City of refuge

From London students escaping the Blitz to Ukrainian students fleeing the Russian invasion, Cambridge has long offered a place of safety.

October 1944. A young Thelma Prideaux Coyte, Honours Physics student at Queen Mary’s College (QMC) in London, is making the long journey from her hometown of Plymouth to meet the Head of Physics at Cambridge. Carrying little more than her ration book and two small dishes for butter and jam – her bicycle and trunk having been sent ahead – she is keen to get stuck into her studies, the latest in a large collection of students evacuated from the University of London as part of the war effort.

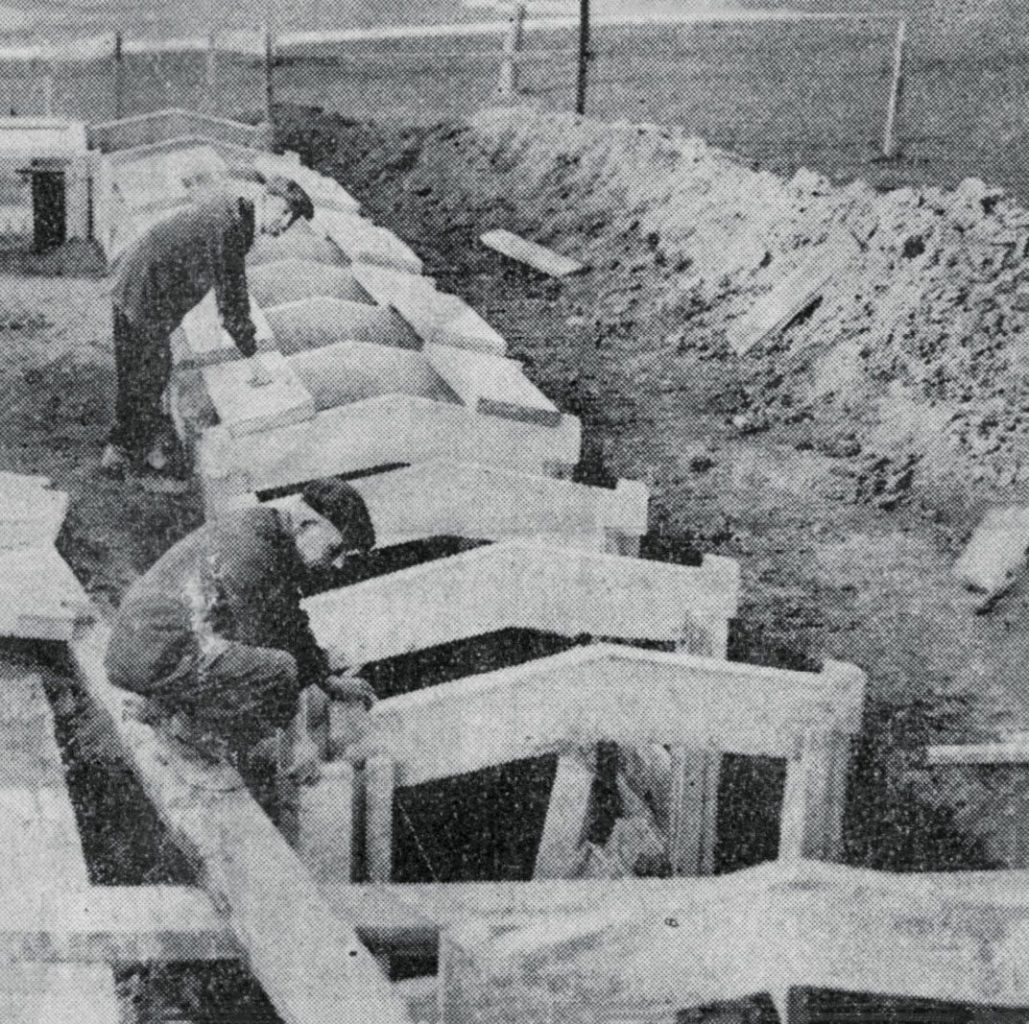

“The first sight of the city, and of King’s in particular where we would be attached, was breathtaking. But the meeting with the head of department was a little baffling, as he seemed keen for me to read Botany instead. I stuck with Physics, though – I was just advised to keep a low profile for a while – and was delighted to find the lectures were fascinating: highly entertaining with spectacular demonstrations – but a lack of supporting theory. We presumed that the Cambridge students got their theory in tutorials, but QMC students didn’t have tutorials so our lecturers were more thorough over theory – but far less fun!!”

“The first sight of the city, and of King’s in particular where we would be attached, was breathtaking. But the meeting with the head of department was a little baffling, as he seemed keen for me to read Botany instead. I stuck with Physics”

Thelma Coyte (who would become Thelma Butland by marriage) was just one of the thousands (estimates vary from 5,000 to 10,000, owing to some double counting) of London students evacuated to Cambridge during the war, largely to free up buildings for government use rather than protect individuals from the bombing. In all, seven London colleges were involved: King’s hosted QMC students, St Catharine’s became home to students from the Bartlett School of Architecture and The London Hospital Medical College, while the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) went to Christ’s, the London School of Economics (LSE) to Peterhouse, Bedford College to Newnham, and St Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College (Barts) to Queens’.

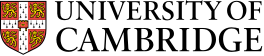

The process had actually begun in 1939, part of a planned wider dispersal of the University of London agreed between the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principals (CVCP) and the Chamberlain government. At the outset of the war, LSE was required to vacate its central London site in a hurry to make way for the Ministry of Works. Alarmed at the government’s suggestion of a move to distant Scotland, the director of LSE, Alexander Carr-Saunders, and the Master of Peterhouse, Paul Vellacott, informally agreed that LSE would rent Grove Lodge from the College to provide facilities for the evacuated students.

“The students of Girton and Newnham return to Cambridge this term only to discover that the inequality of the sexes under which they have long been accustomed to profit is now almost annihilated by an influx of females from the University of London”

