CAM presents: Emergency Education on Ireland

British ignorance of Irish history and politics is legendary (it’s a topic of academic study and Taoiseach Leo Varadkar even commented on it in public). Indeed, phrases such as the ‘Irish’ question and ‘Irish’ borders bizarrely leave out any suggestion of British involvement. So, to mark the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement, CAM delivers a piece of emergency education, asking leading Cambridge experts to give us their views on the issues that matter.

The Good Friday/Belfast Agreement was not just about peace

Dr Niamh Gallagher, Lecturer in Modern British and Irish history

Most people in Britain think the Good Friday Agreement just ended a sectarian conflict called the ‘Troubles’. This is based on the reductive idea of an ancient conflict between two ‘tribes’, but takes no account of the various structural factors, inequalities and domestic and international contexts that actually did give rise to something that became conflict in the 1970s and 1980s, or the very real problems that were solved by the Agreement.

Northern Ireland was created by Westminster in 1920 as a majoritarian regime answerable to the Unionist population alone. Though safeguards to protect the rights of minorities were included in the 1920 Government of Ireland Act, they were extinguished by the ruling Unionist party, which remained in power for 50 years. There was gross discrimination against minorities – of which Catholics were the largest – in everything from voting rights and housing allocation to employment.

This was the backdrop to the civil rights protests of the 1960s, when both liberal Protestants and Catholics lobbied for ‘one man, one vote’ and ‘British rights for British citizens’. They were infamously attacked by Ulster loyalists and members of the northern police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Then came the huge policy failures of both the Stormont and Westminster governments: the introduction of internment, the arrival of the British army with no clear remit of action, and horrors like the Ballymurphy and Bloody Sunday killings. Gross policy failures changed the nature of the conflict in the early 1970s, providing new dynamics that reinvigorated northern republicans who formed the Provisional IRA. Defeating the IRA soon became the British mantra. The ‘two tribes’ idea explains very little about how those early years of civil disturbance turned into something far more complicated and violent.

Jump ahead to 1998 and even the ‘solution’ to the ‘Troubles’ is more complicated than a peace accord. The Good Friday Agreement is an international agreement of which the multi-party agreement in Northern Ireland is just one part. It is a radical reinterpretation of political relations across these islands. For a long time, Unionists had feared the intentions of the Republic of Ireland. Articles two and three in its 1937 constitution laid claim to Northern Ireland. The Agreement arranged for two referendums, one of which was held in the Republic to remove these articles (94 per cent of people voted to remove them). In the north, the Agreement recognised the legitimacy of both minority and majority constitutional aspirations. It was deemed fine to want to stay within the UK and equally fine to favour a united Ireland. It abolished majoritarian government and introduced power-sharing. The Agreement inaugurated changes to policing, justice and human rights, all of which were qualitatively new additions to previous ‘solutions’ for solving the conflict.

Why violence hasn’t entirely disappeared is a more complicated question related to historical peculiarities, class, poverty, political failure, crime, drugs and, at some level, ideology. But in 1998, ‘peace’ was able to come about because real structural problems were solved. The two ‘tribes’ idea explains little about what was achieved.

There is no such thing as the ‘Irish Question’

Richard Bourke, Professor of the History of Political Thought

There is this thing called the ‘Irish question’ that episodically impinges on British politics. But that is a misformulation, because there is no ‘Irish question’ as such. There’s an English question, because England is the largest player in these islands. It’s the most populous, latterly the most economically powerful, and the earliest centralised power in these islands. So the English question concerns how it will manage its adjacent territories: by separation, or – as it has periodically decided – by union, in various ways.

Prior to 1801, there was a federal union with a colonial parliament: an Irish Protestant parliament. Catholics were not properly incorporated into these jurisdictions and were not trusted: they were hostile to a Protestant crown. In the aftermath of the French Revolution and because of a rebellion in Ireland, Britain changed its policy, as Ireland having its own subordinated parliament looked like a security threat to Britain. An incorporating union was brought about in 1801 – as a solution to the English question.

Then, as a result of various forms of Irish discontent through the 19th century, there was a series of policy responses by the Westminster Parliament. Some favoured ameliorative measures with continuing union and some, principally the leader of the then Liberal Party, Gladstone, began to favour home rule. The solution was to create an Irish Parliament again, which was to be separate yet with federal links to the British Imperial Parliament.

