Evolving Origins

A former slave turned taxidermist, a governess and skilled translator, an American pioneer of women’s suffrage: Charles Darwin’s prolific correspondence – around 15,000 letters over his lifetime – reveals the rich tapestry of his global network. Through their letters to him, and his responses, Darwin’s many correspondents contributed hugely to his exploration and intellectual development. They taught him, argued with him, challenged him, shared their own work and specimens with him. But today, they are largely forgotten and unacknowledged by the wider world.

The Darwin in Conversation: Off the Page exhibition, which ran at the University Library until the end of last year, remedied this. Part of the decades-long Darwin Correspondence Project, it explored the lives and work of just a few of Darwin’s correspondents.

Posed by modern-day contemporaries, each with their own link to these histories, this photographic series reimagines those who were rarely seen and heard even less: Darwin’s own children, women, Black and Indigenous people. Each portrait draws on the wider context of Victorian society and commemorates those who were marginalised. Similarly, they also bring attention to the colonial world in which Darwin lived, worked and benefited from. Their stories have been lifted from the dusty page and brought to life, more than 150 years later: thousands more wait in silence, still to be told.

Lydia Becker

1827 – 1890

“Miss Becker presents her compliments to Mr Darwin and takes the liberty of sending him the enclosed flowers of a variety of Lychnis dioica common in the woods here but which she has not observed elsewhere.” So began the first letter to Darwin from Lydia Becker, biologist, astronomer, botanist and a leading member of the women’s suffrage movement. A Manchester native who was passionate about educating girls in science, Becker continued to correspond with Darwin between 1863 and 1877, providing him with specimens of plants and sending observations for Darwin’s work on plant dimorphism. Darwin responded to her questions, giving feedback on her writing, and advising on where best to publish her articles. In 1866, she asked him if he might send her a paper to be read at her new venture, the Manchester Ladies’ Literary Society. “A few ladies have joined together hoping for much pleasure and instruction from their little society, which is quite in its infancy and needs a helping hand.” Darwin obliged, sending not one but two papers, and Becker was delighted. “Our society appears likely to prosper beyond my expectations,” she wrote.

Sitter: Tori Blakeman, communications manager at CPI, a deep tech social enterprise headquartered in the North of England.

“Like Lydia, I want to try and make Manchester a better place for girls and women. Lydia saw the importance of sharing stories about science and used her platform to support women’s rights and women in science. I take inspiration from this – continually striving to use my privileges and platform to help create positive changes for others.”

John Edmonstone

1793 – unknown

Enslaved on a timber plantation in Demerara, British Guiana (present-day Guyana, South America), John Edmonstone was given the surname of his master, Charles. Around 1812, the plantation was visited by the naturalist Charles Waterton, who taught Edmonstone taxidermy. In 1817, Edmonstone came to Scotland with his master: as slavery was illegal on the British mainland, he became free. In 1823, he set up shop as a “bird-stuffer” at 37 Lothian Street, Edinburgh. From this shop, he taught taxidermy to students attending the nearby University of Edinburgh – including the 16-year-old Charles Darwin. Darwin paid Edmonstone a guinea per hour’s lesson every day for two months: he used these skills on his famed Beagle voyage. In notes for his unpublished autobiography, Darwin wrote: “I used often to sit with him, for he was a very pleasant and intelligent man.” It is commonly believed that Edmonstone was the “full-blooded negro with whom I happened once to be intimate” who Darwin refers to in Descent of Man as an example of how humans – no matter what their race – are all one species.

Sitter: Miranda Lowe, principal curator and museum scientist at the Natural History Museum, London, responsible for some of the specimens Charles Darwin studied as a young man.

“My connection to John Edmonstone is through cultural heritage: the art of specimen curation and taxidermy. Through my personally developed Black history tour of natural history, I have been able to bring both John and Charles’ stories together, including acknowledging John’s own contribution to science as a taxidermist.”

