The Lost Key

‘From the sublime to the ridiculous’ – Cambridge porters spill the beans.

The black bowler may be customary, but today’s College porters are called on to wear any number of hats during a day’s (and night’s) work. They might take on the role of security guard, student counsellor, postal worker, tourist guide, conference assistant, locksmith, receptionist or crime prevention officer – and even, on occasion, do a little of the heavy lifting that Cambridge outsiders might assume their job entails.

That list is not exhaustive. Weeks after joining King’s as Head Porter in 2014, former police officer Neil Seabridge found himself being measured up for a top hat. “Nobody told me I had a ceremonial role when I applied for the job,” he says. “But I was soon dressed in my number one uniform and top hat to lead the procession for the King’s Sermon, carrying a silver-topped mace that was presented to the College by one of my predecessors back in 1645.”

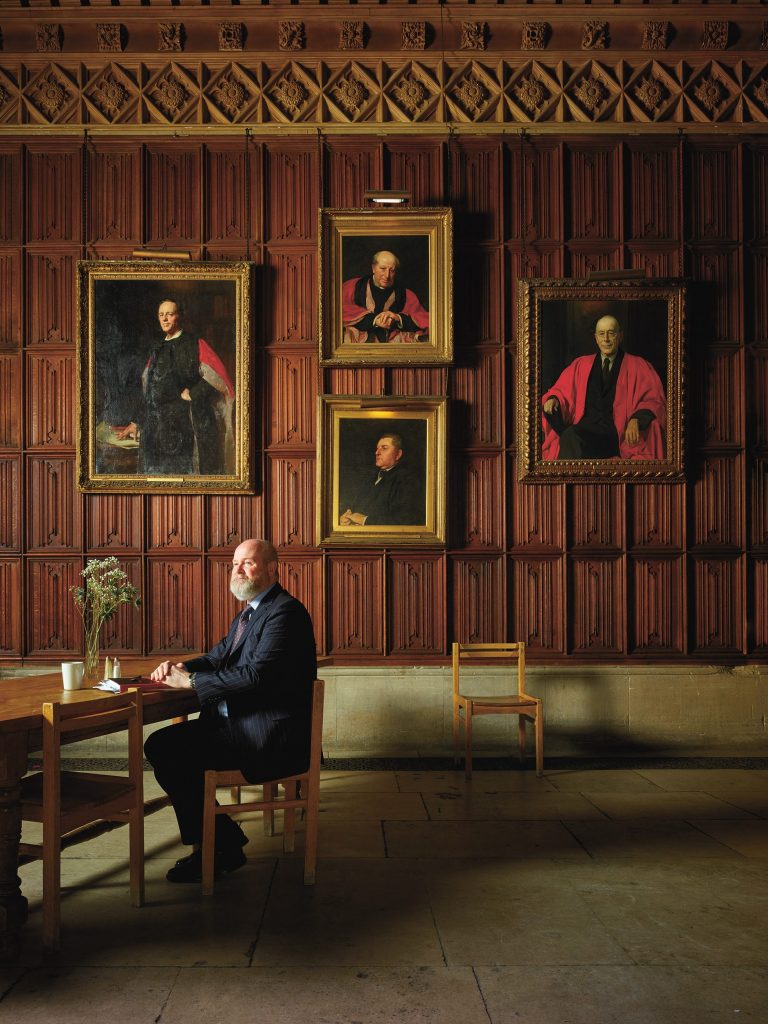

Surprises are very much part of the territory. A recent recruitment advert at Homerton specified a “reliable, committed team worker who enjoys the unexpected”. And although Head Porter, Gordon Murray, had previously served in the Household Cavalry, for the City of London Police and as John Major’s close protection officer when in Cambridgeshire, he admits that he still faces situations he has never encountered before.

He says: “Even after 30-odd years in public service, I’m never surprised at being surprised. Unexpected events spring up in all communities, and an academic place of learning is no different. Some are comical and some less so.”

“Often on a night shift, students feeling stressed will come in to chat about anything – perhaps just a TV programme or a film – and if they want to get something off their chest, they can do that.”

