Metalheads

A lecturer in Criticism at the Faculty of English, Dr Ross Wilson says that heavy metal and critical theory have more in common than you might think.

The Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert at Wembley Stadium aired on BBC2 on Easter Monday in 1992. I was 13 years old. By that stage, I’d listened to a lot of Queen, mostly cassettes in my dad’s car, and I was looking forward to the concert because a couple of bands I liked – Def Leppard, Guns N’ Roses – were playing.

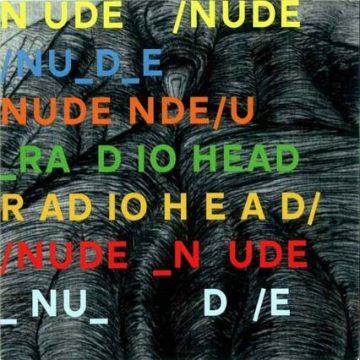

But what really piqued my interest was a band I’d heard a lot about from reading the hard rock/heavy metal press, but who, in spring 1992, I hadn’t actually heard yet: Metallica. I already somehow intuited that Metallica weren’t really much influenced by Queen or even that similar to the other bands I liked: Guns N’ Roses, Def Leppard, Bon Jovi, Skid Row and Aerosmith. Metallica were first up at Wembley and from the moment they stormed the stage on my dad’s portable TV, I was awed. My journey from rock to metal – and an appreciation of the distinctions between thrash, speed, death, stoner, groove, doom, progressive, extreme and traditional varieties of metal – had begun.

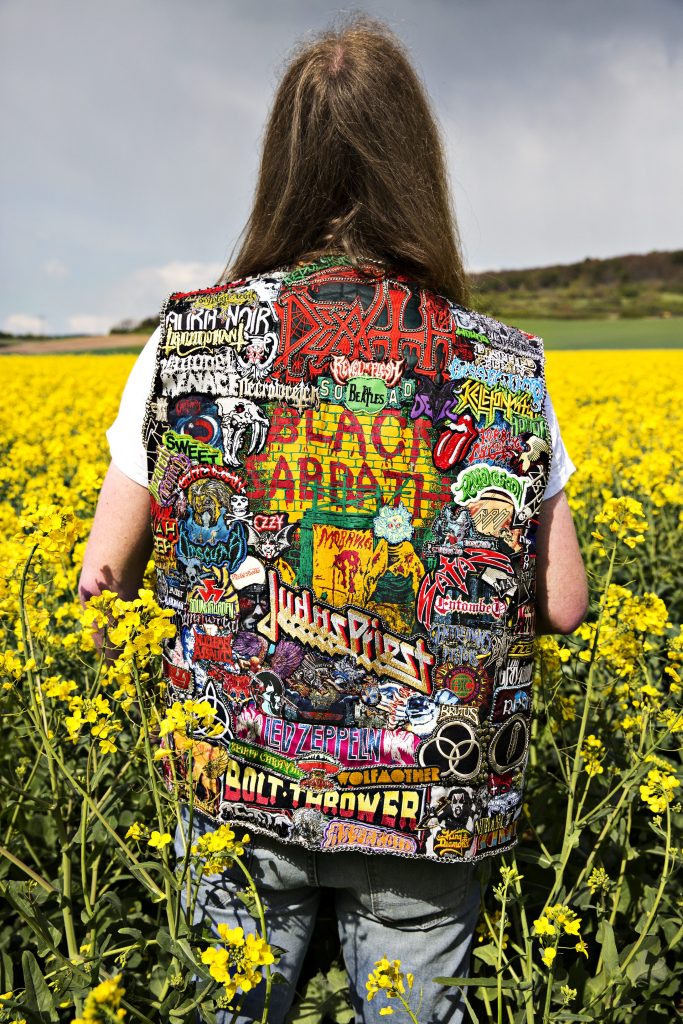

I was 13 then. I became a dedicated and unapologetic metalhead for about four or five years, but even afterwards the affinity remained. My metallic credentials weren’t always outwardly displayed: while I had lots of black T-shirts with skulls on them and tight black jeans, I could never do the hair (too curly, too upward). I’m nearly 40 now: a husband, father, Fellow of Trinity and a lecturer in Criticism at the English Faculty. But I find myself drawn back to metal, both as music to listen to and (in a strange way, I admit) enjoy, and as a way to ask questions about criticism, critical judgement and how taste is formed.

