After 750 years, is the mother of parliaments in need of reform?

A global pandemic. The potential break up of the Union. Extremism. Fake news. The UK faces numerous challenges, but is our democracy up to it? CAM asked four experts for their reforms.

The modern British parliament is one of the oldest continuous representative assemblies in the world. But after more than 750 years of service, is it time to give up on a system that majors in tradition but struggles with cooperation, devolution and extremism? Can parliament respond to the needs of modern democracy? We asked four Cambridge experts to set out their approach to reform.

Abolish Standing Order Number 14

Professor Alison Young, Sir David Williams Professor of Public Law at the University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of Robinson College

One of the biggest problems is that all the rules about how parliament regulates itself are determined by… parliament. Members can decide to change how parliament operates without any other kind of check. But one of these rules is particularly problematic.

Standing Order Number 14 states that the government’s business has precedence at every sitting. In practice, it allows the government to decide what you debate, when you debate it, and how long you debate it for – with just a few exceptions. This gives a huge amount of power to the executive and makes it very difficult for the opposition to hold them to account.

In times of crisis, of course, you need a strong and decisive government, unencumbered by too much restraint and process.

And that’s the argument in favour of Standing Order Number 14: think of the swift action of the Coronavirus Act 2020. But the downside is something like the EU (Withdrawal Agreement) Act 2020 – hugely constitutionally important and incredibly complicated – and pushed through with just three days of debate in the House of Commons.

Most other systems make these decisions using a cross party committee – assessing how important the legislation is, how problematic it might be, or how complex it is – while including a separate mechanism to trigger emergency legislation. This means you can take over the timetable if the issue is urgent, but you can’t if it’s not.

Standing Order Number 14 also has a more insidious effect: it forces parliament into being an arena, where MPs bring up issues to score political points and debate, while not effectively amending or scrutinising issues in detail, simply because they don’t have time. In fact, a lot of the scrutiny takes place away from debate in the house, in corridors rather than on the floor of the House.

There are two emerging voices within UK constitutionalism: Whitehall and Westminster. Westminster sees the sovereignty of parliament as the sovereignty of government: it prioritises effective government, strong leadership and the ability to get things done as more important than democracy and accountability. Whitehall believes we have parliamentary sovereignty because it promotes democracy and elements of democratic decision-making that will create better decision-making choices. I’m with the latter: democratic decision-making is more important, and I believe Standing Order Number 14 makes it far harder.