That was intensely debated – and divided opinion in Britain and Ireland, leading to a threat of civil war in Ireland and arguably a threat of certainly very serious civil disruption in Britain as well, including in England. The solution arrived at in the early 1920s involved a strong measure of independence for Southern Ireland along with the partition of the island, forming the Irish Free State, later becoming the Irish Republic, together with Northern Ireland. Following a civil war within Ireland over the terms of that settlement, this arrangement lasted until the 1968- 1972 period, when it faced the possibility of collapse.

So the Irish question – which, we now see, is a product of prior British and English questions – came back on the agenda in 1968, but was settled once more with the Belfast/Good Friday agreement of 1998. Yet ‘the question’ then reasserted itself once more with the culmination of the Brexit debate: Britain, dominated by England in this regard, sought to reconfigure its relationship to the EU, promoting the need for a new relationship with the Republic of Ireland and, as soon became clear, with Northern Ireland as well. The Irish question appears once more as a product of debate about how Britain should manage its own domestic sovereignty and redesign its international political and trading relations.

I therefore get tired of the ‘Irish question’ – basically because there is no independent Irish question. If there were, it would mean that Ireland was driving the discussion each time, as though there had been a series of virtual Irish referenda since the 16th century posing all these different questions. Quite the contrary: the Irish question is the product of British statecraft.

The Great Famine was about finance – not just food

Dr Charles Read, British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Faculty of History and Affiliated Lecturer at the Faculty of Economics

On 16 August 1845, The Gardeners’ Chronicle and Horticultural Gazette reported “a blight of unusual character” on the Isle of Wight. A few weeks later, that blight had appeared across Europe – and, most disastrously, it had spread to Ireland. This was the beginning of the Great Irish Famine, which killed and displaced millions.

The 1840s were a decade of shortages – French grain harvests also failed in 1846-47. These shortages caused inflation not just in Ireland but across Western Europe. This was, of course, a problem for the British government. It had to work out how to redistribute resources to make sure the vulnerable could afford higher prices in the short term – and do so in a way which didn’t cause financial or fiscal instability. In March 1847, the British government announced plans to raise a £14m loan to pay for Irish famine relief.

But what caused the U-turn later that year that meant that central government spending on the famine was cut to virtually nothing rather than expanded to £14m a year? Historians have posited that it was anti-Irish racism, or laissez-faire ideology – the idea that the market would provide. But the real cause was far more straightforward. The 1847 budget contained both unfunded tax cuts and an expansion in the relief effort funded by borrowing, rather than tax rises. Consequently, interest rates surged and financial markets panicked, causing many banks and businesses to go under. Corn brokers who lent on trade in corn overleveraged themselves and came crashing down. The result? Central government slashed spending on Irish famine relief to almost nothing, to try and calm the markets – and the majority of famine mortality in Ireland occurred after this change in 1847.

Those mistakes made in 1847 reoccurred in the autumn of 2022, with Liz Truss’s disastrous mini-budget. In autumn 2022, the macroeconomic backdrop was similar: a shortage of energy because of the Ukraine-Russia war, leading in turn to food shortages. Inflation rose: at the time of writing, it is over 10 per cent in the UK. The announcement of unfunded tax cuts, plus a large amount of borrowing to pay for energy imports from the rest of the world, also triggered a financial panic. A U-turn and an austerity autumn statement followed, and the consequence, again, was higher winter mortality rates.

So the real lesson of the Irish famine should be that when a country is suffering scarcity and inflation – just like today – a government must redistribute resources to help the poor. But you must do it in a way which is fiscally sustainable and isn’t going to imperil financial stability. The damage caused in 2022 was entirely preventable, predictable and avoidable if that lesson had been learned – and acted upon.

The Windsor Framework will reduce the impact of the border – but it won’t rub it out

Catherine Barnard, Professor of European and Employment Law

I did dozens of town hall forums and public engagements in the run-up to the Brexit referendum, and I can recall only one instance where I was asked about the potential of Brexit for Northern Ireland. And that was from someone with a Northern Irish accent. There was a remarkable lack of interest or curiosity.

We were promised that Brexit would keep all the benefits of EU membership but without any of the obligations. And this was always untrue – because the Brexiteers hadn’t sorted out what sort of Brexit they wanted and most of them had little idea about the legal significance of leaving the single market and the customs union.

