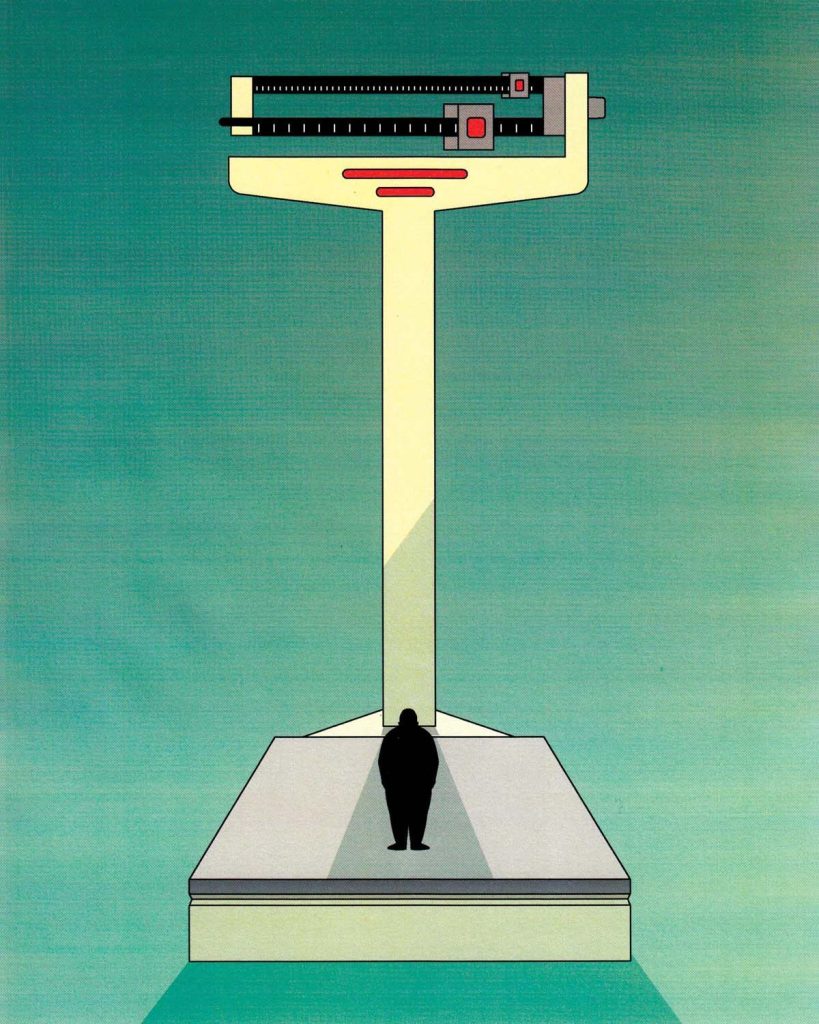

This idea must die: “Obesity is caused by lack of willpower”

Professor Sadaf Farooqi says being slim is a matter of luck, not a demonstration of moral superiority.

The myth that obesity is simply down to a lack of moral fibre or willpower is simply not true – but it is incredibly pervasive. Highly educated people still believe that you can control what you eat; that people with bigger appetites are simply greedy. But we have known that this is not the case for a very long time.

In 1994, Professor Jeffrey Friedman discovered a hormone called leptin, which regulates our appetite via pathways in the brain. This paved the way for unravelling the system that regulates our appetite and weight. It was followed by our own work at the Wellcome-MRC Institute of Metabolic Science in 1997, where we showed that people who lacked leptin developed severe obesity. They also had an incredibly strong appetite and desire to eat.

The discovery of leptin and how it works showed us that there is a system that regulates our appetite and our weight. In most people, that system works pretty well and keeps weight stable. But that system can be altered or damaged – by a tumour, for example, or by certain drugs, or by a genetic condition.

That explains why some people have larger appetites and gain weight more easily, why other people have smaller appetites, and why some people can eat what they like and they never gain weight. That variation is strongly influenced by our genes, and those genes, in turn, act on pathways in the brain.

When I did my PhD at Trinity 25 years ago, we identified the gene that makes leptin. And then we explored the fact that the children who were lacking that gene and, consequently, leptin, had an incredibly strong desire to eat and had gained a lot of weight. We ran the first clinical trial giving these children injections of leptin, the missing hormone. It dramatically normalised their appetite. They would then turn away food and eat normal amounts, and they lost a dramatic amount of weight. We proved that leptin as a hormone is a critical regulator of appetite. Subsequently, we and others have found several different genes that are part of this system that regulates appetite and weight. If any of those genes are faulty, then people are more likely to gain weight.

One of the most important outcomes of our research has been to challenge the idea that this is all someone’s fault – because we can prove that it’s not. We can prove that there is biology at play here

We can now test for those faulty genes, and this can be a big help because obese people are often blamed by their doctors, and others, for being heavy. One of the most important outcomes of our research has been to challenge the idea that this is all someone’s fault – because we can prove that it’s not. We can prove that there is biology at play here.

As a doctor, it is never helpful to blame people for something that is difficult to control or difficult to manage, telling them it is entirely in their hands to sort it out. That often damages the relationship and makes people much less likely to seek help. And when people are stigmatised or discriminated against because of their weight, it has a massive impact on their lives. We see the impact on children from a very young age. There is very good evidence that what we call weight stigma impacts on people’s educational performance, on their interactions with healthcare professionals, and on their life opportunities.

In fact, the discourse around obese people reminds me of how, centuries ago, people used to think that people with epilepsy were possessed by spirits. There were so many areas of medicine we didn’t understand. And because we didn’t understand them, we would blame something else. It has been very easy to blame people and, interestingly, often the blame comes from people who have never struggled with their weight. But our work has shown, by studying a cohort of thin people, that thin people are thin because they have fewer genes that increase their chance of obesity, and additional genes that are keeping them thin. So, if you are thin, remember: you are not morally superior – just lucky.

Professor Sadaf Farooqi is the Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellow and Professor of Metabolism and Medicine.