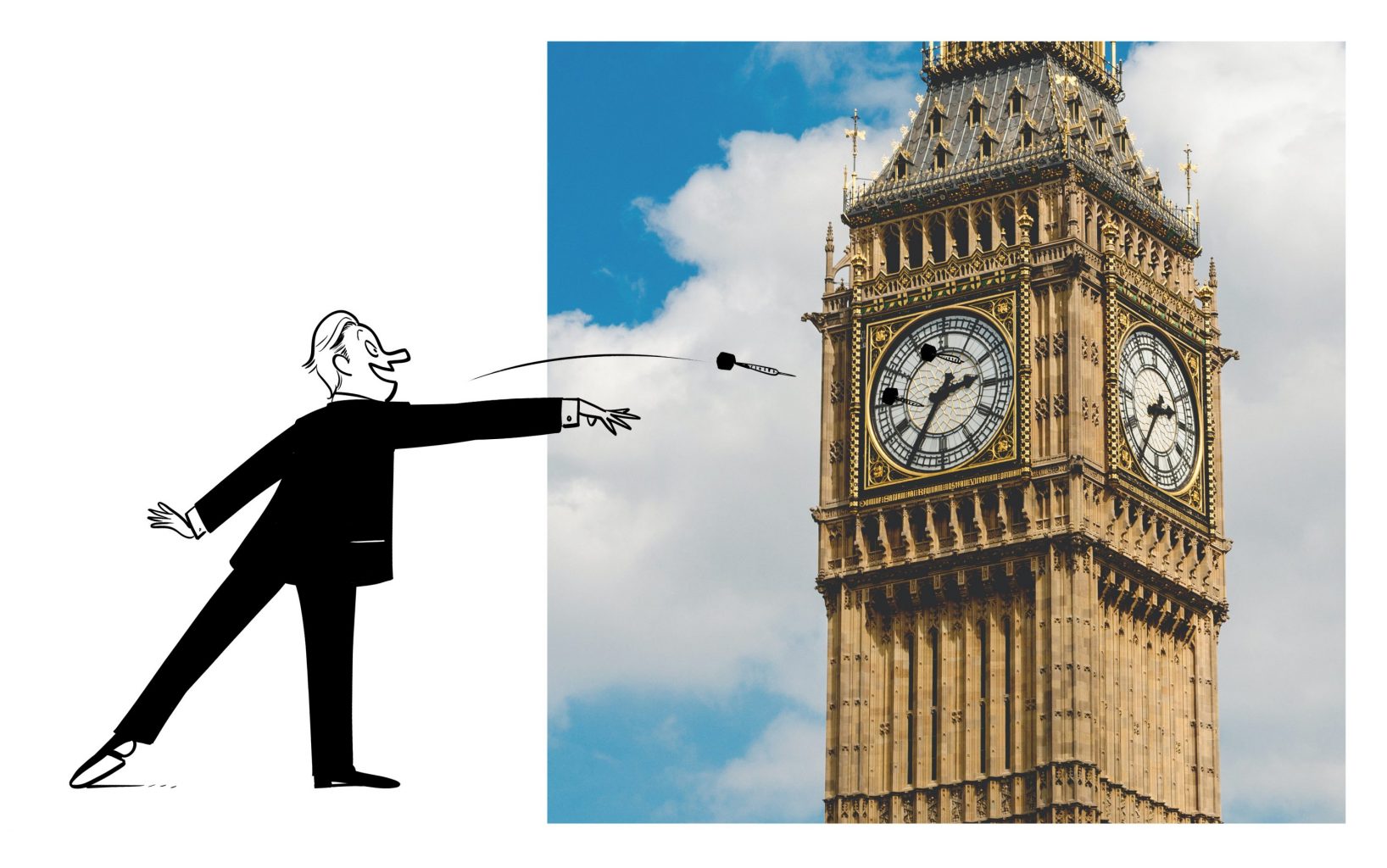

Design a new building

Professor David Feldman, Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of English Law and Emeritus Fellow of Downing College

Picturesque as the Palace of Westminster is, its design is an obstacle to what most countries would regard as sensible consensus-seeking in politics. So, my proposal is a new building.

One of the big challenges for politics generally – and party politics in particular – is how to overcome entrenched tribalism and develop a willingness to listen.

The current chamber design is only suitable for two-party politics, where the two parties want to shout at each other. It is not a good design for multi-party politics or consensus building. My building would have horseshoe chambers; committees already seat themselves in horseshoe formation. This would create a less confrontational space, allowing discussion.