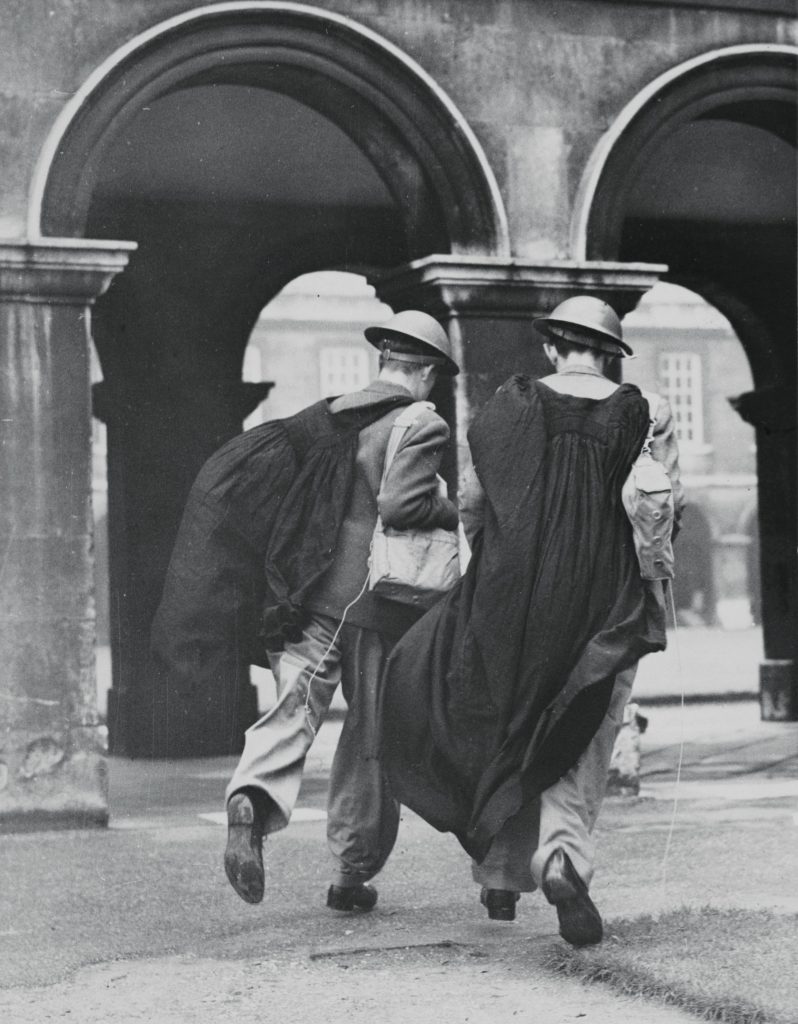

Eyebrows were raised. Cambridge’s oldest College (Peterhouse was founded in 1284) was all-male, largely British and notoriously conservative, while the student population of LSE in 1939 was 68 per cent female and with many immigrants among staff and students, nearly a quarter of the latter coming from overseas.

“I mean, why would you do it?” asks Professor Tony Watts OBE, a Fellow Commoner at St Catharine’s. “Send a large, leftie, predominantly female group of students to Cambridge’s smallest, most reactionary College? Yet it turned out to be one of the most successful relationships of the London colleges that moved to Cambridge during the war.”

The arrival of the London students significantly altered the gender balance of the student body in Cambridge, not always to the delight of the women already studying there. A female Cambridge student wrote in 1939: “The students of Girton and Newnham return to Cambridge this term only to discover that the inequality of the sexes under which they have long been accustomed to profit is now almost annihilated by an influx of females from the University of London.”

And the presence of female academic staff caused consternation at some Colleges, Watts notes. “Christ’s made male members of the SOAS teaching staff members of High Table, as long as no more than six dined on any one night, whereas female members of the SOAS academic staff were offered lunch in Hall but not dinner.” They were, however, joined at lunch by their female students – for the first time in the College’s history.

Women students coming from mixed London colleges now paired with all-male Cambridge colleges were generally billeted into lodgings, whereas male students were generally accommodated on site. As Thelma Coyte remembers: “The era of mixed colleges had not yet reached Cambridge. The many empty rooms in King’s were occupied by male students of QMC. Of course, no women students were allowed rooms there. So we were found accommodation in various houses in the city.”

