All in the best possible taste?

When is it OK to laugh? Who gets to make the jokes? When is enough? What is never funny? Modern comedy might tussle with what is and isn’t appropriate, but it’s got nothing on the 18th-century Great Laughter Debate.

When Oscars host Chris Rock made a joke about actor Jada Pinkett’s alopecia at last year’s Academy Awards, it concluded not with a punchline but a slap – thrown at Rock by Pinkett’s incensed husband, Will Smith. The incident made global headlines. Was the gag funny or offensive, the world wanted to know. Was Smith justified in lashing out? Should Rock have joked about such a sensitive subject?

Sadly, no one at the time was citing an obscure yet fervent British debate of nearly three centuries earlier that might have provided answers. Known as the Great Laughter Debate, it was a moment in the early-to-mid 18th century when questions of how humour worked, when it should be deployed, by whom, and to what purpose became the focus of public fascination and literary and philosophical discourse.

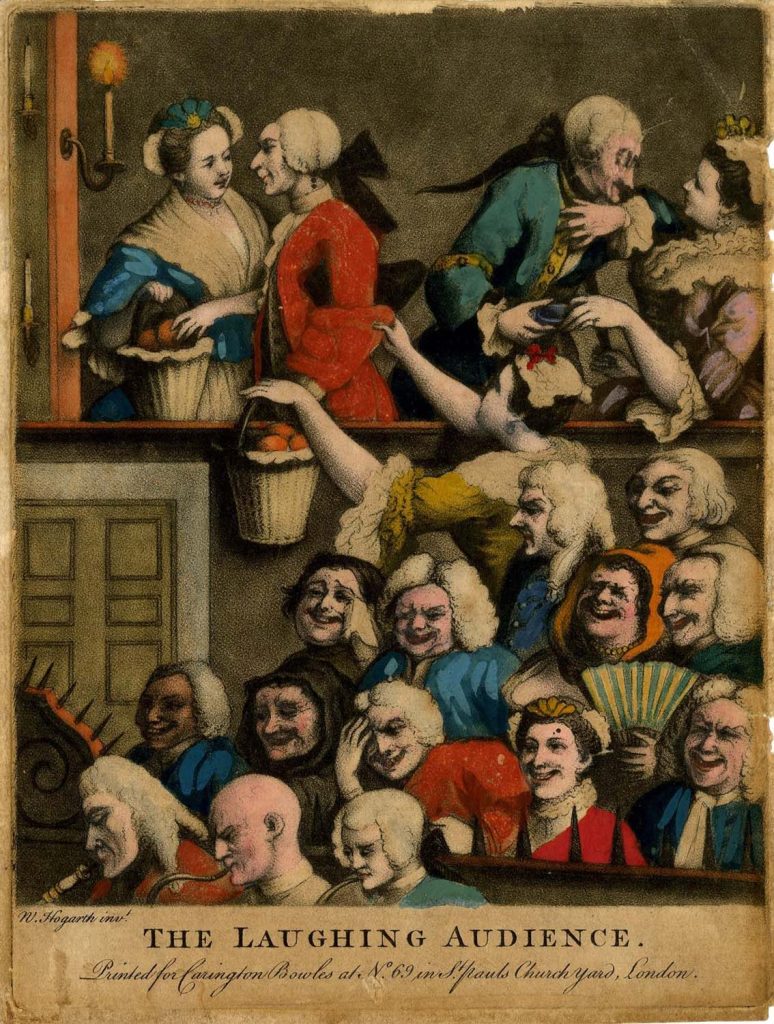

Hand-coloured mezzotint with etching. “Printed for Carington Bowles at No. 69 in St. Paul’s Church Yard, London.”

Image: The Trustees of the British Museum

“These decades are a more complex and much darker period than people often imagine,” says Dr Rebecca Anne Barr, University Lecturer in English and Fellow of Jesus. “There exists this Bridgerton fantasy of a polite and genteel era, partly because people are obsessed with the aesthetics of the country house and the beautiful paraphernalia of lives of luxury. But that’s not the full texture of the time. It’s an age of the rise of the public sphere, of satire and political debate, and of essays on social conduct and politeness. And once you start to read outside the canon of literary texts, you find coarse, violent, and deeply impolite and cruel forms of humour.”

Image: Patricia Pires Boulhousa

It’s a period of turmoil. The beginning of the century had seen a new royal dynasty, with the accession of George I in 1714. “The arrival of the Hanoverian monarchy is a paradigm shift,” says Barr. “It used to be called the ‘bloodless revolution’ – though in truth, plenty of blood was shed, not in England but in Scotland, Ireland and elsewhere. By the middle of the century, we’ve entered a period of public anger that really speaks to our current moment. There’s concern about corruption, a perceived collapse in public morality, and a sense that all these things contribute to a worrying social malaise.”