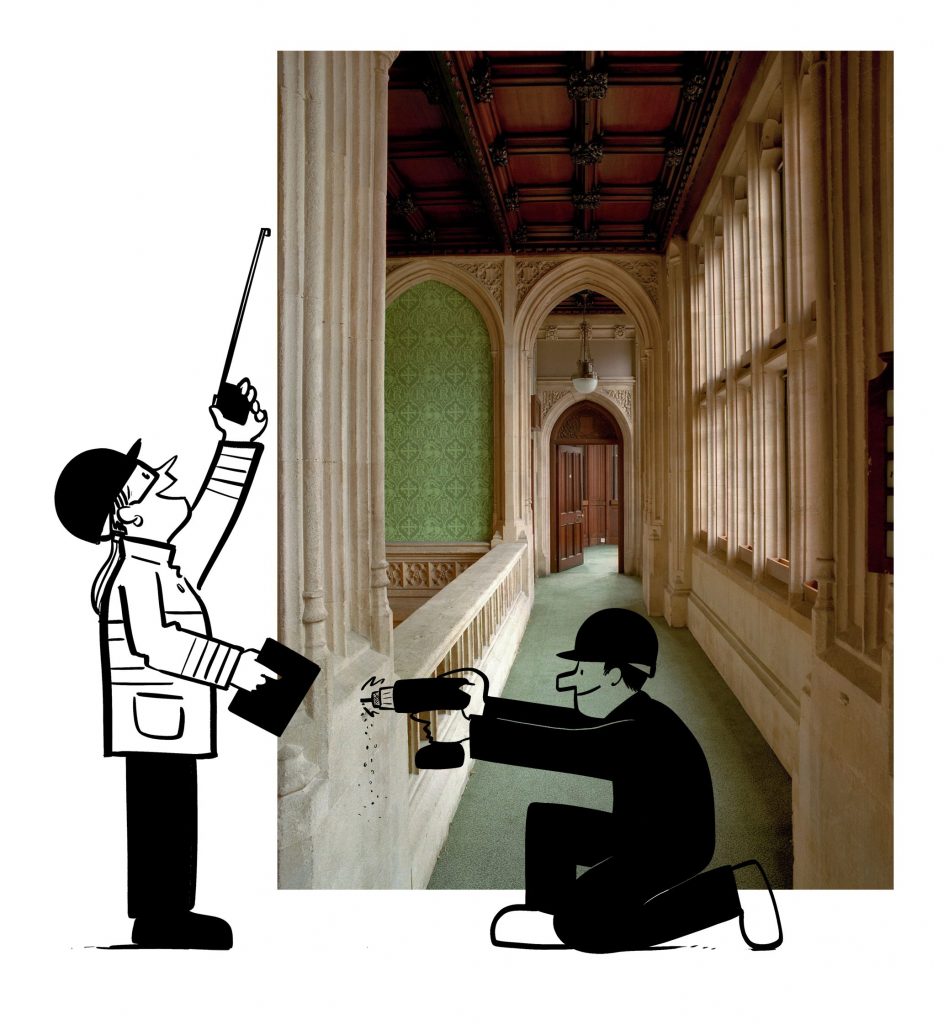

We also need a new breed of politician

Outside the chamber, MPs’ offices are of variable quality, with insufficient provision for staff, and are distributed by parties’ whips. Some members have no secure, indoor access to the chambers, and have to leave their offices, run downstairs and often across a busy road, risking life and limb in order to vote on a vitally important issue. This is one of many aspects of parliament that is unconducive to good government. Many MPs lack working space in the Palace of Westminster, because there is simply not enough room for them.

Ideally, all offices, for members of both houses, should be in the same building, and provide sufficient space for members to work efficiently with their staff.

Of course, a building alone will not improve the state of our politics, which, at the moment, is profoundly depressing. For that, we also need a new breed of politician. But should they arrive, we will need to give them facilities that will at least not discourage constructive discussion.

Change the electoral system used for the House of Commons

Professor Michael Kenny, Inaugural Director of the Bennett Institute for Public Policy and Fellow of Fitzwilliam College

The conventional arguments for proportional representation (PR) are that it would mean more people are likely to feel that their vote counts, it would encourage MPs to work harder to address a wider range of opinion in the areas they represent, and it may enable a much clearer and quicker expression of growing public concern than the current system allows for.

But there is a different argument for PR, and this is a retrospective one. Had we had a more proportional system for electing MPs, it is quite possible that some of the dynamics that have resulted in such deep political divisions between different parts of the UK might have been mitigated.

First, the Scottish Conservative party and, since 2007, its Labour counterpart would not have collapsed so dramatically in terms of their representation within Westminster. Both would have continued to elect a few MPs, and their party leaderships would have remained more engaged with Scotland as a result.

Equally, the SNP’s share of seats won would have been a bit smaller, which would have had a big impact on how the politics of Brexit would have played out at Westminster. And, had the Conservatives not lost so many MPs in different post-industrial areas across England since the mid-1990s, especially in the north, a very different kind of policy approach and programme might well have taken hold in the party after 2010.

The Tories might well have remained more connected to a broader range of opinion and interests across England. And, conversely, a Labour party that had kept more representation in the southern parts of England, and not been so dependent on representation in large metropolitan cities, might have thought differently about its own policies. As a result, the geographical differences in the two main parties’ representation in the Commons, which has been a notable feature of politics since the Millennium, might have been mitigated – to some extent at least.

There is now growing support for PR for a very different reason. In 2015, UKIP gained four million votes but won just one parliamentary seat – an outcome that left a significant body of political opinion unrepresented. It is interesting that this happened so close to the Brexit referendum of June 2016, no doubt compounding the feelings of many that their voices were not being heard in the political system, and that radical change was needed. It could be that support for PR will now grow across the left-right and pro- and anti-Brexit divides.

Shake up the second chamber

Professor Robert Tombs, Professor Emeritus of French History, Fellow of St John’s College

There’s a famous Cambridge maxim that says: never do anything for the first time. And that’s relevant when we talk about reforming the House of Lords, something that’s been debated for at least the past 100 years.

If a second chamber has a role, then it is surely in some way to represent the country against the establishment. During the Brexit debates, it became obvious that the House of Lords has become the opposite of that: it was completely out of line with majority opinion, even more so than the House of Commons. There is something deeply wrong there. It’s hard to see what justification anyone could come up with for doing it this way.

What might we replace it with? You can’t just start again and design a perfect second chamber. At the moment, the House of Lords is too big, too old and too narrow. It’s an agreeable drop-in centre for retired politicians and civil servants, but we should limit tenure for those sitting as legislators and separate the honours system from the legislative function.

Perhaps we should redesign the chamber to attract younger people who want to change things but who don’t want to take over the House of Commons’ powers. A bit like the American Senate, we would need a younger and more active house with clear responsibilities, including in foreign policy and in vetting appointments. Many people would like a house that represents the regions and the nations of the UK, or some of its major institutions. It would have to be kept out of the hands of the established parties, so we would need to find a way of preventing constant deadlock with the House of Commons – which, of course, you often get in the USA.

I’m tempted to just abolish it altogether

Perhaps this is impossible and, instead, we should simply ask: what is the purpose of having a second chamber at all? It doesn’t represent the country against the establishment: it’s the citadel of the establishment – or, at least, the previous generation of the establishment. If it wasn’t there, what would we actually miss? What do the Lords do that could not be done by the courts, or some sort of judicial body? So, I’m tempted to just abolish it altogether.