Sarah Hendry, Pembroke Porter

“The job runs from the sublime to the ridiculous,” says Seabridge. “It can be chasing geese off the front lawn or fishing students out of the river at 5am.

“And we get all the japes you’d expect, with traffic cones appearing in peculiar places. They always think they’re being original with their pranks, but we were pulling the same stunts when I was a student 40 years ago.” Seabridge adds.

As with so much in the University’s history, the role of porter developed in piecemeal fashion. A “keeper of the gate” is mentioned in King’s 1453 Founder’s Statute, with duties that included making torches for the Chapel, waiting on tables in hall, and having to “duly and diligently shave the Provost, Fellows, Scholars and other persons” (indeed, the roles of head porter and College barber were combined until 1861). However, Pembroke did not appoint a porter until the early 17th century, when a new court was added. Until then, gatekeeping was the responsibility of a scholar or ‘sizar’ – a poor student who acted as a part-time College servant.

Polyglot porters

By the time The Student’s Guide to the University of Cambridge was published in 1866, the role had been somewhat standardised. The book, aimed at prospective applicants, notes that a porter’s duties varied by College, but “in all cases he has to keep the gate, he has to be ready to be called up at any time of night in case of illness or any emergency, to see to the carrying of luggage, and to fetch and carry the letters to and from the post office, and to see to the lighting of the courts and staircases”. It further notes that undergraduates had to pay between five and 10 shillings a term for these services, plus one halfpenny for each letter received. With five mail deliveries a day, this must have added up to a significant income for the porter and his assistants.

For much of the 20th century, middle-aged retirees from the police and armed forces formed the backbone of the University’s cadre of porters. Some Colleges would always seek to recruit from particular regiments; in others, a handful of families supplied generations of porters and other College staff, with plum roles passing down from father to son.

A lost key often signifies more than a lost key: students might have an ulterior motive

While these traditional backgrounds are still well represented, most lodges are gradually becoming as cosmopolitan as the body of students they watch over. “At King’s we’ve got two other retired police officers, a former railway worker, an estate agent and a chap who had his own design company,” Seabridge says. “One of my porters has a PhD in Chemistry and had a former career as a research chemist at ICI, and among the relief porters is one of our ex-graduate students, who left with a Classics degree.

“We did a tally the other day of the languages spoken in the lodge. We have English, French, Estonian, Russian, Swedish, Classical Latin and Greek, Italian and Spanish, a smattering of Danish and Norwegian… It all illustrates the varied experience they can bring to the College.”

Even at the turn of the millennium, the job was overwhelmingly a male preserve. It was not until 2009 that Helen Stephens became the first woman to take charge of a Cambridge porters’ lodge, joining Selwyn after spells as Deputy Head Porter at Trinity and the first female porter at Jesus College. She says: “I still ask myself why it took 800 years, when women have been at the forefront of the University for a long time. But I just applied for the job and was fortunate to be given the chance.”

The open door

Cheryl Bowran, who was appointed Head Porter at Newnham College after 14 years as a senior prison officer, says: “Having a female head porter is still quite a novel idea for some people, and you do get some comments. But I take it in my stride – I know I’m here because I have the skills and ability to do the job.”

She admits that her previous career is the subject of occasional ribbing from the students. But while wielding keys and regulating access might be the most conspicuous aspects of both jobs, for around 40 years Colleges have differed from prisons in allowing inmates to come and go as they please. “No College should be a fortress,” says Murray. “But safety and security are paramount. You just have to be proportionate.”

CCTV and electronic locks have made the task somewhat easier, but some Colleges present a special challenge. King’s attracts more than 350,000 visitors a year, and is a much-used thoroughfare for University members travelling between town and the Sidgwick Site. “The College wants to be welcoming,” Seabridge says, “but we have to apply basic security measures to allow that spirit of openness to continue. It’s good that students feel safe in the King’s environment, but the bad news is that they drop their guard. They’ll leave iPhones lying around, or leave their front doors open. That absence of self-protection sometimes surprises me, so I have to keep encouraging them to take responsibility.”

