Fuelling success

The Gates Cambridge Scholarship programme is celebrating its 20th anniversary. Or, to put it another way, this year Cambridge celebrates the international students and scholars who come here – to change the world.

In June 2009, Bill Gates Sr was asked, during an interview for the Commonwealth Club of California, if witnessing the work of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation had ever left him speechless. Gates, a lawyer of vast experience, considered the question. “I wonder if I’ve ever been speechless,” he said, to a murmur of amusement from the audience. “Whatever the positive emotion is, without possibly reaching speechless, every year I make a trip to Cambridge University in England and visit with 250 graduate students who are there on our ticket.”

He paused, visibly moved. “I may be speechless … It is awesome. You would love to see it … Young people who have had a magnificent college education, been through a competitive selection process – you don’t have to think for long to have a very clear view of what I’m talking about. They are from everywhere, that’s part of the attraction. And, by and large, they are going to go back to the places where they came from to be significant influences. That’s a week I cherish greatly.”

In September, Bill Gates Sr died, having enjoyed the successes of Gates Cambridge Scholars over a period of some 20 years. The programme was founded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation with a $210 million donation, the largest single donation to any UK university. In those two decades, the programme has awarded almost 2,000 scholarships to scholars from 700 universities, representing 111 countries.

And while Gates Cambridge Scholars often go on to extraordinary academic careers, they also commit to improving the lives of others, using everything from discoveries on the cutting edge of science to projects that drive social justice and societal change. The programme creates an environment in which scholars can focus on their research – but many also develop their own projects. Jennifer Jia (Girton 2017, PhD Clinical Neurosciences) came to Cambridge as a Gates Scholar to study brain regeneration following neural damage. But alongside that work, she has created Emporsand, an enterprise that uses fast-fashion remnants to create sanitary pads, tapping into concerns around waste, the environment and period poverty.

“They do everything they can to push the boundaries,” says Professor Barry Everitt, Provost of the Gates Cambridge Trust and former Master of Downing. “Because that’s where sparking creativity comes from.”

Scholars define how they will improve lives. It could be running an NGO, working inside government – or becoming an expert in Anglo-Saxon who will inspire future generations

For Professor Vitor Bernardes Pinheiro (Churchill 2006, PhD Biochemistry), now group leader and lecturer in Synthetic Biology at the Rega Institute for Medical Research in Leuven, winning a Gates Cambridge Scholarship gave him the freedom to explore what he calls “crazy ideas” and take risks. His doctorate looked at how the bacteria Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (progenitor of the bubonic plague) interacts with insect cells to quickly evolve (research he continued at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology). To date, Pinheiro has demonstrated that the requirement of life for DNA and RNA were an accident (“They were better than anything around at the time, but they are not the only materials that can store genetic information”). Now, he is working on how protein evolution works and on drastically accelerating drug development via XNA aptamers – nucleic acid polymers that could, in theory, act like antibodies to fight disease. “I don’t think I would have got here by any other path,” he says. “For me, it was transformational.”

Diversity – of thought, of background, of nationality – drives creative thinking across all fields, and for all students, and Gates Cambridge Scholars bring their talents from all over the world. But for those whose home countries have been torn apart by conflict, the achievement is even more remarkable. “Our talented graduate students include those from places such as Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq,” says Everitt. “It is very likely that they would not otherwise come here, because there wouldn’t be funding for them. They bring academic excellence to the University, but they also enrich the University through their diversity and the other things they do that are visible on the world stage.”

Professor Thabo Msibi (Pembroke 2009, PhD Education) is, today, at the pinnacle of an illustrious academic career. He is Dean of the University of KwaZulu-Natal – the youngest person ever to hold the position – and retains, he says, a deep sense of privilege from his time as a Gates Cambridge Scholar studying changing attitudes to masculinity in South Africa. “It’s very rare for somebody from my background, with my experience, to go into a space like Cambridge, fully funded on one of the most prestigious scholarships in the world. I don’t take that for granted. It means a lot and it has certainly been a major contributor to my success.”

Msibi was born in a small rural village called Ntabamhlophe in the KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa and, until he was 10, was educated at a township school. His mother had to drop out of school to work, and his father was working towards a teaching qualification, so Msibi was brought up by his aunt, and then his grandmother.