So what was that significance? The ‘Brexit Trilemma’ holds that you can have only two of the following three things: no hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland; no customs border in the Irish Sea; and the UK leaving the European single market and customs union. Boris Johnson committed the UK to leaving the single market and the customs union. So that meant there had to be a border somewhere. The logical place would be between the north of Ireland and the south. But that was effectively ruled out by the Good Friday Agreement. So there had to be an east to west border – down the Irish Sea. Johnson got round the Brexit trilemma by refusing to accept that there would need to be a border down the Irish Sea.

But the impact assessment that accompanied the text of the Withdrawal Agreement – where the Northern Ireland Protocol is located – makes it abundantly clear there would be an east-west border and there would be costs associated. That border particularly affects goods going from GB to NI, but it also affects some goods going from NI to GB.

The Windsor Framework aims to reduce the impact of that border. It hasn’t rubbed it out entirely and from that point of view, Rishi Sunak did oversell what he’d achieved. There will be checks, particularly on agrifood products, but they will be reduced. And the Windsor Framework will introduce a green lane for goods going into Northern Ireland: if goods are staying in Northern Ireland, then the paperwork will be significantly reduced.

Are relationships between the UK and the EU thawing? I don’t think we should get carried away. But I think there’s a certain amount of Brexit fatigue and desire on all sides to move forward.

The country in Western Europe which has changed more in the past 40 years than any other? Ireland

Daniel Mulhall, Parnell Fellow and former Irish Ambassador to the US

While it’s understandable that the British people know less about Ireland than maybe they ought to, our shared responsibilities in Northern Ireland will always require the two countries to know each other better than they perhaps otherwise would. And everyone in Britain ought to know that Ireland has probably changed more in the past 40 years than any other country in Western Europe.

First, economically: when Ireland joined the European Union in 1973, it was way behind the rest of the EU countries in its level of economic development. Now, it has caught up with those countries that were once significantly more advanced than Ireland. Alongside the impact of EU membership, this has transformed the way Ireland sees itself and its relationship with Britain.

And there’s been a kind of social revolution. Things that were deeply divisive up to the late 20th century – contraception, divorce, abortion – are no longer controversial. That same revolution has hit politics, too. When I was growing up in the Ireland of the 1960s, there were two big parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. It was always either one of those parties in government on its own, or the other party in coalition with the Labour Party and maybe some other smaller parties.

Today, those two historically dominant parties are in government together – it was the only way they could put together a majority capable of forming a government. In the last election, they got less than 50 per cent of the total vote. We now have eight or nine parties, plus a lot of people with independent political positions. The next election is not for another two years, but at this stage, the prospect of Sinn Fein being the dominant political party in Ireland is very real. In Ireland’s electoral politics, Sinn Féin is seen primarily as a left-wing party. Then there are changing attitudes towards Britain and Northern Ireland. When I was growing up, there was a sentimental attachment to Irish unity, which was strong but not very well thought out. Now people are much more aware of the challenges involved in that venture and, mostly, they are inclined to see unity as a longer-term proposition.

I take a moderate nationalist position in that I see a certain geographical logic in a future scenario for Irish unity. But it will take time for the necessary debate to mature. Much preparatory work would be required to make it viable and difficult issues will need to be teased out. More immediately, I hope that we will see a return of devolved government in Northern Ireland and the evolution of more normal relations between the EU and the UK, and between Ireland and the UK, now that agreement on the Windsor Framework may finally have put to bed those interminable wrangles over Brexit.

Gladstone was right about Ireland

Eugenio Biagini, Professor of Modern and Contemporary History

In the lifetime of Prime Minister William Gladstone (1809-1898), more than a million Irish people – British subjects, that is – died of disease and starvation during the Great Famine of 1845-52, and millions more emigrated over the following decades. Moreover, despite mass emigration, the domestic conditions of Ireland remained unsettled, with land agitation and a resurgent nationalist movement demanding major concessions from London.

Gladstone devoted the last part of his career to two issues: land reform and home rule in Ireland – that is to say, devolution. As he memorably remarked: “We are bound to lose Ireland in consequence of years of cruelty, stupidity and misgovernment and I would rather lose her as a friend than as a foe.”