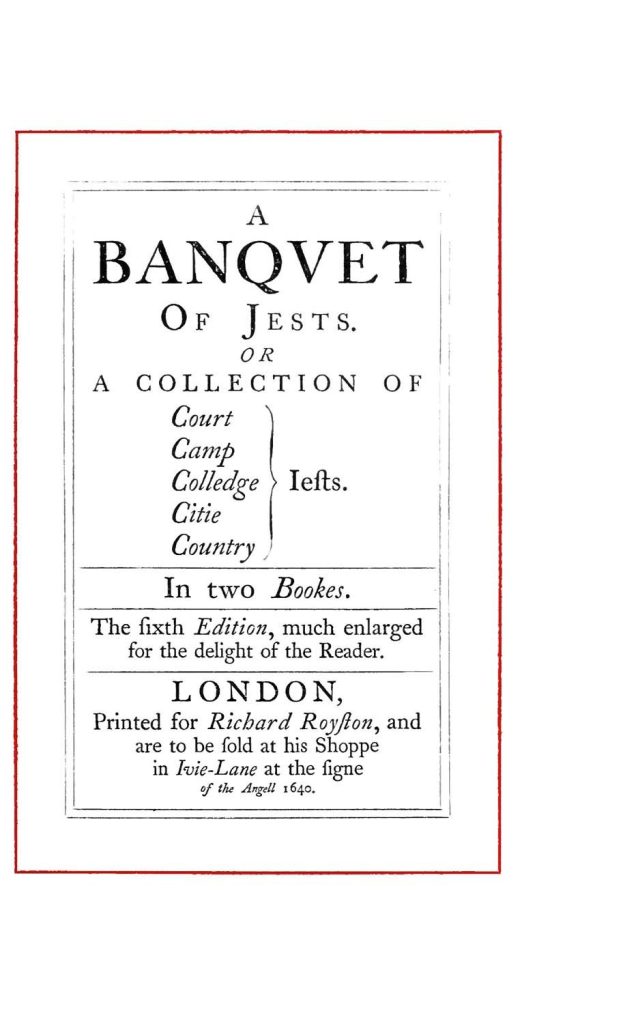

That unease and concern is voiced in a remarkable array of ostensibly comedic literary and artistic forms, for both private and public consumption. Alongside witty novels and ingenious variety shows, are farces, jestbooks and savage satirical cartoons. “The jestbook is a compendium of the underbelly of humour,” explains Barr. “The jokes in them can be silly and ridiculous, but also deeply cruel. This is playground humour, with fight and bite. They contain jokes laughing at minority accents, at disabilities, and at women’s incapacities and vanities.”

Jestbooks are not dissimilar to how memes work nowadays. Memes can repurpose images and tropes – you insert whoever you’re laughing at into a meme and turn humour against them

Jestbooks could be enjoyed privately but were also intended to be read to others. Literacy had surged during the preceding decades, and while it was still centred in the male middle classes, it was probable that in a community or labouring gang, at least one person would be able to read. “Reading aloud was an art – the reader would put on funny voices and perform,” says Barr. “In their topicality, these jestbooks are not dissimilar to how memes work nowadays. Memes can repurpose images and tropes – you insert whoever you’re laughing at into a meme and turn humour against them. More than merely ways of laughing at others, they can become powerful political tools.”

First published in 1630, the book was so successful that it was reprinted 16 times during the 17th and 18th centuries, often with additions and revisions. Images: Library of Congress

And politics was at the dark heart of how laughter was understood in the 17th century, in the overbearing figure of philosopher Thomas Hobbes, whose works propounded unsparing insights into human nature and civil society. “The definition of humour advanced by Hobbes in his most notorious work, Leviathan, was influential and disturbing,” notes Barr. “He thought laughter was about hostility and antipathy, almost a state of war. He advanced a theory that humour is rooted in superiority – you laugh at someone and have this momentary feeling of elation, vaingloriousness, thinking yourself better than them.”

The Earl of Shaftesbury, who wrote droll and gentle humour, saw laughter as a test of truth – if you mock somebody it’s not necessarily that you’re a monster, you’re simply trying to get at what’s true

By the early decades of the 18th century, Hobbes, dead for almost half a century, still had cultural cachet. “He was ‘the Monster of Malmesbury’, a figure people knew even if they hadn’t read him, who was believed to hold horrible, materialist ideas about society,” says Barr. But by way of reaction to the long Hobbesian shadow, writers and thinkers were now seeking a more complex and benevolent theory of laughter. “They were exploring the notion that laughter can come from surprise, the sight of something that reveals incongruity and absurdity. As such, laughter wasn’t hostile or pernicious, it was almost a form of recognition.”