In 1994, his parents reunited and the moved to the town of Estcourt, where Msibi attended the local high school. But he found it hard to reconcile the “middle-class white life” of his school with his home life as a traditional Zulu boy. His mother worked long hours. As was normal practice in South African society, his father was not expected to take on responsibilities such as cooking, cleaning and looking after young children: that role fell to Msibi.

Struggling to cope, he developed a gambling problem. But in the midst of all this conflict, he felt a need to improve the lives of others. While still at high school, he set up a hockey club in his old township, and founded a multi-racial debating league.

After meeting a group of Christians at school, he stopped gambling and started to work. His potential was spotted, and he gained a place at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. During his teaching qualification, he was accepted for a Fulbright scholarship at Columbia. “But I found New York alienating, though it is such an incredibly diverse, inclusive and dynamic city,” he says. He applied for a Gates Cambridge Scholarship, and found something quite different.

“In Cambridge I shared a great sense of affinity and connection. Perhaps it’s the uniqueness of that institutional culture. It enables those deep connections built on mutual respect and trust. I made many friends there who I consider family. It still feels like home.”

It’s easy to see how Msibi’s work on gender and social equality directly impacts his community. But scholars find many ways to make the world a better place. “They can define how they will improve lives in whatever way they like,” says Everitt. “It could be running an NGO, working inside government, or advising government on things like climate change or public health. Or it could be doing a PhD in Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic, becoming a researcher and teacher inspiring future generations.”

By studying the great apes, our closest living relatives, Koops seeks to identify the processes that drive the use of technology across ape species – thus shedding light on what makes us human

For Kathelijne Koops (St John’s 2006, PhD Biological Anthropology), currently a Lecturer in Primatology in the Department of Archaeology, this commitment to human development goes hand in hand with her academic research. Koops works on the evolution of tool use: by studying the great apes, our closest living relatives, she seeks to identify the processes that drive the use of technology across ape species – and, in turn, shed light on what makes us human. Her Gates Cambridge experience began on a village football field in Guinea, West Africa, where she was carrying out fieldwork with a group of chimpanzees in the Nimba mountains. “I was called for my interview, and the pitch was the only place I could get a satellite phone signal!”

Eager to find a way of studying at Cambridge with pioneering primatologist Bill McGrew (now Emeritus Professor), she was also inspired by the Gates Cambridge ethos of research excellence and making a difference. Her PhD resulted in five research papers and made news across the globe with her discovery that chimpanzees use tools to cut up their food. But her long-term fieldwork in Guinea (for which the trust provided extra financial support) has helped to conserve both the chimpanzees and the biodiversity of their habitat, and won the support of the local community. “Gates Cambridge puts a lot of emphasis on asking what impact you are going to have on the world, rather than just publishing in a high-profile publication. We need to think about the bigger picture – for example, how the destruction of habitats can lead to pandemics.”

