This idea must die: Grammar schools are a tool in promoting social mobility

Professor Peter Mandler says schools cannot compensate for years of different life chances – and, anyway, that’s not their role.

During the post-war period there was huge social mobility. And there were grammar schools. Therefore, the grammar schools must have caused the social mobility, right? Well, no. That’s just mistaking correlation for causation.

No new grammar schools have been built for decades, and that’s mostly because parents rejected them and sociologists proved that they didn’t work. They proved that there’s no correlation between school type and career trajectory. Even by the 1960s, most local authorities, even Conservative ones, had dropped grammar schools. Yet the idea persists that grammar schools were good for social mobility.

But let’s think about what social mobility means: moving from a lower to a higher occupational class in society. During the 1940s to the 1970s, and particularly the 1950s and 60s, more than 50 per cent of the population moved to a class higher than their parents’, mainly because the boom in the service industry created a lot of white collar jobs. So people moved from blue collar to white collar jobs. Working class kids had the potential for greater upward mobility, since middle class and upper class kids were already nearer the top of society.

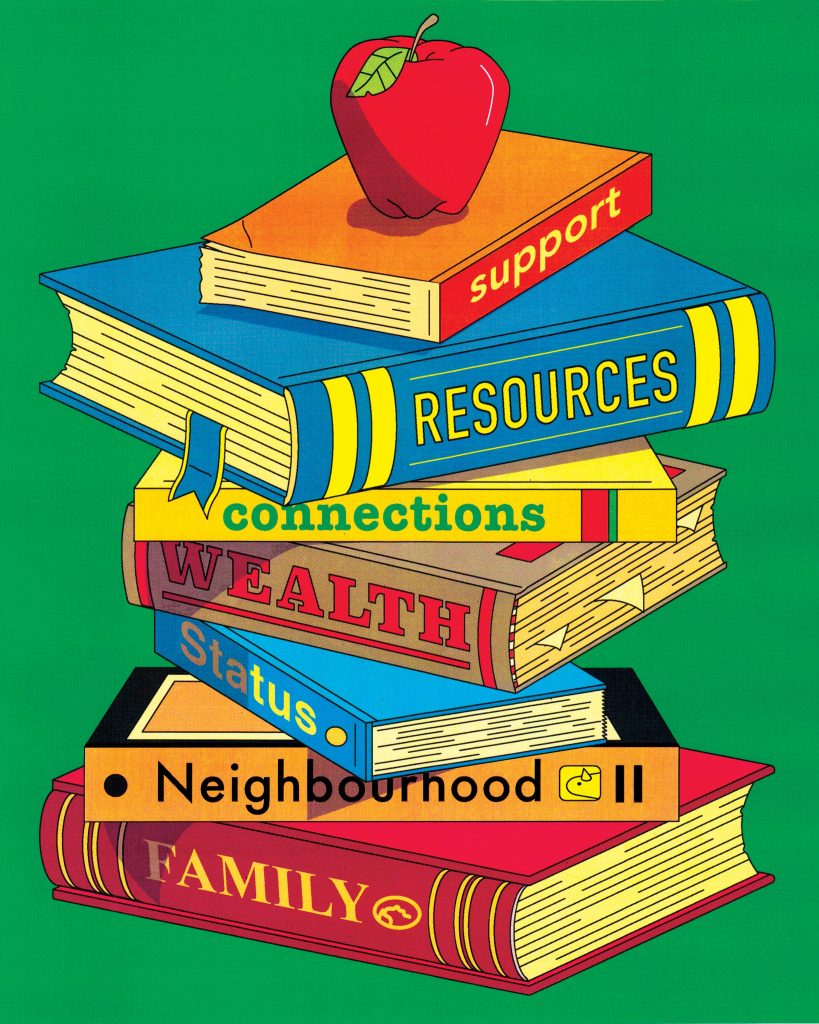

So what role did grammar schools play? We need to start by looking at exactly who went to grammar schools. Most working class kids did not pass the 11+ exam and,of those that did, many left at 15 or 16. Around 90 per cent of working class kids didn’t go through grammar school. Passing the 11+ and staying at grammar school depends on lots of things working class kids did not have: support at home, resources, even interest in what feels like an alien land. So most working class kids didn’t do O Levels; fewer still went on to A Levels and higher education. Education was not what was advancing them in society.

Sociologists agree, therefore, that grammar schools did not increase social mobility, but neither did comprehensives. Since the 1970s, social mobility has been declining but much of that is due, again, not to education, but to changes in the jobs available – or the lack of changes. Middle class and working class kids today have the same educational experience, and yet the middle class still go into the top-paying jobs. One study showed that 30 per cent of people from Class 1 backgrounds leaving school with no educational qualifications nevertheless ended up in Class 1 jobs. It seems your class position is, mainly, inherited.

We would do better to focus on schools making kids happier and healthier, with strong academic standards

The conclusion is that school plays a role in socialisation, but not as much as peers, family, your environment and societal attitudes. Education can’t compensate for 18 years of different life chances. As the sociologist John Goldthorpe says, class is often about “looking good and sounding right”; looking like you fit in, making the interviewer feel comfortable, picking up on social cues, saying the right things.

Schools are good for socialisation, in terms of how young people relate to each other, for making friends, helping adolescents find themselves and broadening minds. But they’re not incubators for the job market, and it’s a mistake to think of them as such. Eighty-five per cent of employers requiring a degree don’t specify the subject, they just want people to have had enough education.

And education is always a tempting lever for politicians to pull; it’s easier to change the education system than society more broadly. But while raising educational standards is a good thing that everybody wants, it doesn’t follow that it creates a more equal society. To have a more equal society you need to upgrade the economy – create better jobs. There’s an idea that investing in skills leads to better productivity and better jobs, but we’re not actually sure that it does.

We would do better to focus on schools making kids happier and healthier, with strong academic standards, rather than thinking they improve one’s position in the race for life. Grammar schools didn’t give more opportunities to more people, they gave more opportunities to the same people.

Peter Mandler is Professor of Modern Cultural History in the Faculty of History.