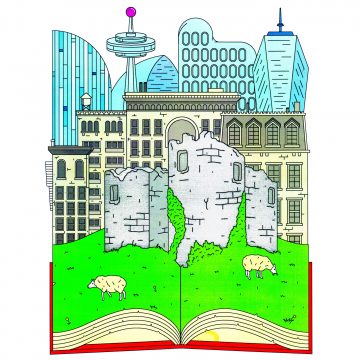

The “special relationship” between the US and the UK

The “special relationship” between the US and the UK has ebbed and flowed for more than 70 years. Can it adapt to survive for another 70?

The small city of Fulton, Missouri lies between Kansas City and St Louis in the American mid-west of America. With a population of just 13,000 people, its local attractions include an antiques barn, a smokehouse and a collection of historic motors – but also, and impressively, America’s National Churchill Museum.

For it was here, in March 1946, that British Prime Minister Winston Churchill stopped off with US President Harry Truman and delivered a speech that would embed not one but two, concepts in the global political consciousness: the “Iron Curtain” between the Soviet sphere and the West, and the “special relationship” between the United States and Great Britain.

In his 1946 speech, Churchill had warned: “Neither the sure prevention of war, nor the continuous rise of world organisation will be gained without … a special relationship between the British Commonwealth and Empire and the United States.” This would require “not only the growing friendship and mutual understanding between our two vast but kindred systems of society, but the continuance of the intimate relationship between our military advisers”.

The “friendship that saved the world” and arguably the origin of the special US/UK relationship.

Yet although Churchill’s words are clearly rooted in their immediate post-war moment – the defeat of Fascist Germany and Italy, and Imperial Japan, with former ally Russia turning inward – the website of the US embassy in London today makes frequent reference to this partnership proclaimed more than 60 years ago. “The United States has no closer ally than the United Kingdom,” it declares. “And British foreign policy emphasizes close coordination with the United States.”

So what exactly is the “special relationship”, both as a concept and a diplomatic reality? Did it really begin in 1946 and in what form has it survived to the present day? Perhaps most importantly – can it endure?

The special relationship is real. It’s not just a UK construct to bolster the image of a smaller country relative to a larger one

“The special relationship is real,” says Gary Gerstle, Paul Mellon Professor of American History. “It’s not just a UK construct to bolster the image of a smaller country relative to a larger one. The two nations share a conception that you could call ‘Anglo-American liberty’, which is important to people in both countries. It has been strengthened by alliances through the First and Second World Wars and the Cold War.” But it didn’t begin in 1946 – indeed, Nicholas Guyatt, Professor in North American History, says that, perhaps counterintuitively, a shared vision can be discerned throughout the American Revolution.

“Great Britain and the US had a fraught relationship after the American Revolution [of 1775-83] – and obviously the relationship before the Revolution was not so hot, either,” Guyatt says wryly. “However, in some ways, the Revolution was rooted in the failure of British officials to devise a political structure which could contain and recognise white American colonists’ claims to equality within the British Empire. We usually think of Empire as British officials ruling over non-Europeans, usually without their consent. But the US-British relationship was born in a different moment in which American colonists (ultimately the white Founders of the United States) were co-workers in the project of extending British influence, territory and power into indigenous territories in the American interior; and, of course, in the related project of producing commodities for sale back in Europe, often via the use of enslaved labour. So the American Revolution can sometimes stop us from seeing that white colonists and British officials were really engaged in a single project of colonialism before 1776.”

Guyatt’s latest book, The Hated Cage, delves into a case in point: the often-overlooked War of 1812 over British violations of US maritime rights and America’s desire to expand its territory – and the last time the two countries took up arms against each other. You’d expect the conflict to be a nadir of bilateral relations, but Guyatt suggests that instead it cleared the path to a new understanding of the two nations’ altered mutual standing. “The war’s messy and inconclusive course suggested to politicians on both sides of the Atlantic that the US and Britain might have more to gain from co-operation than conflict,” he says. “Paradoxically, while the War of 1812 seemed initially to demonstrate deep-set enmities between Britons and Americans, it actually facilitated a recognition of mutual interests, including an interest in bringing the non-European peoples of the rest of the world into an Anglo-American orbit of empire, commerce, Christianity and, on frequent occasions, violence.”

A formidable alliance in a time of increasing Cold War tensions and fears of communist expansionism.