“My wife and Mercer and I away to the King’s playhouse… But one of the best parts of our sport was a mighty pretty lady that sat behind us, that did laugh so heartily and constantly that it did me good to hear her”

Diary of Samuel Pepys, 16 September 1667.

One of the earliest proponents, perhaps precipitating the Great Laughter Debate, was Francis Hutcheson, an Ulsterman who went on to become Professor of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University. His 1725 essay, Reflections Upon Laughter, originally penned as letters to a Dublin journal, was responding in part to the negative tradition of laughter. “You had philosophers who were discussing laughter, sociability and how we get on with other people,” says Barr. “The Earl of Shaftesbury, who wrote droll and gentle humour, saw laughter as a test of truth – if you mock somebody it’s not necessarily that you’re a monster, you’re simply trying to get at what’s true.”

If laughter truly is part of the human condition, what does that tell us about us?

These early analyses and counter-theories sparked wider reflection. “Laughter became a recurrent topic,” Barr explains. “Popular periodicals like The Spectator were discussing the nature of humour and the limits of polite mirth in the theatre and public life more generally. There was an acknowledgement that there is a peculiarly English humour – something in the soil, or the people, that means we laugh at things in a particular way.” In the wake of philosophical discussion about consciousness by thinkers such as René Descartes and John Locke, people were pondering what laughter suggested about humanity. “If laughter truly is part of the human condition, what does that tell us about us?” says Barr.