In fact, pressure on accommodation in Cambridge was very tight. One of the leading economists of the time, LSE’s Friedrich von Hayek (later regarded as Margaret Thatcher’s guru) was grateful to his academic opposite John Maynard Keynes for helping him find accommodation at King’s, with Keynes also finding Hayek’s son Laurence a place at King’s College School. Hayek and Keynes regularly shared the night watch for fires from the College roofs (oh to be a fly on the wall for those conversations), and Hayek was later to report that the hospitality shown to him and his fellow teachers from LSE was one of his pleasantest memories of the war.

Not that this was entirely unprecedented: Cambridge was already known as a sanctuary for persecuted academics from fascist Europe from as early as 1933, according to Dr Theodor Dunkelgrün, affiliated lecturer in the Faculty of History.

Among the many distinguished academics, as his former student Professor Rosamond McKitterick told a 2020 international conference co-organised by Dunkelgrün, was the medieval historian and criminal lawyer Walter Ullmann, forced to flee his native Austria due to his prosecution of Nazi criminals, and the fact that he had one Jewish grandparent.

Ullmann escaped to England in 1938 thanks to a Cambridge committee for the support of refugee scholars, and found his home at Trinity College, where he remained until his death in 1983. Ullmann’s fellow Austrian, the molecular biologist Max Ferdinand Perutz, arrived at the Cavendish Laboratory in 1936 to work in the field of X-ray crystallography. Having completed his PhD, his research was interrupted by the outbreak of the war when, alongside hundreds of others, he was interned as an ‘enemy alien’ and sent to Canada. Following extensive efforts by other Cambridge scientists and the Royal Society, Perutz arrived back in Cambridge in January 1941.