Yet, he was dismissed by his adversaries as a charlatan and by many modern historians as both delusional and selfinterested. At the root of these attitudes there was an assumption that in so far as Ireland was ‘a question’, it was a nuisance, something on the margins of British history, and no serious politician could waste his time with its demands. So, in the 19th century, there were all sorts of reasons why enemies of change would dislike Gladstone, especially after he adopted a series of radical reforms between 1881 and the end of his career.

And then, of course, the focus of his attention – the Irish – were seen as characters who should be kept at safe distance. They were usually caricatured as brutal, incorrigible, semi-criminal types or stage Irishmen – amusing but quite helpless. Entertaining, even, but not to be taken seriously. And Gladstone seemed to engage with them as if they were people deserving of the same amount of attention as the inhabitants of London did.

Today, a similar attitude has survived among the educated elite. Gladstone saw the horrors of the Great Famine in his lifetime. And during the 20th century, the British public witnessed two civil wars in Ireland – 1916-1923 and 1968-1998 – that brought death and destruction to thousands of British subjects. During the 30-odd years of violence in Northern Ireland, euphemistically called the ‘Troubles’, nearly 3,600 people lost their lives, the largest number of UK nationals killed in warfare since the Second World War.

Given the continuing relevance of these issues, you would expect the academic establishment in this country to be seriously concerned about them. Instead, just as in the days when Gladstone’s detractors mocked his political proposals, Ireland is still externalised and quarantined – as if it were something we can somehow expel from our understanding of ourselves.

Ireland is not yet seen as a vital part of British history, in the way we are now thinking of the British Empire as part of ourselves and our collective past. And that is why there is a knowledge gap which affects our present-day policy making as much as our understanding of the historical development of the United Kingdom.