Of course, the US would soon surpass the UK on the global stage. “In the late 19th century, as the United States formally annexed overseas territories, many people in the US began to recognise this expansion of their nation as an empire,” says cultural historian and associate professor Julia Guarneri. “This moment is when popular perception arises of the UK as in some ways a predecessor empire. A model to emulate as a world power, but also to surpass.”

The shift is captured in an 1898 letter written by Rudyard Kipling to his friend Theodore Roosevelt, then Governor of New York, enclosing his as-yet unpublished imperialist poem The White Man’s Burden. “Kipling sends Roosevelt this poem to try and persuade him that the US must govern the Philippines, because the Filipinos cannot govern themselves,” Guarneri says. “The poem says it will be difficult and thankless, but that it is America’s responsibility and the right thing to do. More broadly, Kipling is also asking Roosevelt and the US to follow in Britain’s path and emulate what Europe has done in colonising the rest of the world.”

America never replicated the British colonial model (although its insular Government of the Philippine Islands remained in place from 1901-35), and by the early 20th century, the Irish struggle for Home Rule had cast a chill on UK-US relations. That made the US decision to enter the First World War alongside Britain more complex than it might at first seem. “The US is made up of immigrants, and many at that time were Irish,” notes Guarneri. “They felt betrayed by this decision.”

The British created an enormous war machine that was hugely dependent on American supplies

It is notable, says assistant professor and foreign policy and intelligence historian Dan Larsen, that by the end of 1915, the British were cracking American diplomatic codes. This wasn’t a sign of hostility. “At this point in the war, British codebreakers started tackling neutral diplomatic codes, and the most important neutral in 1915 was the United States.” But the major effect of the war on the special relationship was to emphasise the tilting power balance first implied by Kipling’s desire to shift – or at least share – the ‘white man’s burden’ with America.

“In the middle of the First World War, Britain and America celebrated a century of peace from the conclusion of the War of 1812,” says Larsen. “On the British side, it was a complex experience. There was still that notion of kinship, but at the same time a suspicion of American profiteering, of America taking advantage at Britain’s expense. The British created an enormous war machine that was hugely dependent on American supplies, and there was a big debate within the British government between the view that the Allies could go it alone, and the contrasting recognition that there had been a shift in the transatlantic balance and that they could not win the war without American help. The start of the shift toward American hegemony is the biggest legacy from this period.”

In both of these moments, you have two powerful countries legitimising each other’s empire-building

But there are other echoes, too. The groundbreaking intelligence-sharing established during the Second World War is still with us today, Larsen notes. “Through human history, intelligence has generally been a lone-wolf operation, so to get countries co-operating so closely in intelligence – such as Britain and the US in the current Five Eyes pact with Australia, Canada and New Zealand – is striking.”

For Guarneri, Kipling urging Roosevelt to pursue American imperialism is mirrored in Prime Minister Tony Blair’s 2003 decision to send British troops to Iraq at the urging of President George W Bush. “The United Nations did not back Bush’s move, but the UK did. In both of these moments, you have two enormously powerful countries legitimising each other’s empire-building.”

A friendship forged through a series of legacy events, such as the peace process in Northern Ireland.

If the special relationship has survived domestic hostility, economic rivalry and outright war, can anything break it? Gerstle concedes that if neoliberalism has bound Britain and the US together for the past half-century, it’s possible that as that neoliberal consensus unravels across the developed democratic world, the special relationship could finally fray. “Neoliberalism speaks to an intersection of political thinking,” says Gerstle. “It was carried out in the US and UK under its two most important political creators, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. And when their respective opponents, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, came to power, they continued those principles. Neoliberalism went from two countries to the world.”

However, Brexit has unsettled many Americans, he says, seeming to diminish Britain’s utility as a gateway to Europe, and potentially threatening the Good Friday Agreement on the future of Northern Ireland. “That would be perceived with a lot of anger in the US, given the deep sympathy for the Irish experience, and its centrality to the American experience.”

Nonetheless, given the sheer length of mutual history, the two countries are likely always to find their way back to each other. “Reforming groups in both countries at different moments, such as in the 1830s and 40s with abolitionism, have made common cause to critique the current order,” says Gerstle. “Underlying that is an understanding that Britain and the United States share certain values regarding liberty, equality and the public interest. This has been a recurring pattern, so there’s every reason to believe it will happen again.”