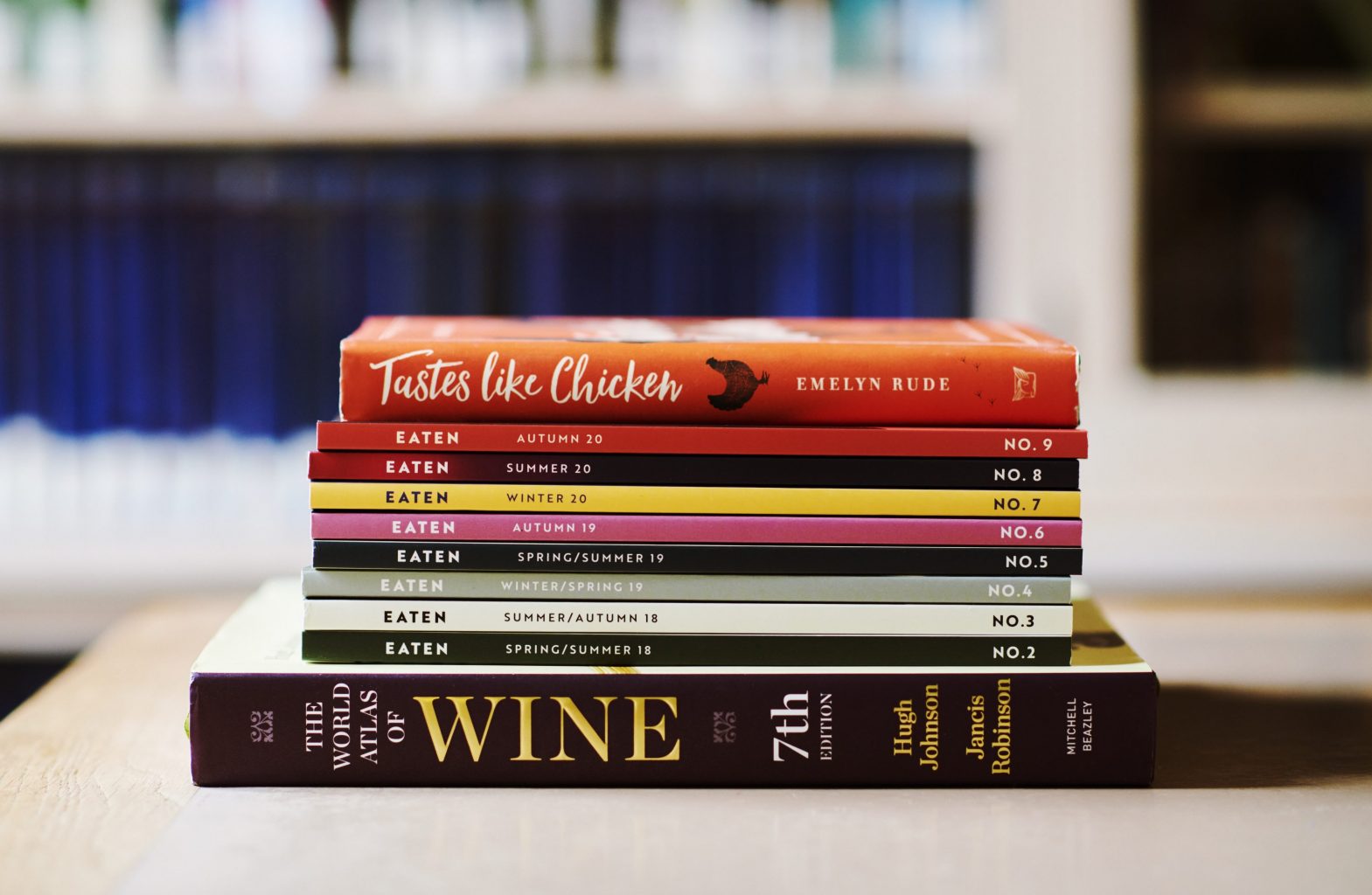

This kind of big-picture thinking can start with a very simple question. For historian and current Gates Cambridge Scholar, Emelyn Rude (King’s 2018, PhD History), that was: “Why do people eat what they eat?” Answering that question resulted in a book (Tastes Like Chicken: A History of America’s Favorite Bird), and has now led to her current area of interest: investigating how past fish stock collapses have impacted national eating habits. Like Koops, she is also passionate about the impact of climate change, and, as a keen scuba diver, what it’s doing to the oceans.

“People never really seem to tie the environment to eating habits, even though they are fundamentally intertwined,” she says. “It’s a big gap in the historical scholarship. There are historians of food production and historians of food, and nothing in between. But in England, for example, the fish used in fish and chips tracks the health of fish stocks around the country. When the cod collapsed, there was a big switch to haddock. And something like this has a lot of very subtle impacts on the food system at large. Agriculture, and animal agriculture in particular, is one of the biggest contributors to climate change and environmental degradation. It’s such a powerful economic cultural and social force, and it changes the world.”

As a Gates Cambridge Scholar, she says, she’s found a community of students who are interested in engaging with the world – and who are supportive no matter what you want to do. “It doesn’t matter if you’re a chicken historian or you’re finding a cure for cancer – Gates makes an effort to promote diversity, in all its many forms.”

So what will the next 20 years bring for the Gates Cambridge Scholarship programme? It won’t shy away from the big challenges, says Everitt. Outreach programmes are addressing the difficulty of getting students to the level of educational attainment required to apply, and making it clear that all are welcome. “We want to do more, and we want people to come from all over the world. While our current applicant pool and scholar community is very diverse, there’s always more to be done in terms of increasing access for people from different backgrounds and countries who will thrive at Cambridge. The University is strengthening links with Africa and China and is actively working to a widening participation agenda; the Trust undertakes outreach through its Ambassadors programme where scholars and alumni present the Gates Cambridge Scholarship programme at universities across the globe. We select Scholars because of their academic excellence and commitment to the programme’s values, irrespective of the institutions in which they gained their undergraduate degrees.” Facilities for Gates Cambridge Scholars are set to be improved, as well: building will shortly begin on their new centre on Mill Lane, to be named in honour of Bill Gates Sr.