Kant’s idea that you ought to be able to share your judgements of taste with everyone else runs up against my indelible love of loud, obnoxious music.

Reflection on the formation of taste has produced some really significant insights both into how artworks get produced and how they come to be the focus of criticism. The narrator of Marcel Proust’s A La Recherche du Temps Perdu has pride of place, perhaps, among those who have charted both their development as artists and the gradual honing of their critical faculties. More recent examples include: Elif Batuman’s candid memoir (The Possessed) and mordantly witty novelisation (The Idiot), which record her emergence as a devotee of Russian literature (hint: she quite likes Dostoyevsky); Francis Spufford’s touching and exuberant recovery of childhood reading (The Child that Books Built); and Frank Kermode’s revealing account of the gradual shaping of the identity of the critic (Not Entitled).

A question of taste

But my first authentically personal set of aesthetic experiences and preferences – the experiences that put me on the road to thinking about what it is to have a taste of one’s own for something, to be critical (in the positive sense) of it – were of heavy metal. Recognising this fact has forced me to revisit some major tenets of aesthetics in ascendance since the Romantic era – and to which I thought I adhered, but that, in fact, sit rather awkwardly with my basic experiences of the formation of taste.

In my peak heavy metal years, I agonised over what real and uncontrollable effects listening to the nastier end of metal might have on me.

For instance, the idea that, while subjective, you ought nevertheless to be able to share your judgements of taste with everyone else – which is the crucial insight of Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Judgement, the founding text of modern philosophical aesthetics – runs up against my indelible love of loud, obnoxious music. My love of heavy metal wasn’t – isn’t – easily shareable and it isn’t something I expect others to share. To be sure, I quite liked it when my dad thought the opening of Megadeth’s ‘Holy Wars’ was good, it was great when my mum really liked Metallica’s ‘Sad But True’, and I think my wife is wrong not to be able to differentiate between Carcass and Morbid Angel. But, on the other hand, there is something totally singular about my love of this kind of music that means I know I can’t quite share it and I don’t always really want to.

There is an important moment in Critique of Judgement where, in the course of his ground-breaking meditation on the nature of judgements of taste, the philosopher imagines a ‘youthful poet’ who won’t be shifted from the good opinion he holds of his own, perhaps rather indifferent, juvenile poetry.

Kant comments: “It is only later, when his judgement has been sharpened by exercise, that of his own free will and accord the youthful poet deserts his former judgements.” What Kant is getting at is the idea that we should allow our own critical faculties to develop through exercising judgement, honing it on different materials.

But there’s probably something all of us – and not just poets, literary critics, or even lecturers in criticism – can recognise in the figure of the youthful poet, in the young person starting to develop her or his own taste, starting to practise judging different kinds of artworks, and coming eventually to abandon things that they have cherished – or perhaps, actually maintaining a secret devotion to the tastes and preferences of their untutored youth. On the one hand, Kant wants to maintain a role in his new aesthetics for older views of taste that put considerable emphasis on the authority of ancient, commonly accepted models; on the other hand, he never quite comes out and says that the youthful poet is bound to reject his early attempts at poetry. Perhaps, he sticks to his view that those poems are good; perhaps the self-appointed arbiters of taste are wrong; or perhaps, no matter how much practice at forming critical judgements he has, he just can’t shift his initial devotion to his early works. Perhaps, then, my devotion to heavy metal is not going to budge, no matter how hard I try to shift it with years of cultivation and critical reflection.

Metal and ethics

So, heavy metal troubles in various ways the idea that judgements of taste are subjective but shareable. In contrast, perhaps, it also explodes the alleged post-Romantic indifference to genre. Where Romanticism is often held to have inaugurated an epoch of freer artistic creation, dispensing with observance of established conventions of specific genres as a condition of artistic excellence, heavy metal is amazingly generically differentiated: there’s thrash, speed, death, stoner, sludge, groove, nu (or is that nü?), doom, progressive, extreme, traditional – and that’s just for starters. And, of course, the elemental difference between heavy metal and hard rock is crucial to the whole enterprise.