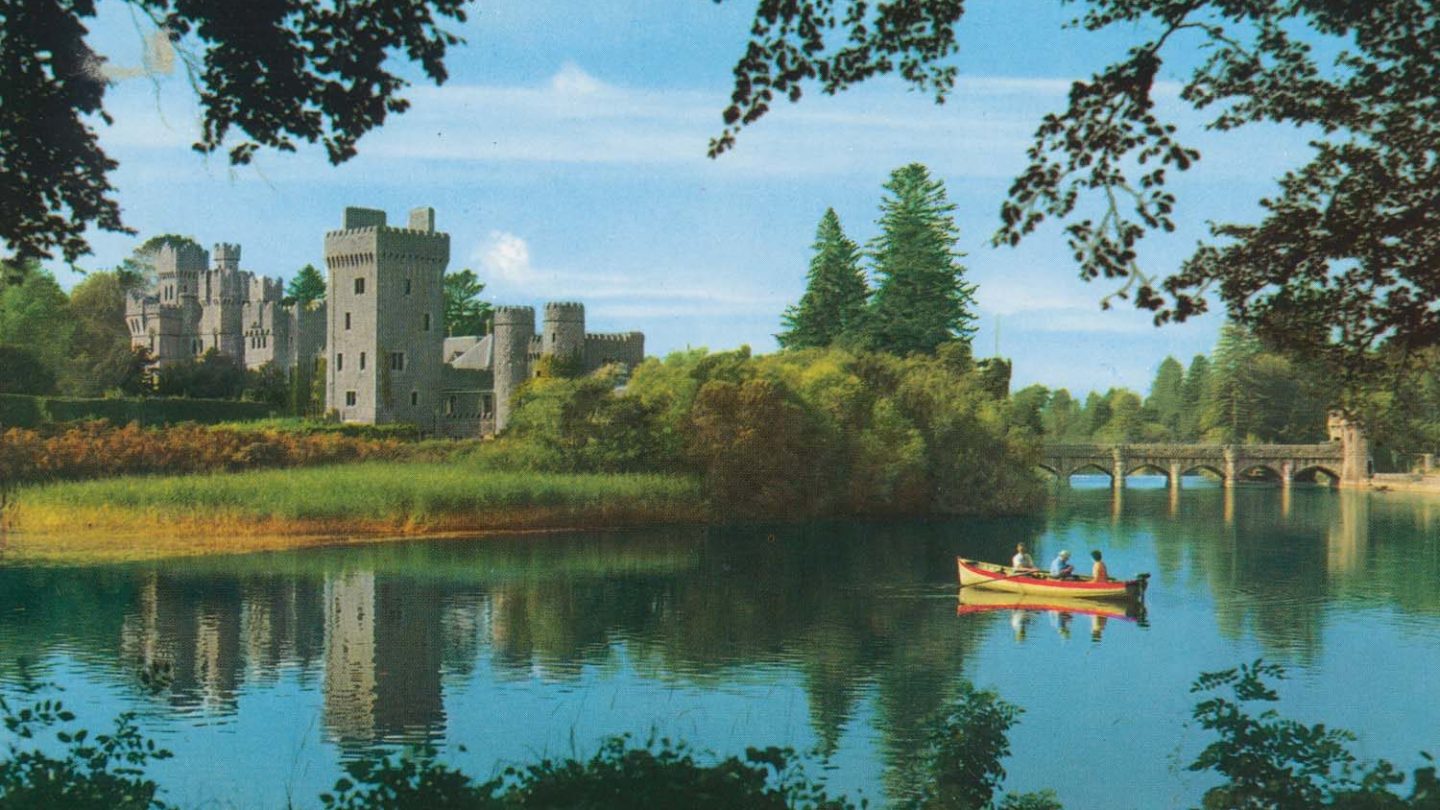

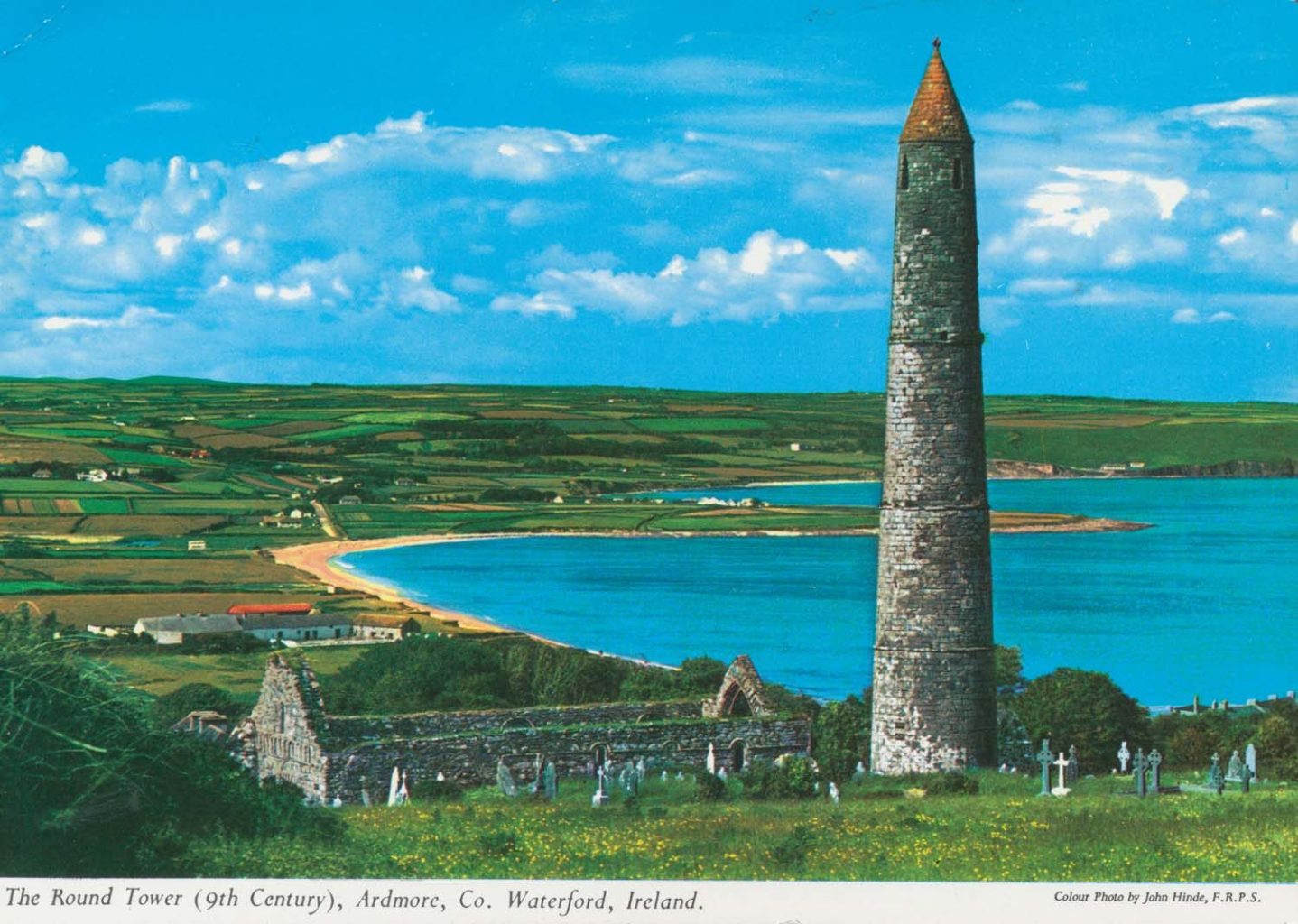

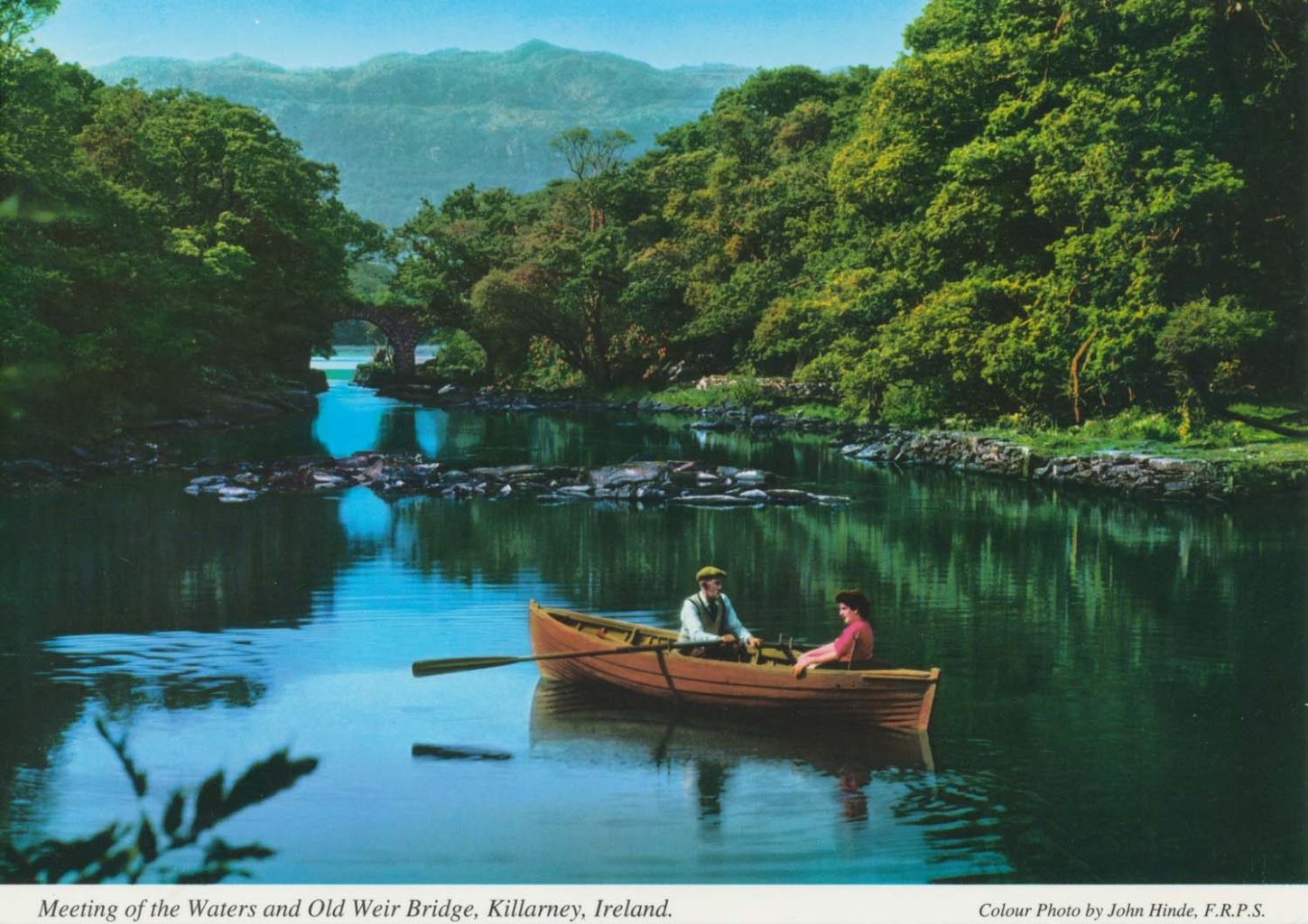

