‘To understand society, you have to make human relationships, rather than structures, your focus’

Professor Stephen J Toope, the Vice-Chancellor of the University, reveals the reads which have had the greatest influence on his life

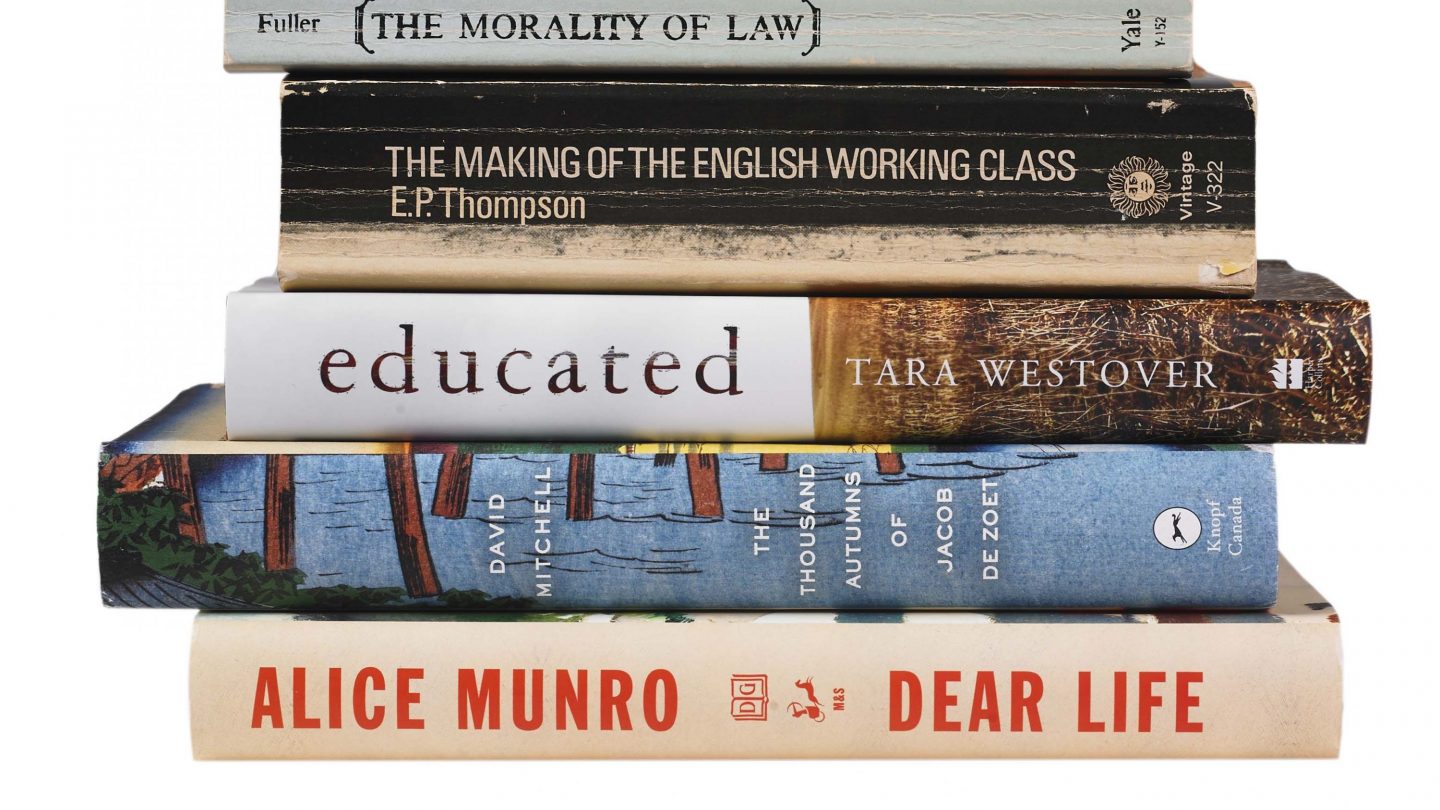

Vice-Chancellor, Professor Stephen J Toope (Trinity 1983), is an avid reader; as a consequence, he says that selecting titles for Shelfie proved rather challenging. So it is fascinating to note that, from the ability of humans to shape their laws to a quest for self-identity in a vastly unfamiliar world, Professor Toope’s choices have one thing in common: the championing of the humanity of individuals. “To understand society, you have to put human interrelationships, rather than structures, as the primary focus of your attention,” he says. That philosophy has informed his long career in international law and human rights – and is a theme reflected on his bookshelves.

