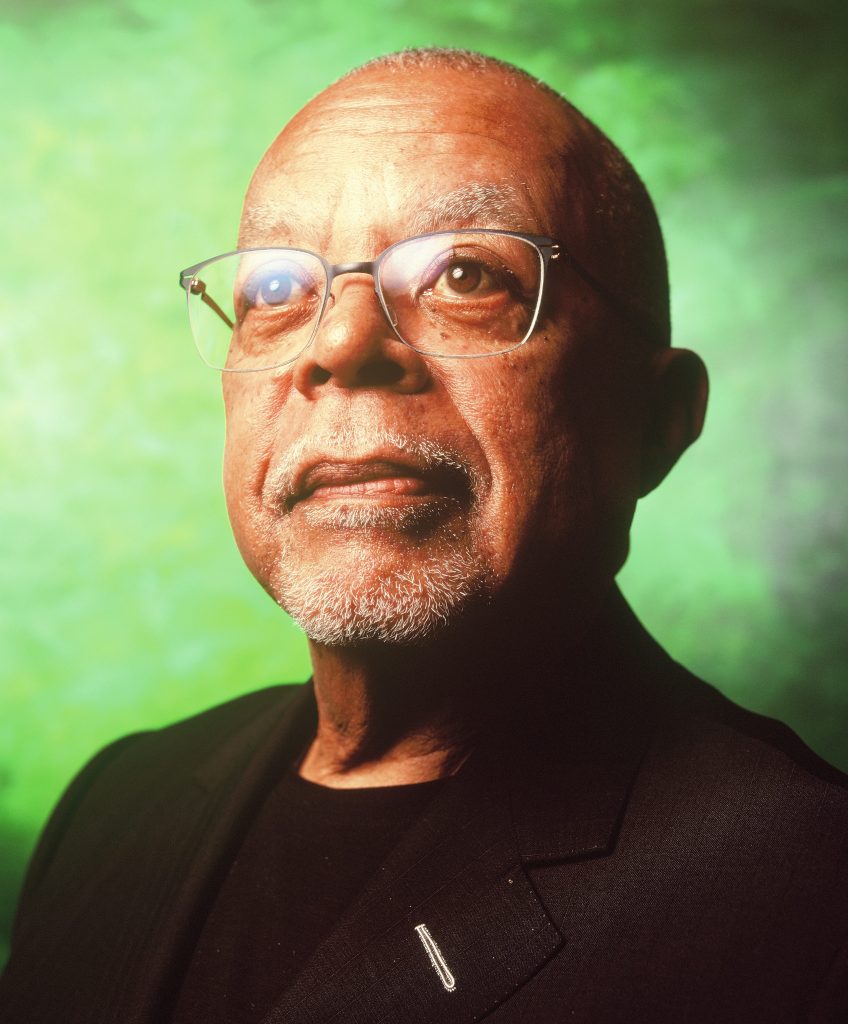

Henry Louis Gates Jr (Clare 1973) has changed the way “Black authors get read and Black history gets told”

Without Henry Louis Gates Jr (Clare 1973), the field of African and African-American literature studies would look significantly – significantly – different. This son of an education-conscious working-class family from Piedmont, West Virginia has become one of the world’s leading African-American academics, “changing the way Black authors get read and the way Black history gets told”, as the New Yorker put it.

It could all have been so different. After his sophomore year at Yale, as part of the university’s experimental “five-year BA” programme, and intending to study medicine, Gates took a gap year to work at an Anglican Mission hospital in Tanzania, which changed his life. His journey to Tanzania took him around Europe, the Holy Land and two stops before Dar es Salaam. On the way home, Gates and a recent Harvard graduate spent two months hitchhiking across the equator, from Dar to Kinshasa, Congo, before flying on to Accra, Ghana, “on a pilgrimage to the grave of WEB Du Bois – every Black intellectual’s hero”. It was, he reflects, “a profoundly maturing experience”.

After studying History at Yale, he became the first African-American to get a PhD (in English Literature) from Cambridge.