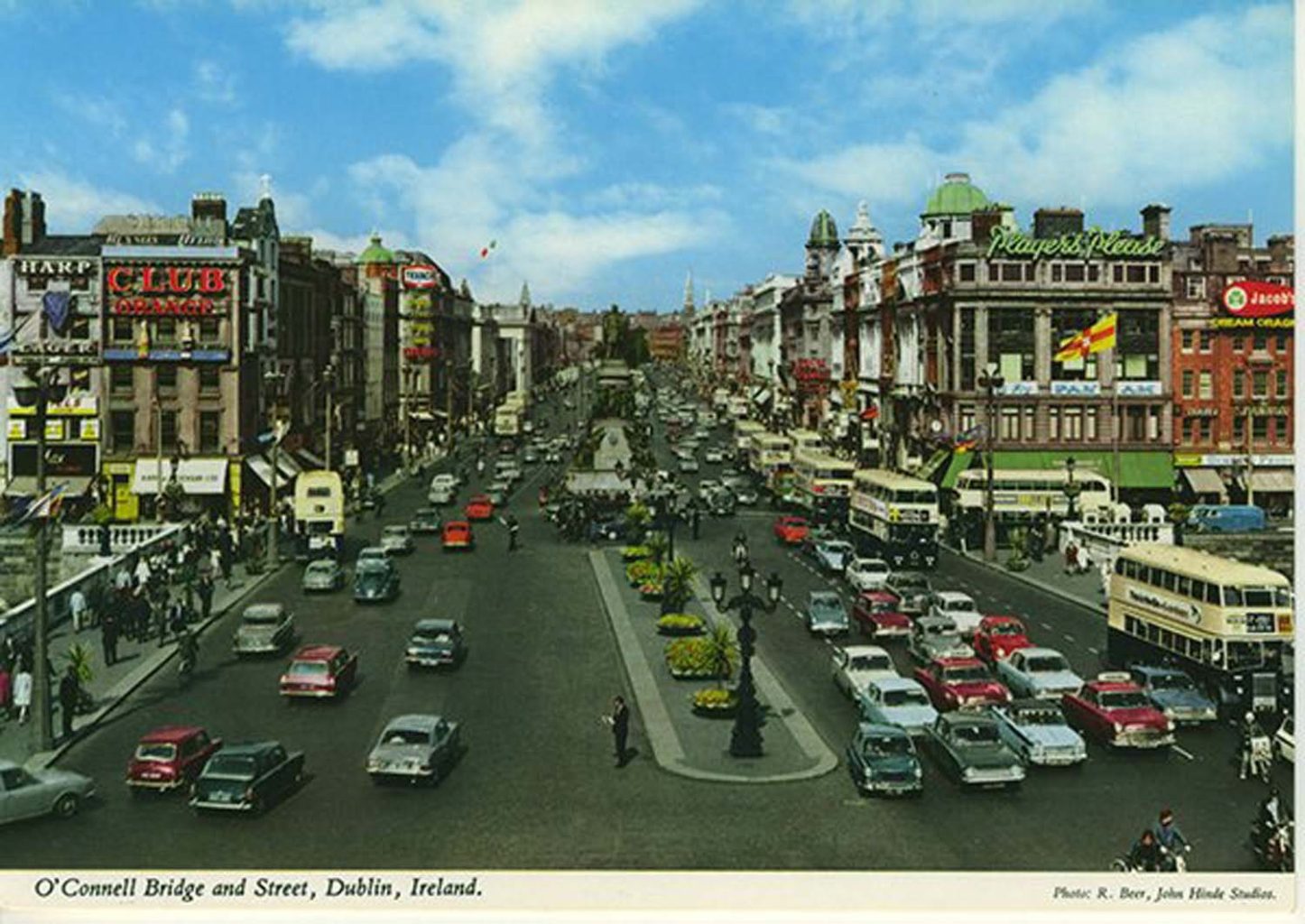

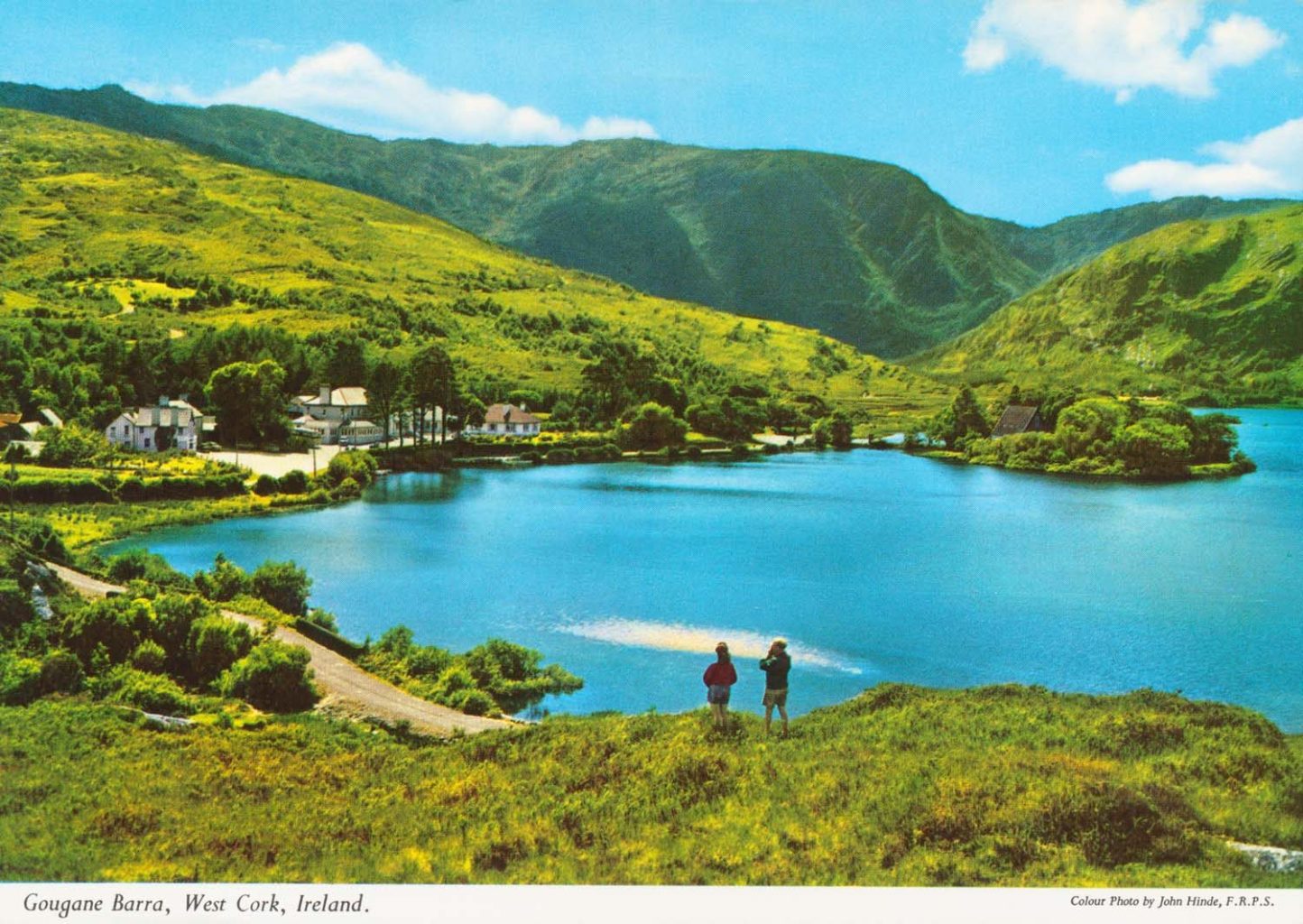

John Hinde (1916–1997)

Hinde was an English photographer who began taking photographs while travelling around Ireland with a circus. His idealistic and nostalgic photographs capture the vividness of the Irish countryside, blending Irish stereotypes with the lush, seemingly endless, landscapes. Images: The John Hinde Archive / Mary Evans Picture Library.