-

1. The Making Of The English Working Class

EP Thompson (Corpus 1941)

I first read this while studying English History and Literature at Harvard. Thompson says his subject is not social structures, but a description of human relationships. I was deeply influenced by Thompson’s understanding of how power can be used as a kind of symbolic or theatrical element to exert control within society. Again, he showed that the way power functions is often not purely structural but also through relationships, and that those relationships can be themselves shaped by examples of what he called ‘the theatricality of the law’. I thought I was just interested in social history, but it turned out I was actually interested in legal history, and I didn’t know it. And that’s how I ended up going to law school. Vice-Chancellor, Professor Stephen J Toope (Trinity 1983), is an avid reader; as a consequence, he says that selecting titles for Shelfie proved rather challenging. So it is fascinating to note that, from the ability of humans to shape their laws to a quest for self-identity in a vastly unfamiliar world, Professor Toope’s choices have one thing in common: the championing of the humanity of individuals. “To understand society, you have to put human interrelationships, rather than structures, as the primary focus of your attention,” he says. That philosophy has informed his long career in international law and human rights – and is a theme reflected on his bookshelves.

-

2. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet

David Mitchell

I read this during a bout of sickness on holiday. Instead of being out swimming in the lake, I was lying in bed. I had time on my hands, and I was absolutely enraptured by this book. It tells the story of a Dutchman in Japan managing the accounts of the Dutch East India Company, and it explores how layers in different societies can have almost no interaction. The central character, Jacob de Zoet, finds his way into these different societies during the course of the book – and it doesn’t go very well. I think culture has a profound shaping ability that means that people look at the world differently, but this is not a happy story about cultural interaction! Instead, it’s a story about failing to understand cultural difference. And I find that fascinating.

-

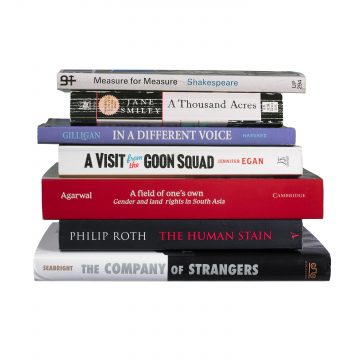

3. The Morality of Law

Lon F Fuller

This, for me, is one of the most important books in 20th-century legal theory – I came across it while I was at law school. The book is really part of a debate between Fuller, who was a professor at Harvard at the time, and HLA Hart, who was a logical positivist at Oxford. Hart argued that law acquired its authority as a result of hierarchy and process – and at the time he won the debate. But I find Fuller to have the more satisfying argument. He believed that law was not about particular social institutions but emerged through the interaction in society of people and groups. His argument allows an internal critique of the law on grounds of fairness, and he allows for individuals to be actors – not passive recipients of the law or victims. In international law and human rights – where it is often not clear which authority or hierarchy should be referred to – the idea that law emerges, in part, from a human sense of right and wrong is critical.

-

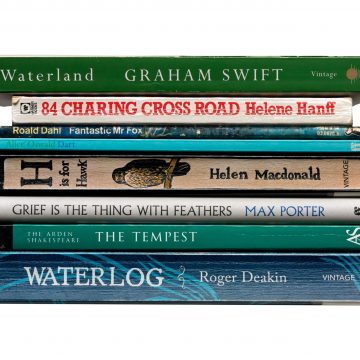

4. Educated

Tara Westover (Trinity 2008)

When I arrived here, Barry Everitt, Provost of the Gates Trust, sent me a signed copy of Tara Westover’s book. I started to read it on a weekend, and I just could not put it down. I found the story itself so powerful. But what is so moving about it is the almost complete absence of bitterness. Her life is filled with these difficult moments that are worthy of extraordinary anger and frustration and even hatred – and yet there’s none of that in the book. In fact, if anything, what amazed me was this sense that she captures her love for where she came from. It could be a didactic book: a story about overcoming a difficult background. But it’s so much deeper than that because it’s challenging to herself, and her own notion of identity.

-

5. Dear Life

Alice Munro

I first read this in high school, when I was around 16. At that time in my life, I was just exploring the world and trying to understand it. And boy, if there’s someone who can help you understand the world, it’s Munro, even though she’s talking about very small places and, sometimes, very narrow lives. But I just keep going back to her. Her writing is so economical and so crystalline: it just conveys so much. She is so good at capturing the moment when something shifts and changes in life and makes a person understand himself – usually herself in Munro’s writing – differently or understand the world differently