After studying History at Yale, he became the first African-American to get a PhD (in English Literature) from Cambridge. “The cliché was that extraordinary people went to Harvard, Yale and Princeton and to Oxford or Cambridge. That was the fantasy. I got into Yale, did very well academically and applied for six fellowships – and though a finalist, was turned down for all of them, including the Rhodes and Fulbright. A very kind Dean suggested I apply for a Mellon (an Andrew W Mellon Foundation Fellowship) at Cambridge and, to my amazement, I was accepted. Fantasy fulfilled.”

When he entered Clare in 1973, studying African or African-American literature was not an option. “It wasn’t seen as literature, but as a study in social anthropology.” Noted social anthropologist Professor Jack Goody directed him to Wole Soyinka [the sole professor in the subject, a visiting fellow at Churchill College, in exile from his home country of Nigeria]. “I wrote to him, he wrote back, we met, and he agreed to spend the year supervising me in African mythology and literature. I was his only student. The rest is history.”

Life at Cambridge was not without its pain and stresses, however. “The fact that Wole Soyinka was denied affiliation with the English faculty at that time left a bad taste – it meant that African literature was not regarded as proper field of study. I wanted to write my thesis about a Black author and was told I couldn’t.” The thesis he did write is about ideas of race in the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment, and the significance of individual Africans publishing books in Europe to the debate about the African’s ‘place in nature’. “My thesis blossomed into studying the relationship between race and reason, and writing, and what all of this had to do with the Africans’ place on the great chain of being.”

When I began teaching, I advocated close reading of Black literature as literature, not as biography or anthropology or sociology.

His Cambridge education also introduced him to practical criticism, “a distinctly Cantabrigian way of reading. To this day, it’s how I read literature. When I began teaching, I advocated close reading of Black literature as literature, not as biography or anthropology or sociology. And I wasn’t the only one – this method of explicating texts struck a nerve and became part of a widespread effort to institutionalise the field of African-American and African literature in English departments as literature, first and foremost.”

His life since has been an extraordinary and pioneering journey, with other noted contemporaries such as his Clare College contemporary, Kwame Anthony Appiah (1972), to establish the fields of African and African-American Studies as fully fledged academic departments, with the right to grant tenure and award PhDs. The department that he and Appiah embarked on rebuilding at Harvard in 1991 has more than 40 faculty members, the largest African languages programme in the world, and has turned out dozens of PhDs. He has taught African and African-American literature at Cornell, Duke and Harvard, but began his career at Yale, where he became co-director of the Black Periodical Literature Project, and earned a reputation as a ‘literary archaeologist’ for authenticating the first novel published by an African-American female author, Our Nig, by Harriet E Wilson (1859). More recently, he authenticated the manuscript of The Bondwoman’s Narrative, by Hannah Crafts, a novel written before Wilson’s book but never published. In recent years, he has been a prolific filmmaker, mainly for the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) and HBO. His popular PBS series, Finding Your Roots, is about to air its 10th season.

One of his greatest sources of pride, however, remains his honorary degree from Cambridge and Fellowship at Clare.

One of his greatest sources of pride, however, remains his honorary degree from Cambridge and Fellowship at Clare. “I almost cried when I received the Vice-Chancellor’s letter in 2020,” he says. “I was astonished.” The ceremony was delayed until 2022 when he received his degree along with his mentor, Wole Soyinka, now Professor Emeritus, Dramatic Literature of the Obafemi Awolowo University, and old friend from Cambridge, Professor Kwame Anthony Appiah, who teaches Philosophy and Law at New York University, both of whom Gates describes as “his oldest and closest friends”.

“I was extremely fortunate to live in Africa when I was 20, to graduate with the highest honours from Yale, and then to attend Clare. These experiences introduced me to the concept of ‘race’ in a completely new way. It made me approach race in a more sophisticated way – in its relationship to class, for instance – and internationalised my understanding of the Black experience throughout the world. My debt to the University of Cambridge will be difficult to repay.”

-

Portrait of Henry Louis Gates Jr at the Fitzwilliam Museum

This year, the world-renowned American artist Kerry James Marshall, whose work questions the social constructs of beauty, taste and power, donated his portrait of Henry Louis Gates Jr to the Fitzwilliam. The portrait is now on display outside the museum’s Black Atlantic exhibition.

Henry Louis Gates Jr is an Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker, literary scholar, journalist, cultural critic and institution builder. He is also the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and the Director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research at Harvard University.