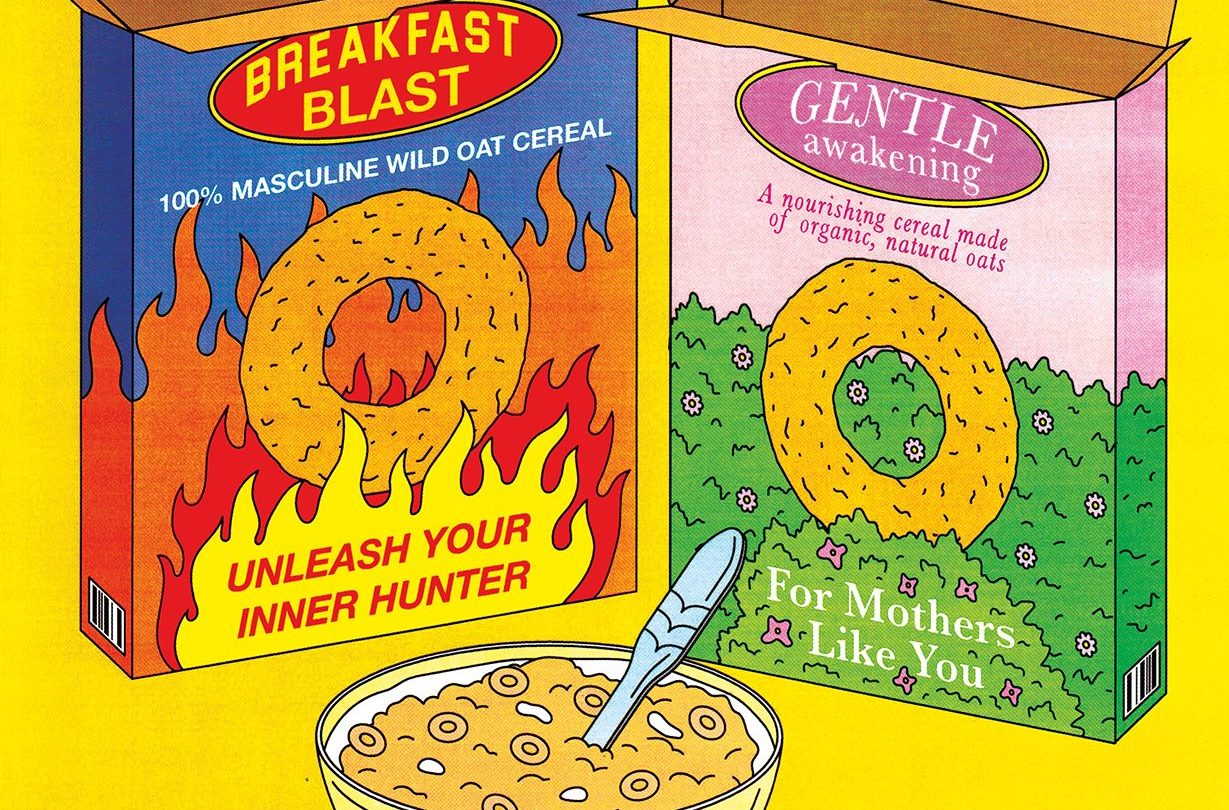

This idea must die: ‘Gender roles are universal’

Dr Sheina Lew-Levy explains why the idea of universal gender roles just isn’t supported by the evidence.

We often hear people justifying gender roles as innate and stemming from our roles as hunters and gatherers in the past. However, gender roles among hunter-gatherer societies today are much more diverse than most would assume. Studying child development in these societies can help us understand the role of biology and culture in shaping children’s gendered behaviours.

I study child development in hunter-gatherer societies. Hunter-gatherers are culturally and geographically diverse, speak different languages, and rely on different resources for subsistence. However, they share several foundational values, including very high gender and age egalitarianism, and high rates of inter-household sharing of food, space, knowledge and other goods.

These cultural patterns translate to several shared childhood experiences. In particular, hunter-gatherer children are afforded extensive autonomy to learn and play as they see fit. In fact, much of children’s time is spent in the playgroup, where they feed themselves and emulate aspects of adult culture in their play. For example, children will frequently play ‘camp’, building small huts and hearths, and cooking small portions of food to be shared with playmates.

We know that mothers tend to be the primary caregivers in all societies. But, the second or third caregiver varies a lot.

A majority of my research has been conducted among the Hadza of Tanzania and the BaYaka of Congo. The Hadza rely on honey, baobab, tubers, berries and meat hunted with bows and arrows. The BaYaka subsist on fishing; hunting with spears, guns and traps; tubers; insects; honey; and small gardens. In both societies, the majority of food comes from the forest or bush. For both, like other hunter-gatherers, there is a clear, gendered division of labour, but it’s not the case that men necessarily do the hunting and women do the gathering. In fact, while Hadza men are solely responsible for hunting, and Hadza women do a majority of the gathering, BaYaka of both genders take part in both hunting and gathering, though to varying degrees.

Cross-cultural variation in adult gendered work may explain the differences we observed in children’s gender-typed play. Take doll play. In the west, girls consistently play with dolls more than boys. Among the Hadza, we also found that girls participated in more doll play than boys. But among the BaYaka, boys participated in doll play just as much as girls. Why?

We know that mothers tend to be the primary caregivers in all societies. But, the second or third caregiver varies a lot. Sometimes it’s sisters, grandmothers or fathers. BaYaka fathers are considered some of the most involved in the world. Thus, our findings suggest that children are watching and learning from potential models of their own gender. For the BaYaka, this involves boys emulating fathers in carrying out childcare. In other words, while who we pay attention to may be gender-specific, what we emulate is culturally specific.

Context also changes how gender-specific behaviours are expressed. Hunter-gatherers tend to live in camps of 25 to 75 people. In such small settlements, finding playmates of one’s own age and gender is rare. As a result, children spend much of their time in multi-aged and mixed-gender groups. In fact, we found that children in larger camps were much more likely to segregate into same-sex groups than children in smaller camps.

While rough-and-tumble play is usually considered a predominantly male activity in most societies, our findings suggest that both boys and girls allocate similar amounts of play time to rough-and-tumble, at least until adolescence.

Since children play in mixed-gender groups, it’s likely that children adjust their energetic play styles to those of playmates of the opposite gender, essentially meeting in the middle in terms of gender-typed play.

While many studies suggest that aspects of gender-typed play and gender-segregation during play are widespread, human development always occurs within a cultural context, and this context can mediate the degree to which gender-typed behaviour is expressed. While a majority of psychological studies are conducted in the west, opening up our field of research to include people from more diverse backgrounds, including hunter-gatherers, can give us a much better view of the diversity of human experiences.

Find out more about psychology at Cambridge.