You get to watch them grow and turn into a young adult over three years. That’s the part I enjoy the most.

Sarah Hendry, who spent 25 years in retail before becoming a porter at Pembroke, agrees. “Students can definitely get too comfortable, probably because it’s their first time away from home,” she says. “Within weeks of the new freshers coming in, we go round checking doors. If they’ve gone away and left their doors open, we lock them out!”

Asked how the job has changed over recent years, many porters report that the pastoral side of the role has increasingly come to the fore – something driven by greater awareness of welfare issues. “My number one priority is the students,” says Hendry. “They’re under my duty of care while they’re at College. Often on a night shift, students will just come in for a chat. They want to have a rant because they’re feeling stressed, so we’ll chat about anything – perhaps just a TV programme or a film – and if they want to get something off their chest, they can do that.

“However, there are times when you’ll see a student’s pattern of behaviour change, and you’ll have a word with the Tutorial Office, the Dean or the nurse. More often than not, you’ll find that it has been noted already.”

Sounding boards

A maxim that rookie porters learn early on is that a lost key often signifies more than a lost key: students might have an ulterior motive for showing up at the lodge. “That sort of thing does happen a lot,” says Bowran. “They come to see us with reasons that seem a little specious, and they might actually need a friendly chat, or a bit of support with something. We are often good sounding boards.”

“During exam term, the porters go out and buy sweets. There’s always a big bowl of them on the front desk that we encourage the students to take. It’s a way of giving them an excuse to see us, and letting them know there’s someone who cares. If need be, we can say, ‘You’re a bit quiet nowadays. Is everything all right?’”

Most Colleges now provide mental health training for porters so they can recognise and deal with acute problems and know when to seek further help. Stephens says: “We see a side of the students that is not always visible to their academic contacts, and it’s a good thing that mental health is being talked about far more openly. We’re lucky at Selwyn, as the College has invested heavily in training me and my team and supporting our members: later this year we will be doing a two-day course on mental health first aid.”

But as well as looking after junior members, porters are charged with enforcing discipline. When College rules are broken, the two sides of the pastoral role must be balanced; and this can present one of the job’s thorniest challenges. “It may sound a bit trite, but I rely on the three Fs: be firm, fair and friendly,” says Seabridge. “You need to beef up the firmness in some exchanges, but you should still be fair and friendly.”

Miscreant students (and sometimes staff and fellows) would do well to remember that honesty is the best policy when dealing with porters. “Remember, there’s nothing secret in a College,” says Hendry. “Someone always talks. So you’re far better off coming to say, ‘Yes, it was me – I broke the door. I was drunk and stupid.’ It’s a lot more painless to go to the senior tutor off your own back, rather than be reported by the porters’ lodge. I’m not the biggest disciplinarian in the world and I’ll always give people the benefit of the doubt. But if someone’s a repeat offender… well, there’s nothing worse than the wrath of an angry porter!”

So what attributes are needed to succeed at the job? A good level of intellect is the first requirement, according to Murray. “You don’t need to be academic, but a lot of the day-to-day tasks are now computer-based, and they’re always changing and modernising. Above all, you need to be a great listener, not just a good one. If you just sit and nod, you may not pick up on some of the things that a student is trying to express to you. You have to ensure that every one of them feels part of the College and no one is excluded.” Bowran says: “It demands a lot of common sense and the ability to think on your feet. We get all sorts of bizarre situations all the time that you can’t prepare for. And you have to be a practical person to deal with door locks and broken bikes.”

All agree that it is a career unlike any other, with a unique set of rewards. But one form of job satisfaction gets a particular mention. “You see this fresh-faced student come in looking like a rabbit in the headlights,” says Hendry, “and you get to watch them grow and turn into a young adult over three years. That’s the part I enjoy the most.” Murray agrees. He says:

“It’s a real privilege to go with the Praelectors and Senior Tutor at the head of the procession to the Senate House, to hand the students over to the University and see them receive their degrees. That’s a sheer delight.”