And Msibi says that the impact of the programme will only become greater. “We have an incredibly attention-driven world at the moment, with fake news, alternative truths and denial of science,” he says. “I hope that Gates Cambridge Scholars will continue to play their part in advancing the value of human dignity and science. We must contribute towards building a world sustainable for the next generation. We have to try to find the means to help the world change direction.”

Meet current Gates Scholars

-

Emelyn Rude

History (King’s)

A magazine on the history of food edited by a Gates Cambridge Scholar has just been named Publication of the Year by the International Association of Culinary Professionals (IACP).

The award for Emelyn Rude’s magazine, Eaten, is part of the annual food writing and cookbook awards presented by the IACP. The group itself was founded in 1978 by a collection of cooking-school owners and instructors seeking professional support. Well-known chefs and TV personalities Julia Child and Jacques Pépin were some of the early members.

Eaten won in the category for publications printing under 300,000 copies. The magazine has only been going for a year and a half and was set up through a Kickstarter campaign. According to Rude: “I wanted to write for something that would talk about food history in an accessible way that was accurate, good history. There was nothing around.”

-

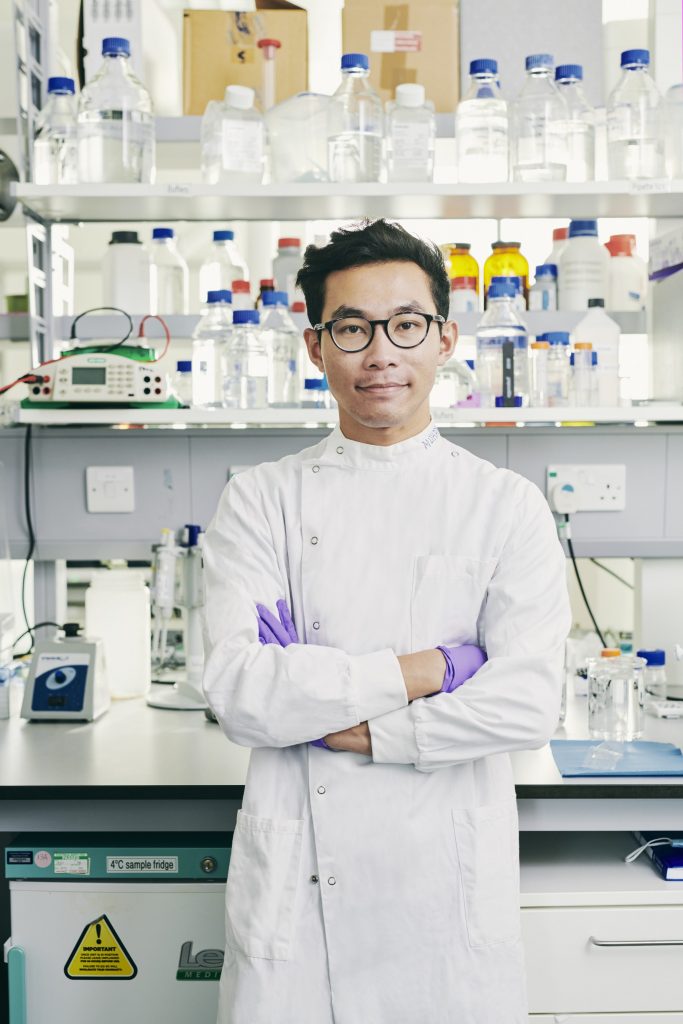

Muhamad Hartono

Chemical Engineering (Downing)