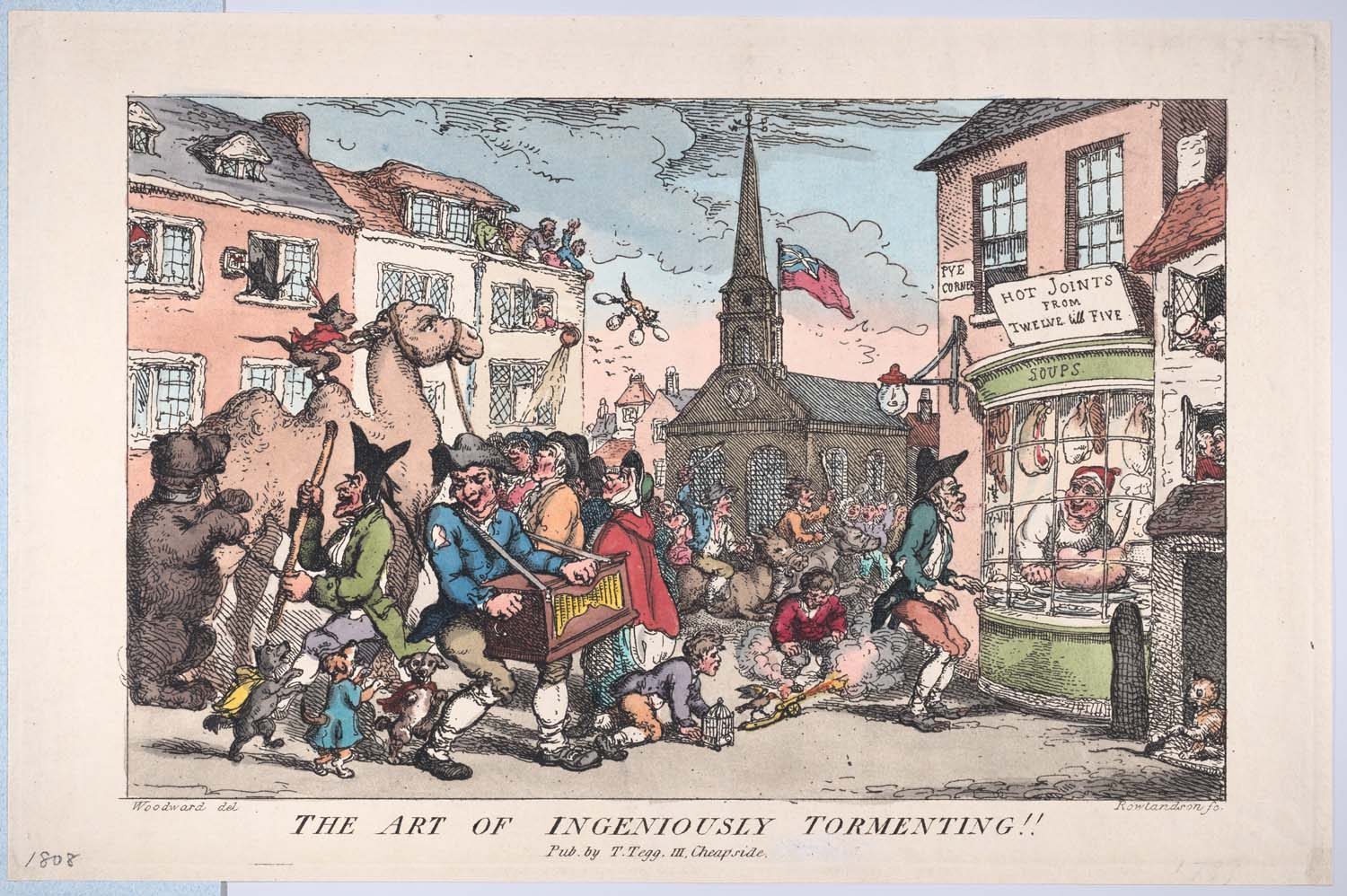

Etched by Thomas Rowlandson and inspired by the novelist Jane Collier’s satirical book giving advice on how to nag.

Image: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Some of the most trenchant contributions to the Great Laughter Debate came not from theoreticians and philosophers of humour, but practitioners – in particular, the comic novelists we think of as defining this era. Perhaps the best known is Henry Fielding, author of The History of Tom Jones, and of Shamela, a parody of Samuel Richardson’s pious tale of virtue, Pamela. “Henry Fielding believed one of laughter’s virtues was its deflation of pretension and affectation,” says Barr. “He saw it as a ‘natural’ part of an embodied experience and a dimension of shared humanity – a communal pleasure that he wants to redeem from mid-century moralists like Richardson.”

The gendered preconceptions around what gets defined as funny is still an issue today. When literary critics go back into the archive, they sometimes lose their sense of humour

Less well known today but just as significant, Barr believes, are Henry’s sister Sarah Fielding and her friend and fellow author, Jane Collier. Barr’s upcoming research project as the Crausaz Wordsworth Interdisciplinary Fellow in Philosophy will examine the participation in the Great Laughter Debate of Collier, Fielding and other female writers, including Eliza Haywood and Frances Sheridan. It will ask how the philosophy of laughter might look different if studied in novels by women.

“I may therefore conclude, that the passion of laughter is nothing else but sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others”

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651.

“The gendered preconceptions around what gets defined as funny, which these women were exploring at the time, is still an issue today,” Barr points out. “When literary critics go back into the archive, they sometimes lose their sense of humour. Sarah Fielding is an example of an author who has suffered from the presumption that men are funny and women aren’t; that men are interested in laughter and women aren’t. People almost automatically presume she’s always serious rather than tongue-in-cheek.”

Collier wrote a popular ‘anti-conduct’ book titled The Art of Ingeniously Tormenting, a guide to making the lives of your nearest and dearest an absolute misery. “You read about the horrible things people do – the banality, the vanity, and you recognise them, and have a good laugh,” says Barr. And Eliza Haywood wrote “brutally funny books that are also really dark”, penning yet another satirical response to Richardson’s Pamela, titled The Anti-Pamela; or Feign’d Innocence Detected, which offers up uneasy laughs and a prickling awareness of your own complicity in a hypocritical society.

“Keep up in your mind the true spirit of contradiction to everything that is proposed or done; and although, from want of power, you may not be able to exercise tyranny, yet, by the help of perpetual mutiny, you may heavily torment and vex all there that love you”

Jane Collier, The Art of Ingeniously Tormenting, 1753.

Sarah Fielding’s final novel, The History of Ophelia, contains what one scholar of humour has called “the most unexpected rape joke in 18th-century women’s writing” – an extended joke about the attempted assault of an elderly woman. Barr describes it as “very Benny Hill, played for laughs”, yet it’s plain, she says, that Fielding is attempting something serious with this farcical scene. “It’s funny… but. It works as a caveat and a warning about the lack of moral authority, given that the would-be rapist is a justice of the peace, and if you made a rape case allegation you’d go to a justice of the peace. The genre of the rape joke is horrific, but it’s being used in a really interesting way here to unpick power, teaching us to recognise things about ourselves, society and authority.”

At moments of cultural transition, especially moments of cultural conflict, laughter becomes more powerful

Can the Great Laughter Debate teach us things today? Barr believes so. “At moments of cultural transition, especially moments of cultural conflict, laughter becomes more powerful. We are in a waning economy, where inequality is widening and society has become more bitter and seemingly irreconcilable, as in the 18th century. The polarisation of public discourse means laughter is again contentious – we are self-conscious about what we laugh at, and whether we are even ‘allowed’ to laugh.”

Yet if laughter is a way of highlighting divisions and dissatisfactions, Barr believes it is also worth considering whether laughter can work in an ameliorative, consensus-building way. Right now, she concludes, “it’s a good time to think about what we find funny, and why”.