From Cambridge to Kyiv: the economics of war and recovery

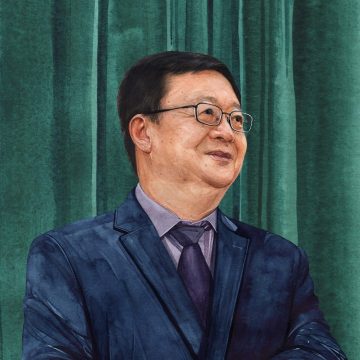

Dr Alexander Rodnyansky, Assistant Professor of Economics in the Faculty of Economics, spoke to CAM in September 2022 from Ukraine, where he has been based since the start of the war.

I’ve been President Zelensky’s economic adviser since 2019. Alongside my work in Cambridge, I sat on the supervisory board of a major bank and provided input on all kinds of financial, macro-economic and fiscal topics. I was used to advising on economics in a relatively stable environment. But that all changed in February.

On day one of the war, everything became very chaotic. Like many others, I suddenly found myself dealing with issues that went way beyond my expertise – arms, supplies, military matters, the media and sanctions. But I knew immediately it would be disastrous for our economy.

Months later, we saw that devastation play out. The forecast was for a GDP contraction of 50 per cent in the worst-case scenario and 35 per cent in the best – so we expect something in the middle. That is a full-blown disaster: many would say you do not even have to reach those numbers for a disaster to be happening. And it reflects, of course, what is happening in our country: business and activity across the whole country is suffering from the uncertainty that comes from the consequences of war.

It became very chaotic. I found myself dealing with issues that went way beyond my expertise – arms, supplies, military matters, the media

It’s harder to predict what will happen six months from now. At the moment, Ukraine is not investable, and it’s difficult to envisage any standard mechanisms through which investment could work. Our capital flows are limited because we don’t want our currency to collapse. We need to provide some kind of macroeconomic stability – as much as we can. But we are running a huge budget deficit. Our tax revenues have collapsed and the economy is shrinking, but at the same time, government expenditure has gone up by four or five times for the military sector.

With a huge deficit and a fixed exchange rate – essential if we are to avoid huge volatility – we are on the brink of a first-generation currency crisis. But there is no easy way out. Financial aid from our western partners is happening, but it’s slow and fraught with political hurdles. It is not covering our deficit, so we are accumulating a lot of very expensive debt. Our final, worst option is to monetise the debt: in other words, print more money. That will cause inflation. If inflation skyrockets, we really will have lost all macroeconomic stability.

But we have seen progress. In normal times, exports make up around 45 per cent of our GDP. All the problems I’m describing come from the blockade: it deprives us of the exporting capacity that would otherwise be putting dollars in our reserves, helping us to stabilise our currency. But the opening up of ship routes is a positive development.

Economists have a role to play in wartime, and I’ve been able to use some of my expertise for the benefit of the country.

Economists have a role to play in wartime, and I’ve been able to use some of my expertise for the benefit of the country. But luckily, a lot of these decisions are still made correctly without having economic expertise to back them up. Many times, I’ve observed our president asking the relevant economic questions without the help of an economics professor. Economics provides discipline. It models reality and thinks about how the world and people function. But you don’t have to know what a first-generation currency crisis is to figure out that you need more reserves.

We continue to live with uncertainty. I have been very vocal in our Sanctions Group: most of those that have been introduced will play out over time and have a medium-term effect before they start to properly bite. Importantly, we need to limit Russia’s ability to export – primarily oil and gas. There is currently a lot of circumvention going on, which is an ongoing concern: Russia’s budget revenues are 50 to 60 per cent reliant on energy sales. Personal target sanctions are another tool. They might not stop the war but they could play a part in destabilising the regime, and try to make sure that Russia transitions from this autocratic equilibrium to something that’s more democratic.

But we are also looking to the future and to recovery – as much as we can, when any building back could be destroyed immediately. For now, we are deeply grateful for the support we have received from the UK, and from the University: long may it continue.