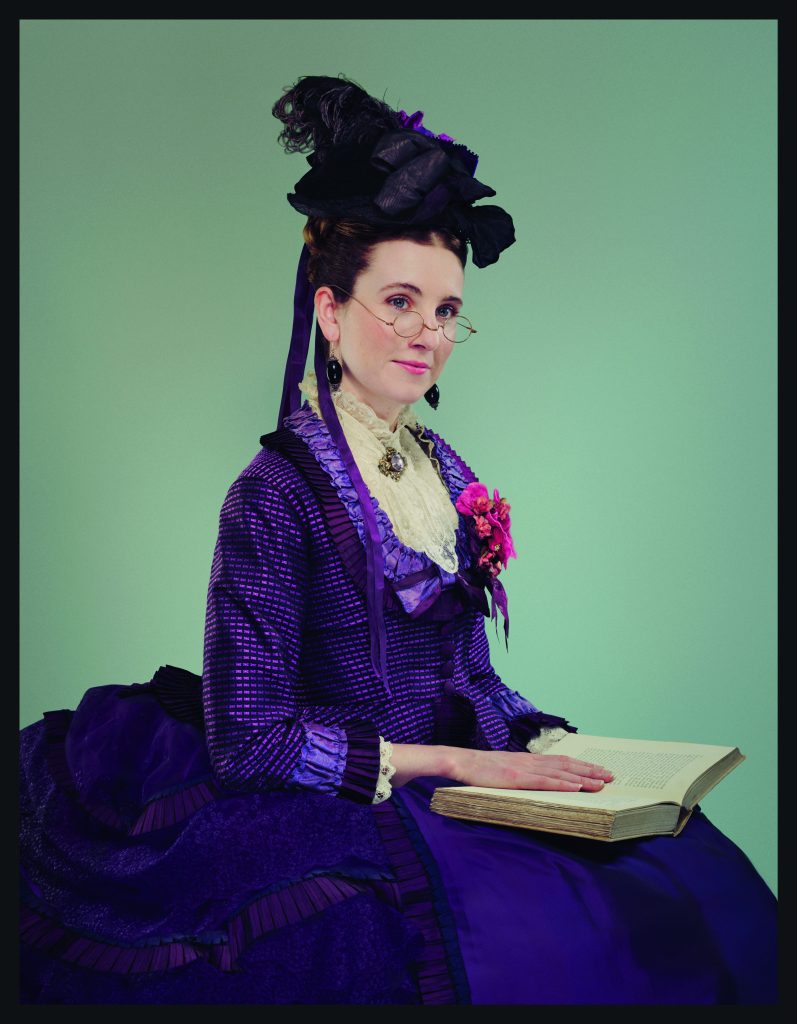

Camilla Ludwig

1837 – 1874

From 1860 to 1863, Camilla Ludwig was the Darwin children’s governess. Born in Hamburg, Camilla translated German scientific works and correspondence for Charles while with the family and after she left. His letters cover both personal matters (“Leonard travelled too soon & was injured by the journey… Horace is going on well & only occasionally has a baddish day…”) and requests for translation. Enclosing a letter from German botanist Wilhelm Pfeffer in relation to fellow botanist Julius Wiesner’s critique of Darwin’s work on plant movement, he wrote: “It is of much importance to me to know what Pfeffer means in relation to Wiesners (sic) book who has just published a book vivisecting me in the most courteous manner.” Ludwig married Reginald Saint Pattrick, vicar of Sellinge, Kent, in 1874. The Pattricks were not well-off: Charles’s wife, Emma, is known to have helped Camilla by passing on her old gowns – which is how Camilla is imagined here.

Sitter: Emma Darwin, novelist and non-fiction writer, and the great-great-granddaughter of Charles Darwin and Emma Wedgwood.

“How many layers of time and truth are sandwiched together as Leonora’s shutter clicks! This face, this curled hair and booted, corseted body is mine, but not me; Camilla, but not Camilla. And I’m wearing a gown which stands in for gowns that Great-Great-Grandmamma Emma (another me-but-not-me) passed on to Camilla.”

Christian Ngqika

1831 – unknown

In his 1872 book The Expression of the Emotions of Humans and Animals, Darwin wrote that an amateur naturalist living in South Africa, JP Manwell Weale, made “some observations on the natives and procured for me a curious document, namely, the opinion, written in English, of Christian Gaika (sic), brother of the Chief Sandilli, on the expressions of his fellow-countrymen”. This document was a questionnaire – on how emotion is expressed – that Darwin had sent out worldwide. Born in Burnshill, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa, Christian Ngqika’s father was a chief of the Xhosa tribe. Ngqika was educated by missionaries and employed by the colonial government as a constable and interpreter. Guilt, Ngquika wrote, “can be recognised by the eyes half opend, and the chin to the breast, and some times by the movements in the body. jealous by the distemper showen to the party”. And in response to the question, “Is laughter ever carried to such an extreme as to bring tears into the eyes?”, he responded: “yes that is their common practice.” His answers, written in English, are the only responses from an Indigenous person.

Sitter: Bryan Knight, journalist, oral historian and host of the Tell a Friend podcast.

“Christian Ngqika’s story deeply resonates with me, as his interpreter role mirrors that which I see for myself. In my journalism and oral history archiving, I seek to unveil the past to help communities understand themselves and the world around them.”

Mary Treat

1830 – 1923

“Mrs Treat of New Jersey has been more successful than any other observer,” Darwin wrote of naturalist Mary Treat’s investigations of carnivorous plants, which he drew on for his 1875 book, Insectivorous Plants. Born in 1830, Treat was a prolific writer and scientific investigator, publishing five books and more than 70 scientific and popular articles. Treat first wrote to Darwin in December 1871, describing her observations of fly-catching plant Drosera and her experiments with Papilio asterias butterflies. “I learned to distinguish the sex in the larva state – the female being larger than the male – and this led me to try to control the sex.” Darwin was intrigued. “I am very much obliged for your kind letter; & should esteem it a great favour if during warm weather next summer you will observe two points for me in Drosera filiformis,” he wrote. The two went on to exchange 15 letters from 1871 to 1876 – more than any other woman naturalist. A lively correspondent, unafraid to challenge Darwin’s hypotheses, Treat’s name lives on in her work and one of her discoveries – the ant named Aphanogaster treatiae in her honour.

Sitter: Dr Sandy Knapp, botanist, past president of the Linnean Society of London, author of Extraordinary Orchids and In the Name of Plants.

“I have always admired Mary Treat – as a botanist and as a woman in what was, in her time, a man’s world. Her powers of observation and analysis were at the highest level.”