Democracy is back. And thank goodness – because in challenging times we need more, not less, of it

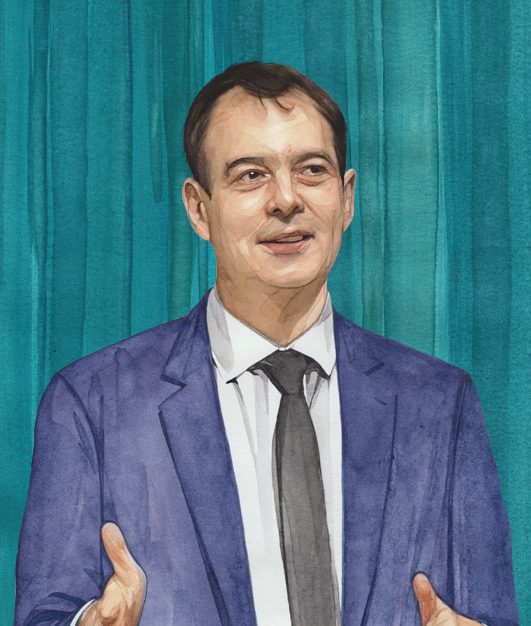

Professor of Politics David Runciman, on why democracy will be back.

Remember democracy? Just six months ago the UK was full of it. We had a hotly contested general election along with furious argument – inside and outside parliament – about Brexit. Extinction Rebellion brought the politics of civil disobedience to the streets. There was an atmosphere of conflict and dissent. Disagreement was everywhere.

Today that seems like another age. Party divisions are stifled, experts are heeded and the atmosphere is one of baffled deference to authority. Parliament is a shadow of its former self. A fractured political society has been brought together by the experience of a common threat.

But I would argue that we should beware those who predict a permanent change. Contentious democracy will soon be back. Why? Because nothing about the political response to the pandemic has altered the forces that were driving growing democratic dissent. People were increasingly frustrated with representative institutions that many felt no longer spoke for them. This in turn reflected a growing sense that parts of the economy were being left behind and parts of society were being ignored.

Over the next few years, governments everywhere will have to make tough choices about who continues to get economic help and who is left to fend for themselves. There will be winners and losers. For now, with many of us still confined to our homes, we have all been getting the same message from the government. Soon we will start answering back. Under conditions of economic hardship, these arguments are likely to be even more ferocious.

At the same time, new technology is continuing to amplify our disagreements. The same platforms that give governments the ability to track our movements also give citizens the ability to voice their fury. The digital revolution has always pulled politics in both directions at once: towards more control and towards more contestation. The pandemic doesn’t change that.

The social divides that have recently opened up in democratic politics are likely to widen over the coming years. The Brexit referendum revealed a nation deeply split by age and education. It was old vs young, graduates vs non-graduates. The economic fallout of the lockdown will do nothing to diminish these divisions. Educational and generational inequalities are being exacerbated. For now, many young people are happy to make sacrifices for the sake of older people. But, over time, they will want something in return. If they don’t get it, anger will grow.

My feeling is that the Brexit years were just a warm-up for the political fights coming, which will be starker, because the stakes will be higher. In some ways, this should not worry us. It means that fears of a slide into authoritarianism are probably overblown. First, because authoritarian regimes are going to be facing the same pressures. And, second, because democratic publics are going to resist being pushed around. We won’t find it hard to recognise we still live in a democracy.

The danger is that we try to deal with these challenges without reforming the institutions that have left so many people feeling ignored. What the past few years have shown is how hard it is to manage contentious democracy through traditional forms of democratic politics. Representative democracy was under strain because more and more voters wanted a direct say in the decisions that affected their lives. New forms of technology made that seem possible. Old systems of democracy made it seem futile.

The present crisis is an opportunity to try something new in our politics. We should not be afraid of deep democratic disagreement. But we should be wary of trying to manage that disagreement while stifling greater opportunities for political participation. More direct democracy, more local democracy, more workplace democracy, more deliberative democracy would all offer something different.

Democracy will only be the loser from this crisis if we think it can somehow stay the same when the world has changed.

David Runciman is Professor of Politics and the host of the Talking Politics podcast.