Another principle I’ve adhered to for a long time – but have come to rethink as I rediscover the roots of my own interest in questions of judgement, taste and criticism – is that the ethical, political or religious content of a work of art is distinctly secondary to its status as a work of art. Indeed, in my peak heavy metal years, I agonised over what real and uncontrollable effects listening to the nastier end of metal might have on me.

I was anxious about listening to Slayer’s Hell Awaits on a Sunday (I wasn’t comforted by my mother’s anti-sabbatarian remark that it didn’t matter what day you listened to it).

And I once put the loss of my tram ticket, apprehension by the ticket inspector and £10 fine (a painfully large sum to a teenager in the early 90s) down to the fact that on that particular trip into Manchester I’d bought a cassette of Obituary’s surely satanic album World Demise.

It wasn’t that I thought I was going to become a wicked person and go on a murderous rampage as a consequence of listening to this music (although, again, neither do I think that being worried about the fact that this does appear to happen to some people should be dismissed). It was rather that I imagined that listening to Slayer, Obituary, anything at the death-y, Satan-y end of the spectrum, was in itself wrong and was going to bring down on me the workings of some form of divine judgement.

Connected to this unease is the fact that I did most of my heavy metal listening in my mother’s flat in a nice suburb with a large Jewish population in north Manchester. And so it made my mother particularly uneasy that I wanted to wear T-shirts with drawings of skulls and piles of bodies on them. She was right to be uneasy, and I think that my sense of the complexities involved in the artistic depiction of cruelty and carnage – a problem that has exercised both classical and modern thinkers – has its roots not in Aristotle or Edmund Burke or Kant, but in heavy metal.

The American writer Maggie Nelson has written that “the spectre […] of our (live) flesh one day turning into (dead) meat […] is a shadow that accompanies us throughout our lives”. It is a shadow that is cast on a grand scale by the pyrotechnic glow of heavy metal, whose whole aesthetic resonates with Nelson’s at once ghostly and fleshy description. So, one question any serious criticism of heavy metal must confront is whether its awareness of the fate of ‘our’ flesh turns too often into a macabre glee at the – again, real and imagined – fate of the flesh of others.

All critics must attempt to think through the emergence and development of their own critical preoccupations, but somewhat disturbingly, even a cursory examination of my love of metal seems to overturn a number of critical tenets I’ve long held central to my own research and thinking.

Perhaps more reassuring is the fact that it was in relation to heavy metal lyrics that I first practised what I can now recognise as ‘close reading’ – that mainstay of ‘Cambridge English’. To be sure, devotees of other musical forms could say the same thing about, for example, rap or folk and their subgenres. But it isn’t just because heavy metal bands have a habit of invoking Coleridge and Tennyson (as Iron Maiden have done) or, indeed, of setting Schopenhauer and Schelling to music (as the fittingly named Obscura do) that I think they’re especially conducive to the formation of philosophically inclined literary critics.

It was in heavy metal that I first encountered many, to my youthful eye, unheralded words – words like ‘avidity’, ‘mandatory’, ‘foreclosure’, as well as a whole range of doubtless misused military, theological and medical terminology. This was not least the case in the music of the British heavy metal band Carcass (surely, by the way, the best band ever to have come from Liverpool), whose lead singer wrote lyrics by means of obsessive recourse to the medical dictionary he borrowed from his sister who was training to be a nurse.

Still, it’s probably a good thing that someone who spent his teenage years listening to songs like Corporal Jigsore Quandary and Ruptured in Purulence was inspired to become a literary critic rather than, let’s say, a doctor.

Dr Ross Wilson is a Fellow of Trinity and an unashamed metalhead.