“Many a Bart’s man will be heard in the future to tell his grandchildren that he did his physics in the great Cavendish laboratory”

On his return, Perutz found himself studying alongside the evacuated London students and staff. Sir Lawrence Bragg, then Head of the Cavendish Physics Laboratory, remarked that he would not have been able to keep the Cavendish open without the help of the QMC Physics Department. The St Bartholomew’s Hospital Journal War Bulletin of 1941, meanwhile, noted that “many a Bart’s man will be heard in the future to tell his grandchildren that he did his physics in the great Cavendish laboratory”.

Historian Norman Longmate describes Cambridge as the great academic host of the war, but the University also benefited – not least by avoiding the empty rooms that had seriously impacted the finances of colleges in Oxford and Cambridge during the First World War. New subjects were introduced to Cambridge students, including Sociology (although the first Cambridge Professor of Sociology would not be appointed until 1970). And for the first time, the Colleges were forced to explore options for accommodating female students alongside male ones.

By 1943, the government, which had previously advised against the return of the London colleges, decided to take a neutral stance on the matter. The London Hospital Medical College returned that summer, and Bedford a year later. The Bartlett, QMC and LSE remained in Cambridge until the summer of 1945, affording Thelma Coyte the chance to fully enjoy her surroundings.

“During wartime, bonfires to celebrate November 5th were forbidden,” she says. “But by November 1944, the progress of allied forces through Europe was well established, and fear of bombing raids in Britain was very low. So, when a large bonfire was constructed in Market Square on November 5th the authorities turned a blind eye. My friends and I decided to go and see the fun. A large crowd gathered round the Market Square, the bonfire was lit, and the police stood quietly in the background.

“A few fireworks were set off, and all was orderly until after 9pm when a group of students – who were rather too merry – lifted a nearby small, parked car and attempted to add it to the bonfire. The police jumped into action, and we decided the moment had come to leave!”

Bart’s students, whose buildings had suffered severe bomb damage, did not move back to London until 1946, and while all staff and students were happy to return, for many of the evacuated students their time at Cambridge remained a treasured moment. As wartime LSE student Joan Abse put it: “Cambridge was a delightful oasis of happiness and fulfilment in a world bent on destruction.”

Helping Kharkiv medical students to continue their studies in Cambridge

Medical student Zaur Badalov was asleep at the hospital in his hometown of Kharkiv the night the Russian invasion of Ukraine began. “I was the first one to notice the windows shaking and woke the others. We were all in shock, and then that morning we had injured people coming into the hospital needing help.”

After a few weeks, Badalov moved, with his family, to the west of Ukraine, where he was able to continue his studies online while helping treat injured people arriving at local hospitals from the east. “I learned a lot helping with the cases and seeing how the doctors treated people.”

Last summer, along with 19 other medics, Badalov was offered a seven-week clinical placement at Cambridge, part of a programme to allow medical students whose training had been interrupted by the war to continue to develop their practical skills, generously funded by donations. Paul Wilkinson, Clinical Dean of the University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, initiated the twinning programme with Kharkiv National Medical University as part of the Cambridge University Help for Ukraine support package.

“Some of the Ukrainian students’ stories have been heartbreaking, but it has been great to see their positive outlook and hopes for the future. It has been wonderful seeing their hard work and determination to use this opportunity to improve their clinical skills.”

Badalov, 22, certainly made the most of his time at Cambridge. “I had a big opportunity to learn new treatment methods and take this knowledge and these skills back to Ukraine and pass it on to others.”

City of Refuge: Evacuation of University of London Colleges to Cambridge during the Second World War by A. G. Watts will be published in History of Universities, 36 (1), 2023.