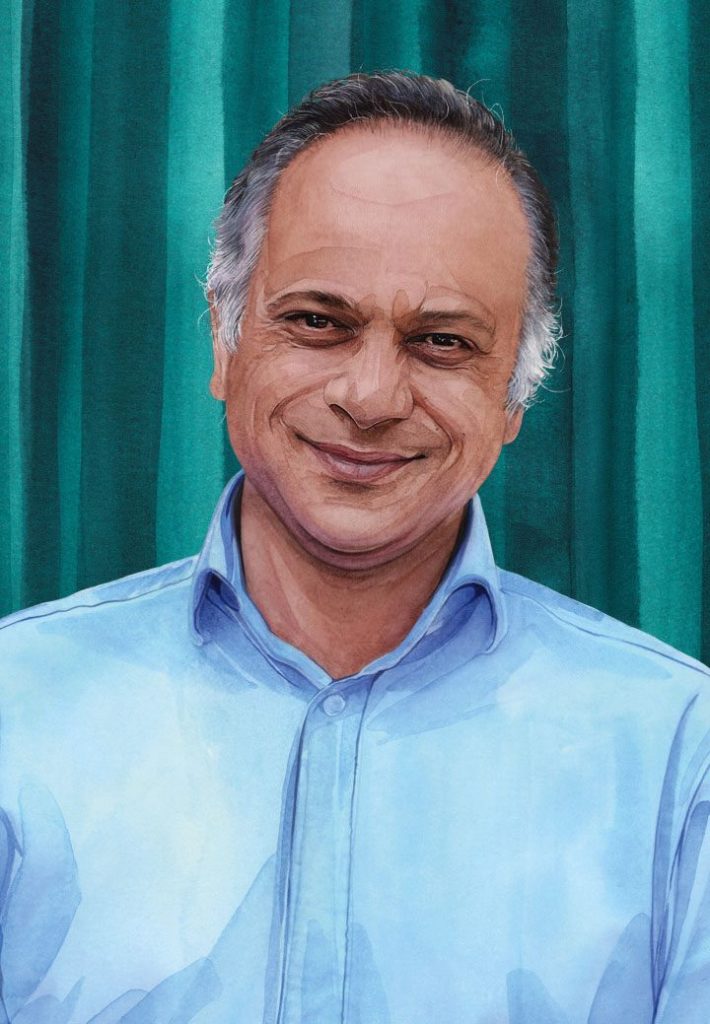

For true equality in postgrad education, we need a new vision

of Fitzwilliam College.

Postgraduate education is vital to our world. It allows students opportunities for advanced learning and to acquire the skills to conduct and perform research at the highest level, not just in academia but across all sectors, from tech to thinktanks. More than 80 per cent of our postgraduate students will not continue in a permanent academic role: they take their expertise to the wider workplace. But when postgraduate education becomes the preserve of a social or financial elite, the result is a narrowing of thought. That’s why we are taking action to create further opportunities for postgraduates to come to Cambridge, both from the UK and abroad.

In the UK today, there are huge barriers to postgraduate education, particularly for those from underrepresented backgrounds. While the ownership of an undergraduate qualification is widely associated with better employability and life chances, the benefits of postgraduate education are not as widely understood. So first-generation university attendees might believe that stopping at undergraduate level is enough. Where there is no social and family experience of any higher education, a postgraduate degree can seem completely out of reach.

Cost, of course, is considerable, for both UK and international postgraduates. Each year, postgraduate applicants gain places but cannot take them up. A study conducted among applicants showed that being unable to afford the place was the main reason that students did not come to Cambridge. We will never know what groundbreaking discoveries they might have made if they had.

Get In Cambridge, a programme for UK students, is making a difference: aimed at both undergraduate and postgraduate students from historically underrepresented ethnic minority communities at Cambridge, it now funds a significant proportion of Master’s students.

When postgraduate education becomes the preserve of a social or financial elite, the result is a narrowing of thought

But if we truly want to widen participation for postgraduates, providing funding is only the first step. We must ensure that those who haven’t historically aspired to a Cambridge education feel that it is attainable. That is why several schools, faculties and departments now run summer programmes to give prospective postgraduates from non-research-active universities experience of working in a lab or a research group, such as Experience Postgrad Life Sciences at the School of Biological Sciences, and the SHARE Summer Research Experience at the School of Humanities and Social Sciences. It’s about raising aspiration for people who have not, historically, had the opportunity to consider a research career.

We have just launched the Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program, supporting African students on postgraduate degrees at Cambridge linked to a broader programme around climate resilience and sustainability in Africa. This scheme has only been running for a few months, but we can already see that the numbers of applications from African students for Master’s programmes have increased significantly.

We are also reaching out to organisations overseas, such as the Posse Foundation in the US, which works with socially and educationally disadvantaged groups. We don’t have the capacity to understand disadvantage in other local contexts, given that we recruit students from more than 100 countries. I want to find and work with similar organisations globally who can help us find those students who are most deserving of support, through their deep understanding of social and educational disadvantage in their national and regional contexts.

Master’s and PhD students are often at the cutting edge of research, coming up with innovative new ideas. And for that, we need a robust research framework set by diversity. That matters just as much in STEM subjects as it does in social sciences and the arts. To solve the right problems, you must first ask the right questions – and have the diversity of thought which enables that.

Find out more about postgraduate education and how you can support postgrads.