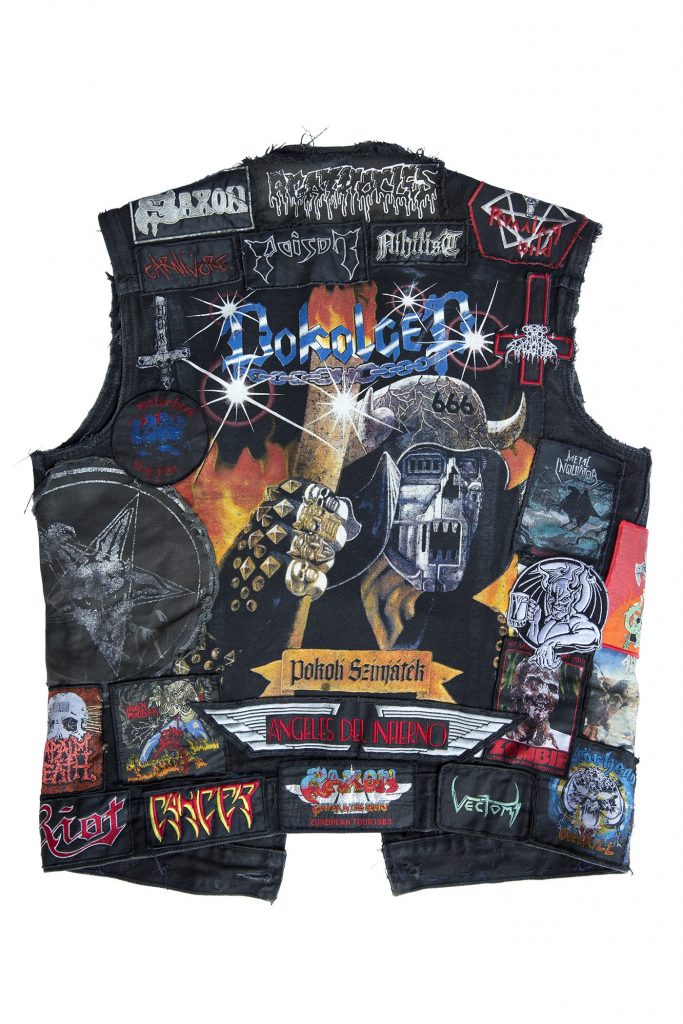

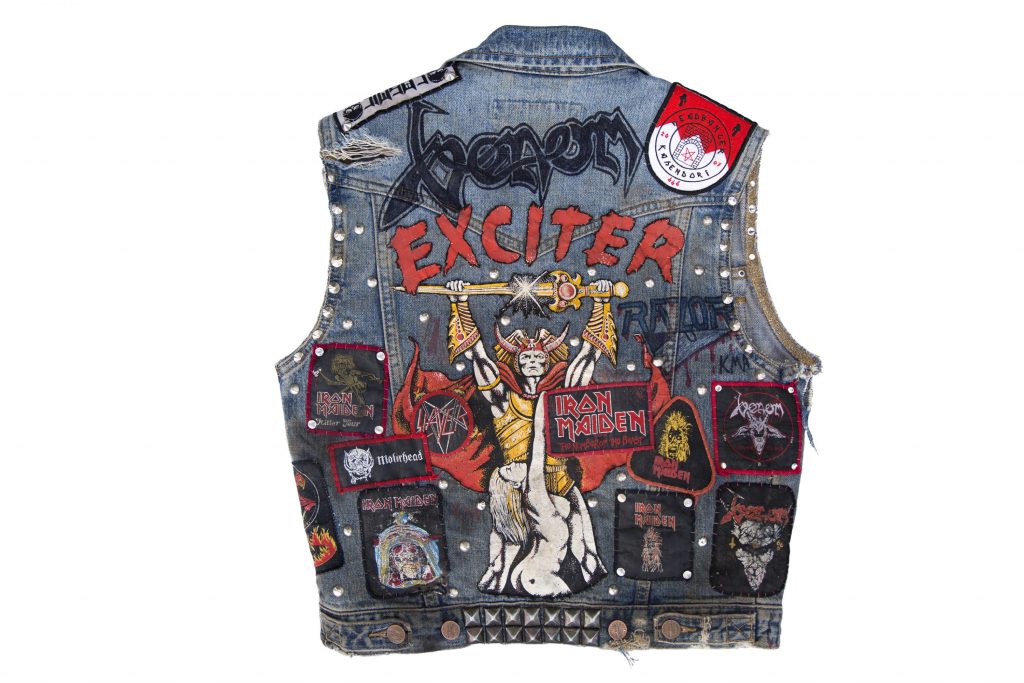

Oregon-based photographer Peter Beste says that his work seeks to portray subculture communities as they express themselves, without reference to outside opinions or ideologies. His book, Defenders of the Faith, from which these images are taken, is to be published later this year.