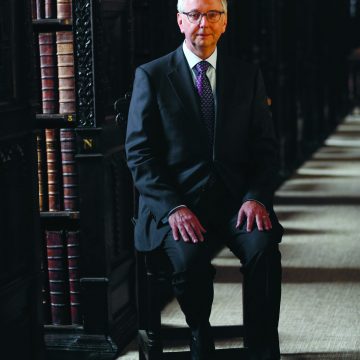

Leading from the front

As Vice-Chancellor Professor Stephen J Toope hands over the reins, he reflects on his time guiding the ‘highly charged, intellectually exciting and enriching place’ that is Cambridge.

When Professor Stephen Toope first set foot in the oak-panelled office of the Vice-Chancellor five years ago, the world looked a very different place.

The consequences of Britain’s growing political polarisation were not fully realised. The UK government was actively encouraging universities to engage with China. The global pandemic was a horror as yet unimagined. Each of these issues would make its mark, in one way or another, on Toope’s tenure at the helm of the University.

Reflecting, in that same room, on his period in office, the Vice-Chancellor notes that the disruption of the past few years has had some unexpected upsides. “One of the things I have been most impressed by is the collegiate University’s resilience. During the pandemic, staff and students adapted to ever-changing pressures. Academic and support staff were able to successfully switch teaching and assessment online, rearrange timetables and reimagine research.”

In adversity, he says, Cambridge found ways of improving the way it did things. It has been, he says, a “very, very demanding time”. Yet along with the relentless challenges – including shifting geopolitics and national disputes over pay and pensions – the past five years have offered great opportunities for the University to reinvent itself.

For all the turbulence, Toope is proud to have left his mark on an 800-year-old institution. Under his leadership, the University made unprecedented progress in attracting and supporting hundreds of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. The ongoing £500m Student Support Initiative continues to draw impressive philanthropic support. The rapper, Stormzy, helped highlight the opportunities of Cambridge to a whole generation of black students, helping to treble the number of black undergraduates in only two years.

Cambridge is demonstrating a commitment to serving every level of society

The Vice-Chancellor believes that Cambridge, so often accused of elitism, is now clearly demonstrating a commitment to serving every level of society. “Being outstanding is ultimately about being elite. But just because you are outstanding does not mean you need to be elitist. I have come across scores of people, including professors and senior researchers, who are the first people from their families to attend university.

“Public universities are really important to the UK. People don’t get in because they have money or connections. But I do worry sometimes that when you are in such a highly charged, intellectually exciting and beautiful environment that is as enriching as Cambridge, we could very easily look inward. We do need to constantly challenge ourselves to remember that we are a great public university that exists to serve the nation and the world.”

Philanthropy, he believes, is key to delivering outstanding performance. On his watch, the £2bn ‘Dear World, Yours Cambridge’ fundraising campaign hit its target ahead of schedule, underpinning vital research and enhancing the University experience.

Universities are under an unprecedented level of scrutiny

New initiatives have been launched designed to deliver lasting real-world impact in tackling global problems: Cambridge Zero is leading the search for solutions to the climate emergency; AI@Cam will exploit the potential of artificial intelligence; and it is hoped that a renewed focus on the detection, treatment and prevention of cancer will deliver life-enhancing results.

Behind the scenes, there has been a relentless drive to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of professional services – the beating heart of the University administration – by streamlining operational areas that had grown up piecemeal over many decades.

The rapidly changing national political landscape has brought its own pressures. Universities are under an unprecedented level of scrutiny, which plays out in lurid headlines and regulatory intervention. Not all of it, says Toope, is helpful: “More and more regulatory obligations are being imposed which are in danger of eroding the autonomy of universities. Autonomy is central to academic freedom and to the ability of a university to challenge received wisdom where necessary.”

The Higher Education sector has found itself over the past two or three years caught up in the ‘culture wars’ stoked by politicians across the spectrum. In Cambridge, among other things, that has prompted accusations that the University was somehow attempting to limit freedom of speech and that it had become over-reliant on financial support from China. Toope disputes both contentions strongly but concedes that external scrutiny is important. “There is no problem with people advocating for genuinely free inquiry and, of course, freedom of speech. Universities must be bastions of both. If we aren’t, we are failing in our core mission.

“But it feels like in both the US and the UK there is a certain political manufacturing of elements of the so-called culture wars that serves purposes having nothing to do with free inquiry or free speech, and is attempting to drive wedges for partisan political purposes.

“In any community, there is always a balance to be struck between freedom and autonomy on the one hand, and equality and social cohesion on the other. How do you balance those imperatives? I treasure our ability to have that debate; that’s the debate we should be having. What I don’t treasure is name-calling and false conflicts promoted by some in the media and by some political commentators. That just distracts from the real debates we should be having within society.”

The Vice-Chancellor is equally vehement in opposing the promotion of science and technology at the expense of arts and the humanities. It is simplistic and unnecessarily divisive, he says, to attempt to play one off against the other. “There is no doubt about the importance of the STEM subjects and maths. We need more people in the public service and in Parliament with knowledge of science and technology. I’m a lawyer and, historically, there have been lots of lawyers in public life and not many people with science and technology backgrounds.

“But, of course, we also need to better understand human society, human motivation, human behaviour and human inspiration. There cannot be a society that says all that matters is STEM education and research. And there can’t be a society that says all that matters is the humanities or the arts. If you think about climate change, for example, it’s clear that you have to change human practices and human expectations. You need to learn from behavioural insight. We also need art to challenge ourselves to imagine different futures.”

University education is more than simply a route into work

And he is clear that a university education is more than simply a route into work. “You should not measure the university experience solely on the basis of the job opportunities that present themselves when you graduate,” he says. “We are looking at a world where careers are changing and shifting all the time. We should be creating educational opportunities that allow people to make the changes they need to meet the complexities of that changing world.”

Though characteristically upbeat, he does not want to make light of the disruptions caused by the pandemic: “I thought, coming in, that I would have the opportunity to range across the University meeting colleagues and finding tremendous inspiration in an institution with such global impact. I was relishing the opportunity to meet alumni and supporters around the globe, and to hear about the affection they have for their College and the University. I looked forward to immersing myself in the cultural and sporting life of the University.

“I made a good start on all of this in my first years, but it came to an end rather abruptly with Covid. Happily, as we move out of the pandemic, life is returning to something more like normal – the choirs are singing evensong in College chapels, the Boat Race was back on the Thames, the University is once again flourishing.”

As Toope contemplates a return to his native Canada, he is clear that Cambridge’s innate strengths can help it maintain its relevance in that rapidly evolving world. The College system, he believes, provides an experience for students and staff almost unrivalled elsewhere in Higher Education. That in turn fosters a spirit of inquiry which underpins education and research.

Cambridge is unique in the scale of its ambition and intellectual capacity

“There is a tremendous intellectual curiosity and ambition here. Our colleagues really want to be world-leading in their fields and work really hard to understand the world better. Of course, all research universities might say that, but Cambridge is unique in the scope and scale of its ambition and its insatiable intellectual capacity. That is what makes it one of the top universities in the world.”

Cambridge is likely to be his last role as Vice- Chancellor, completing 13 years as a university leader following a long spell at the University of British Columbia. An eminent international lawyer by background, he was recently announced as the next CEO and President of the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research, located in Toronto, where his family is based.

With the process of choosing a new Vice-Chancellor now under way, what piece of advice would he offer his successor? “Every Vice-Chancellor has to find their own way because times change. But I would say: remember that you are a trustee of a great social and educational institution that has persisted and strengthened over 800 years. The real goal is to make a contribution that positions Cambridge to be just a little bit better than when you arrived.”