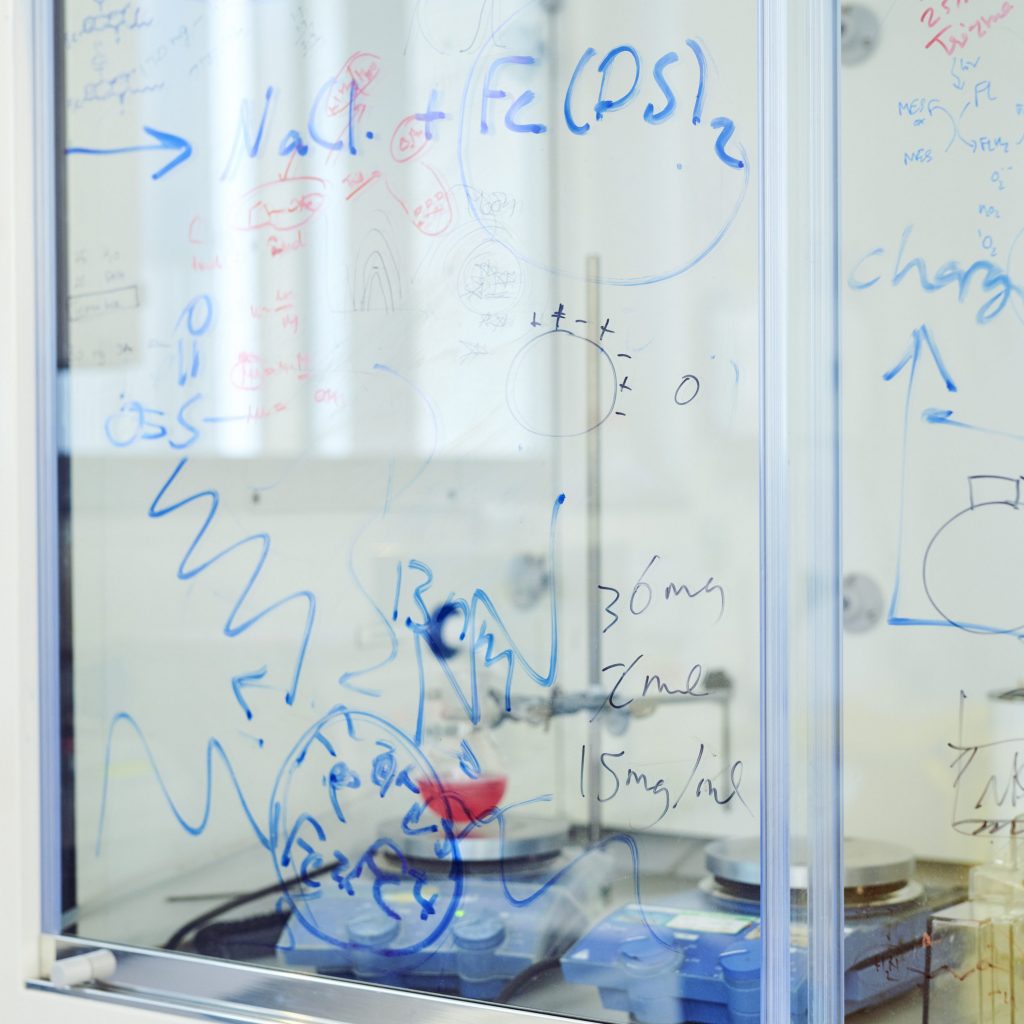

Muhamad Hartono’s PhD, which he began in the autumn, aims to design and synthesise nanoparticles that can selectively target pancreatic cancer cells and deliver anticancer drugs as well as diagnostic functionality which can improve treatment outcomes.

There is a personal motivation to his work: two years ago his grandmother died from pancreatic cancer while he was studying in the Netherlands; he was unable to travel to Indonesia to attend her funeral. “I knew I wanted to work on cancer, but I did not know initially that pancreatic cancer was so difficult to treat. Losing my grandmother made me reflect,” he says.

Initially he just wanted to get a good engineering job, but Hartono’s university experience has ignited a desire – driven by personal circumstances – to understand the wider impact research can have on local communities, such as the one he grew up in in Indonesia, and the wider world.

-

Jennifer Jia

Clinical Neurosciences (Girton)

Jennifer Jia is the founder of Emporsand, an enterprise that aims to empower women through sanitation. Its first product, a sanitary pad made from the remnants of fast fashion, taps into two of the biggest issues the world is facing today – period poverty and concerns about waste and the environment.

Jia’s background is in medicine, specifically clinical neurosciences. In 2018, she was based at the Cambridge Stem Cell Institute, located at the time next to the Judge Business School. One day, when the Institute’s canteen was closed in preparation for its move to Addenbrooke’s, Jia found the cheapest place nearby to eat was at the business school. Initially drawn in by convenience, she soon discovered a plethora of events, including the Wo+Men’s Leadership Conference, the Enterprise Tuesdays lecture series and Venture Creation Weekends. And the rest is history.

Find out more at Gates Cambridge.